In honor of Women’s History Month, we had a discussion on some of the common subjects of gender disparity in the life sciences with Dr. Sashka Dimitrievska. Sashka is the Global Therapeutic Area Head for Clinical Insights Information Practice Oncology at AstraZeneca, and has a storied and long career in the life sciences, both within academia and industry.

PF: It is a pleasure to have you with us today, Dr. Dimitrievska. You have a very extensive background across multiple areas of science – from biomedical engineering and other more academic fields, to business development and now your current position as a department head for Oncology Clinical insights in AstraZeneca, your journey in science has touched upon a breadth of subject matters. What would you say have been some highlights and common drivers of your careers?

SD: My unusually scenic career has taught me to, above all, dare. Drastic change, such as leaving academia, for the corporate world is always frightening. But change is what has underpinned my entire life – it is my one constant. This taught me to stop my innate fear of change from getting in the way of success. As I look back on my journey, I now cherish the lessons my many obstacles bequeathed to me. As to the second part of your question, my career driver would be creation. Creation – and innovation – has fueled my ability to drive forward even when the path was not simple. I have always deliberately pivoted to roles where I could create and build the unseen and, often, controversial. It may sound counterintuitive, as the academic world is traditionally the part of science that usually embraces imagination. But I have discovered an ability to be creative in the corporate world – even though large corporations thrive on structure, there is always a need for innovation. This is even more true in challenging, unsolved fields, such as oncology.

PF: Science, much like other fields, has historically been less accessible to women than men. From your own personal experiences, have you faced any struggles that you think male peers may not have had to encounter – and how do you feel the situation has changed since the beginning of your career?

SD: My own narrative has always been to focus only on what is in my control. Even now in my department I encourage everyone to assess only the aspect that we can actually impact.

Admittedly, I often walked into rooms as the only woman, and often the only immigrant in the room. But this was not something I could change; unsurprisingly, I faced many biases and prejudice. I persevered, concentrating on what was within my own abilities and control: I prepared, and made sure to work as hard as I could. I did not doubt my own worth – but I wanted to prove to those who doubted me – and the people I represent – that we deserve a spot. In an ideal world, we would not have to do this. But we do not live in that ideal world yet. I still see this disparity today among my colleagues. Often, women will not even consider taking the next step up until they meet its requirements to the letter; whereas men may apply for the same promotion with fewer qualifications.

PF: In other fields, reports show that more gender diverse management and boards lead to more successful companies. In science, studies have shown that gender diverse, but also ethnically diverse, authorship teams publish papers that receive more citations than less diverse authors. Clearly, the inclusion of well-rounded perspectives is an overall positive – and opens up a bigger percentage of the workforce to the recruitment pool. Has this been your experience as well? What do you feel needs to be done to encourage greater diversity?

SD: I wholeheartedly agree and embrace these findings – I am very passionate about this topic. I currently co-chair the AstraZeneca Inclusion & Diversity Oncology committee, where I push the diversity definition to include often unseen, or invisible, diversities. These include thinking styles, values, disabilities – which often go unnoticed. I strongly believe their inclusion can add tremendous strength to not just mine but all global departments through promoting more points of view. After all, our market is diverse – how can we be in tune with it if we do not try to reflect that diversity? I must admit I do not have the singular answer of how to better proactively recruit diverse talent. There is a reason this remains challenging across different industries – it is a multifaceted, structural and societal problem that will take great collective efforts to solve. Still, I have seen and felt a difference by simply creating a safe environment to acknowledge and celebrate our visible and invisible diversities. I have seen how the inclusion of multiple backgrounds and various other characteristics, such as learning disabilities, can build a more cohesive department.

PF: The early stages of a career in research – particularly at the postgraduate and postdoctoral levels – involve grueling hours, low compensation, and require immense dedication. A chronic obstacle to inclusion has been a question every woman dreads: “How will you reconcile these career demands with “family life”?”. Men rarely have to answer this question. Do you feel science, and society at large, are becoming more accommodating to the more even distribution of work and family duties across genders?

SD: For me, this question is quite personal – and one I have pondered a lot as a biopharma executive that has to balance my career with a young child. In graduate school, it was often taken for granted that women were delaying children until our final year of postgraduate studies. This was not only in response to the high cost considerations of having children, but also the physical demands of some of our graduate programs. Given postgraduate training programs have an end date in sight, this felt like a manageable status quo. However in the corporate world I am witnessing a very trying dichotomy – especially at our more senior roles. Whilst our career is a cornerstone to our world and who we are as women – many women still delay moving onto the next career level out of fear of family responsibilities. This deliberately delayed progression in the interest of family is not something I encounter with men. Obviously we have moved on to being more considerate of family needs and balancing them with careers as an industry, but there remain gaps to be bridged between men and women. I think countries with maternity and paternity leaves are sending out the right signals regarding the more even distribution of family duties across the world. But there is more we can all do to ensure that women are not unfairly burdened with all the family expectations – and that men make sure to pick up some of the slack in that department.

PF: The entrenched position of men in dominating STEM fields – even more so for the physical sciences than the life sciences – is often cited as one of the main obstacles for gender inclusivity in science. This results in fewer role models that young women can identify with and look up to in the field. What would you say were some of your own role models when considering a life in science, and how did they inspire you?

SD: I am blessed to be raised by an ambitious psychologist mother whom I looked up to as my role model. My mom made this inspiration very easy as she asymmetrically shouldered our nuclear family’s financial and emotional burden. She did this while remaining true to her ethically demanding standards on gender equality – probably steaming from the 60’s of her youth! Because of my mother’s concerted efforts to raise my brother and I in a gender neutral way, I discovered gender disparities very late in life as I entered the workforce. My adult coping mechanism mirrored my childhood, to be fair. I tried to find a successful female mentor close to me in my daily routine, who also was related in my day to day work – this ended up being Laura Niklason. It was helpful to look up to trailblazing women – and I think there is a wide array of already famous women scientists. It is not that they do not exist throughout history – it is that we need to do a better job of remembering them and telling their stories; women such as Ada Lovelace, Rosalind Franklin, and countless others.

PF: Gender bias in science is not limited to researchers themselves. The need to perform more diverse clinical studies has become a pressing issue in recent years – and it makes sense. Similarly, as we move to an age with a greater involvement of algorithms and models, there is a real fear that the AI we develop will mirror – and further reinforce – our own gender, and other, biases. What are your thoughts on this? How can this be averted?

SD: At AstraZeneca we are very conscious of the need for inclusion and diversity in our clinical trials. We have made a commitment to improve the diversity in our enrolled patients across Phase I-III trials. This can be particularly challenging with some of the diseases where recruitment is generally difficult. But the challenge exists for all clinical companies, and it is a challenge I am proud to be trying to overcome. Regarding the AI/data models it is a much easier task (low hanging fruit) as scrambling the data inputs in the models can be chosen to represent the true patients’ spectrum. We simply need to be conscious about our own prejudices and biases while creating these models. But fighting entrenched biases and promoting inclusion is something we owe to ourselves as a society – it benefits everyone!

PF: This has been an extremely productive discussion. It is always encouraging to see people succeed in fields that have traditionally been prejudiced towards other demographics. Is there anything else you would like to add to the discussion?

SD: Thank you so much for having me and for covering the gender diversity gap in such an important field!

Nick Zoukas, Former Editor, PharmaFEATURES

Dr. Sashka Dimitrievska will also be discussing the use of real world evidence in oncology trials at Proventa International’s Oncology Strategy Meeting in Boston, as well as the Clinical Operations Strategy Meeting in Boston. Join us for a day full of scientific discourse with leading stakeholders, and closed roundtable discussions on the cutting edge of the field.

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Interviews

Innovating the Canadian Biotech Sector with Joseph Mancini, adMare BioInnovations

With a wealth of globally-competitive scientific discovery, Canada is primed to lead the life sciences world. adMare is here to make that a reality!

Interviews

Leveraging Technology to Accelerate Trial Recruitment with Colleen Hoke, ObjectiveHealth

Utilizing proprietary technology, processes and trained on-site personnel, ObjectiveHealth delivers significant advances in the conduct of clinical research.

Read More Articles

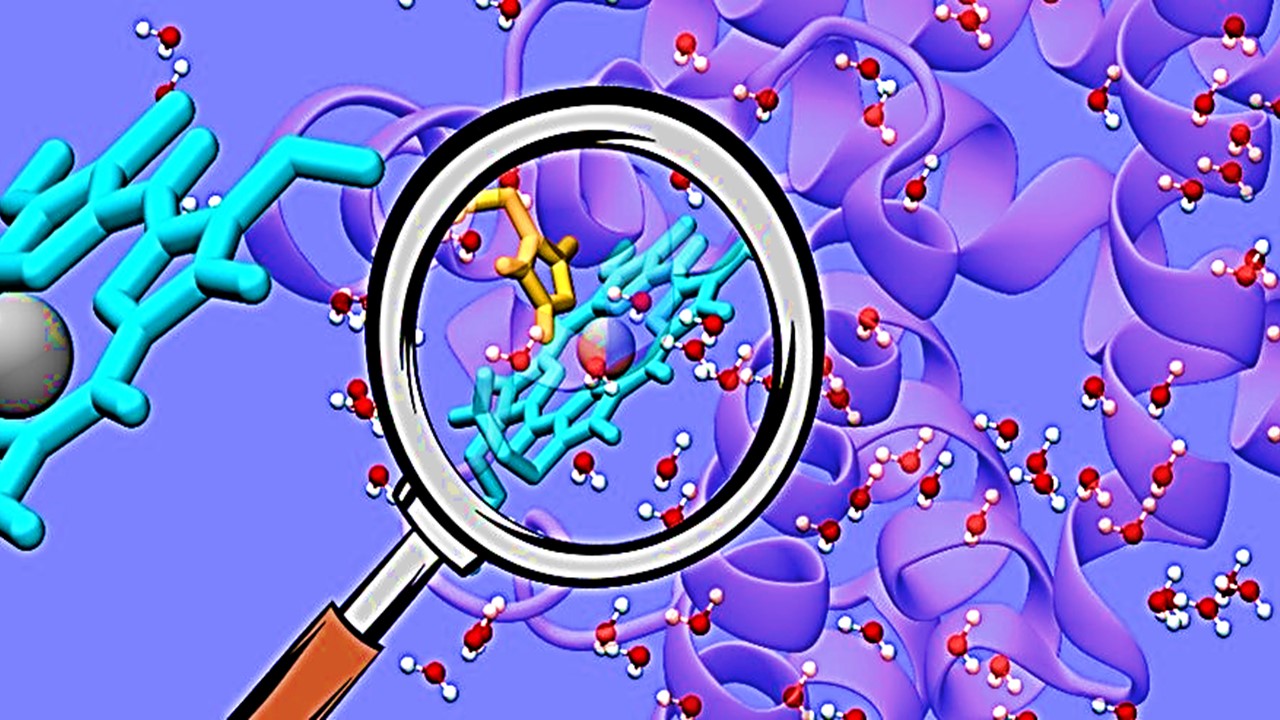

Synthetic Chemistry’s Potential in Deciphering Antimicrobial Peptides

The saga of antimicrobial peptides unfolds as a testament to scientific ingenuity and therapeutic resilience.