Dengue: An Overview

Infections with the dengue virus are widespread in hot, tropical areas. Any one of four serotypes—closely related dengue viruses—may infect a person, and these viruses can cause a variety of symptoms, from the incredibly minor to those that may necessitate hospitalization and medical attention. In extreme circumstances, deaths are possible. Although the illness itself cannot be treated, a patient’s symptoms can be controlled.

The WHO identified eleven illnesses as possible threats for 2019 earlier this year, and ongoing outbreaks in numerous countries support this finding. Seasonal patterns sometimes appear in dengue epidemics, with peak transmission occurring during and immediately following wet seasons. High mosquito populations, vulnerability to circulating serotypes, favorable air temperatures, precipitation, and humidity are some of the factors that are causing this rise. These factors all have an impact on the reproduction and feeding habits of mosquito populations as well as the incubation period of the dengue virus. Other difficulties include a lack of staff and proactive control initiatives.

Ideal Snack of Choice

A female mosquito cannot be hid from. It will locate any human by monitoring our CO2 exhalations, body heat, and odor. But some of us are definitely “mosquito magnets” who get more bites than we should. Popular explanations for why someone might be a favorite snack include things like blood type, blood sugar level, eating garlic or bananas, being a woman, and being a youngster. However, according to Leslie Vosshall, director of the Rockefeller Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior, there is not much reliable information available for the majority of them.

This is why Vosshall and Maria Elena De Obaldia, a former postdoc in her lab, set out to explore the leading theory to explain varying mosquito appeal: individual odor variations connected to skin microbiota. They recently demonstrated through a study that fatty acids emanating from the skin may create a heady perfume that mosquitoes can’t resist. They published their results in Cell.

According to her, there is an extremely robust link between having large quantities of these fatty acids on your skin and being a mosquito magnet.

The Test for Smelliness Begins

During the three-year trial, eight people had to wear nylon stockings over their forearms for six hours every day. They repeated this procedure numerous times.

The researchers tested the nylons against one another in all potential pairings over the course of the following few years in a round-robin style “tournament” using a two-choice olfactometer assay that De Obaldia built. It consisted of a plexiglass chamber divided into two tubes, each of which ended in a box that held a stocking.

They placed Aedes Aegypti mosquitoes, the main vectors of dengue, yellow fever, Zika virus, and chikungunya, in the main room.

They observed as the insects flew in one of two directions—one nylon at a time—down the tubes.

Outlier Equals Answer

Aedes aegypti found Subject 33 to be by far the most attractive target, attracting the mosquitoes 100 times more than Subject 19, the least attractive study participant, and four times more than the next most attractive subject.

As a result of the trial samples being de-identified, it was difficult for the researchers to tell which nylon had been worn by which subject. However, in any testing, insects would rush around Subject 33’s sample, giving them the impression that something was amiss.

The subjects were divided into high and low attractors, and the researchers then inquired as to what made each group unique. 50 molecular components that were augmented in the sebum, a moisturizing barrier on the skin, of the very attractive participants were found using chemical analysis techniques.

Vosshall’s team recruited an additional 56 participants for a validation study to corroborate their findings. Subject 33 continued to be the most intriguing subject throughout time.

This led them to the conclusion that mosquito magnets produced carboxylic acids at substantially higher amounts than the less attractive participants. Our distinct human body odor is created by bacteria on our skin using ingredients found in the sebum.

Mosquito Repellent of the Future, Still Far Ahead

Mosquitoes have two distinct sets of olfactory receptors, known as Orco and IR receptors, which they use to detect primarily two groups of human scents. The researchers developed mutants lacking one or both of the receptors to explore if they might make mosquitoes that were unable to detect humans. While IR mutants lost their attraction to us to varying degrees but still had the ability to locate us, Orco mutants continued to be drawn to humans and were able to distinguish between mosquito magnets and low attractors.

The scientists had not anticipated these findings. The ideal mosquito would have no attraction to humans, or would have a weaker attraction to everyone and be unable to distinguish between Subject 19 and Subject 33. If this is confirmed, it might encourage the creation of stronger insect repellents. Unfortunately, that was not the observed outcome.

The redundancy of the extraordinarily intricate olfactory system in Aedes aegypti was shown by one of Vosshall’s recent investigations, which was also published in Cell. These findings support that study. For the female mosquito to survive and procreate, it serves as a safeguard. She is powerless without blood. She is aware of these variations in the skin chemistry of the individuals she targets and has a backup plan, another backup plan, and a backup plan for the backup plan.

Let Microbiology Save the Day!

It is challenging to imagine a world in which humans are not the main course on the menu due to the mosquito scent tracker’s ostensible impeccability. However, altering the microbiomes on our skin is one option. It’s likely that applying sebum and skin bacteria from the skin of a low-appeal person, like Subject 19, to the skin of a high-appeal person, like Subject 33, could have the effect of hiding mosquitoes.

Vosshall makes it clear that such an experiment has not yet been conducted and that it would be challenging to carry out. However, one could see a microbiome or dietary intervention where bacteria are applied to the integument and they would interact dynamically with the sebum if it were to truly function. We can change a Subject 33 into a Subject 19 in this way. But everything is just conjecture.

The goal of Vosshall and her colleagues’ project is to promote more study of other mosquito species, especially those belonging to the genus Anopheles, which is known for transmitting malaria. Untangling the universality of this strategy would be a game-changer.

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Infectious Diseases & Vaccinology

Rezzayo™’s Latest EU Approval for Invasive Candidiasis Breaks Ground in Antifungal Therapy

Rezafungin marks the initial addition to the treatment arsenal for patients grappling with invasive candidiasis in more than 15 years.

Infectious Diseases & Vaccinology

Unmasking the Shadow: CDC Battles the Latest Fungal Meningitis Outbreak in Matamoros, Mexico

CDC tackles fatal fungal meningitis outbreak linked to surgeries in Matamoros, Mexico.

Read More Articles

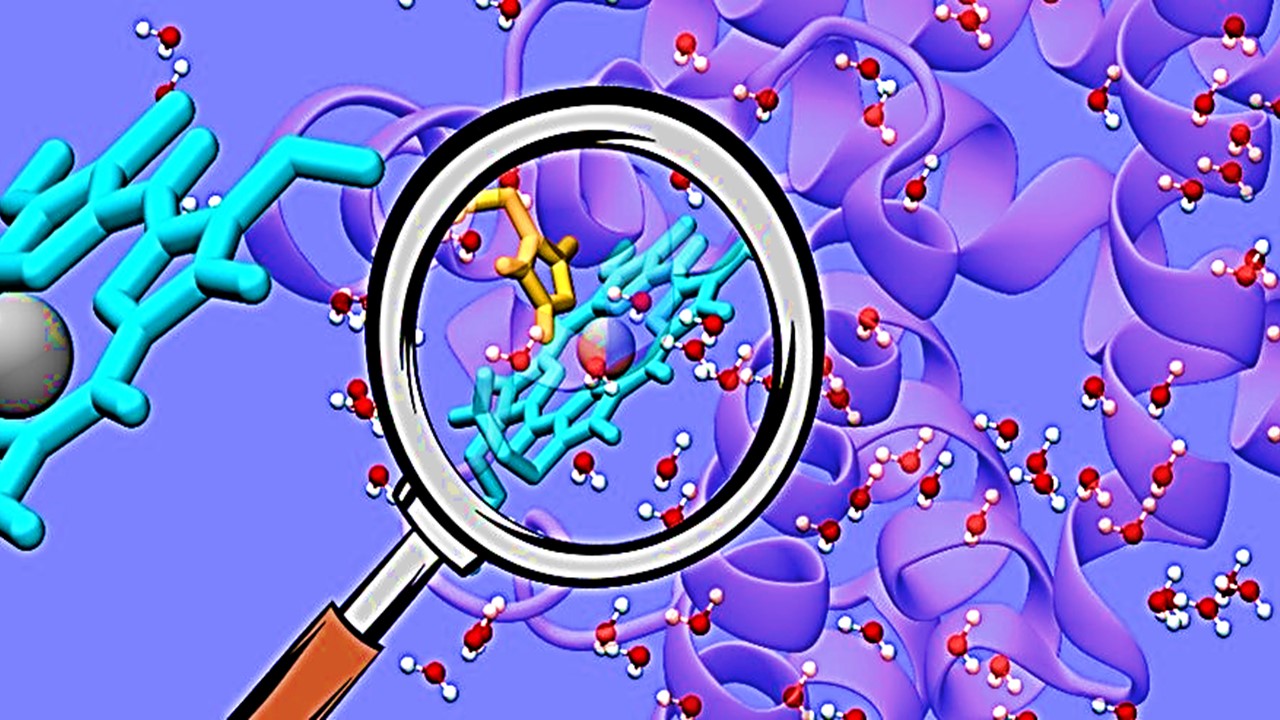

Synthetic Chemistry’s Potential in Deciphering Antimicrobial Peptides

The saga of antimicrobial peptides unfolds as a testament to scientific ingenuity and therapeutic resilience.