The pandemic has understandably increased the health literacy of the public. Faced with misinformation and fake news regarding the COVID-19 virus and the vaccines or treatments available for it, governments and industry stakeholders have had to ensure that information on drug safety is readily accessible to interested parties. This, as well as the drive towards precision medicine, are raising the relevance of pharmacovigilance across the industry: documenting and communicating the safety of the drugs we develop is becoming a more complex and crucial endeavor. To fulfill the increased needs of the field, we not only need to harness innovative technologies – but also diversify the data sources we rely on.

Clinical Safety

Much of the clinical development effort put into advancing a novel therapeutic is directed at ensuring its safety profile is acceptable – acceptability can vary wildly depending on the benefit the drug offers. Thus, the adverse events related to any pharmaceutical can generate substantial patient and healthcare costs and burdens – which is why it is often so important to record them early during development. However, clinical trials face their own limitations: the sample size will always be limited – and the diversity of the study’s participants may restrict the effects which can be observed. This is one of the reasons why addressing the lack of diversity in clinical trials remains a pressing concern – particularly as decentralization offers unique opportunities to do so.

In addition, drug developers do not all have the same resources for large scale clinical trials – studying the totality of adverse events presented by a pharmaceutical can often lead to excessive costs when a drug has already been deemed safe enough. These, and many other reasons, are why the mission for drug safety does not end when clinical development ends: more emphasis is increasingly placed upon post-marketing surveillance, where adverse events are recorded once the drug has been put out in the market. The post-marketing surveillance stream relies on a diversity of sources: these include traditional data flows such as medical literature, registries, electronic health records and reports generated by healthcare practitioners – a report published by the European Union made full recommendation on the use of such databases.

Beyond Traditional Post-Marketing Surveillance

However, there is still room to diversify further. We increasingly see more efforts into exploring alternative data sources for post-marketing surveillance – these often include data generated through smart technologies and social media. Such avenues present unique opportunities to record adverse events that would otherwise be missed by traditional data routes – often due to underreporting or simply a lack of awareness that they may present a side effect or interaction. The long-standing challenge with harnessing “big data” sources such as online forums, social networking sites and other – especially unstructured – data sources has been their sheer volume and the capacity needed to distill the information they present. This is being enabled by emerging technologies promising to transform the field – particularly Natural Language Processing (NLP) models, including those powered by Artificial Intelligence. NLP can draw information across very fragmented and heterogeneous sources and condense it into workable data which can then be used for safety analyses.

For example, a study showed that data mining using NLP methods was able to analyze the timelines of 6927 users (including over 5,329,720 posts) on Instagram to identify drug interactions for depression medications – indicating the potential of quantitative network analyses in public health monitoring and pharmacovigilance. Even traditional sources can benefit from these novel technologies and methods – studies show the potential of using data mining on medical literature and databases, in addition to social media, to identify drug-drug interactions (DDIs). It could be argued that the use of alternative data sources and emerging technologies for DDIs is even more critical than for adverse events – clinical trials rarely have the resources to investigate all meaningful interactions, and a larger focus is placed on post-marketing surveillance to assess DDIs. Other sources ripe for data mining include search histories and logs regarding marketed drugs – which can shed a light into patient experiences.

The challenges in using these data sources are obvious: the data volume is enormous, heterogeneous and often unverifiable. In addition, we are trading the controlled diversity of clinical trials for a population whose diversity we have no control over – but a population that is also biased towards younger, more internet-savvy individuals. As the field of NLP and data mining alternative sources of information is explored, it is crucial that we set better benchmarks for what constitutes a signal. Regulators also have a large role to play in validating the reliability of novel data sources. As our tools and models improve, the volume of data we will be able to process will increase exponentially – but collaboration is needed to standardize this emerging field.

Join our Pharmacovigilance Strategy Meeting in London in 2022 to hear more on the role alternative data sources have to play in drug safety – discuss the subject with world-renowned experts and tackle questions faced by everyone in the industry as they seek to adopt the latest technologies and methods

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

AI, Data & Technology

The Power of Unsupervised Learning in Healthcare

In healthcare’s dynamic landscape, the pursuit of deeper insights and precision interventions is paramount, where unsupervised learning emerges as a potent tool for revealing hidden data structures.

Bioinformatics & Multiomics

Harnessing Computational Ingenuity for Tomorrow’s Therapeutics

Leverage computational power to navigate modern drug design.

Read More Articles

Synthetic Chemistry’s Potential in Deciphering Antimicrobial Peptides

The saga of antimicrobial peptides unfolds as a testament to scientific ingenuity and therapeutic resilience.

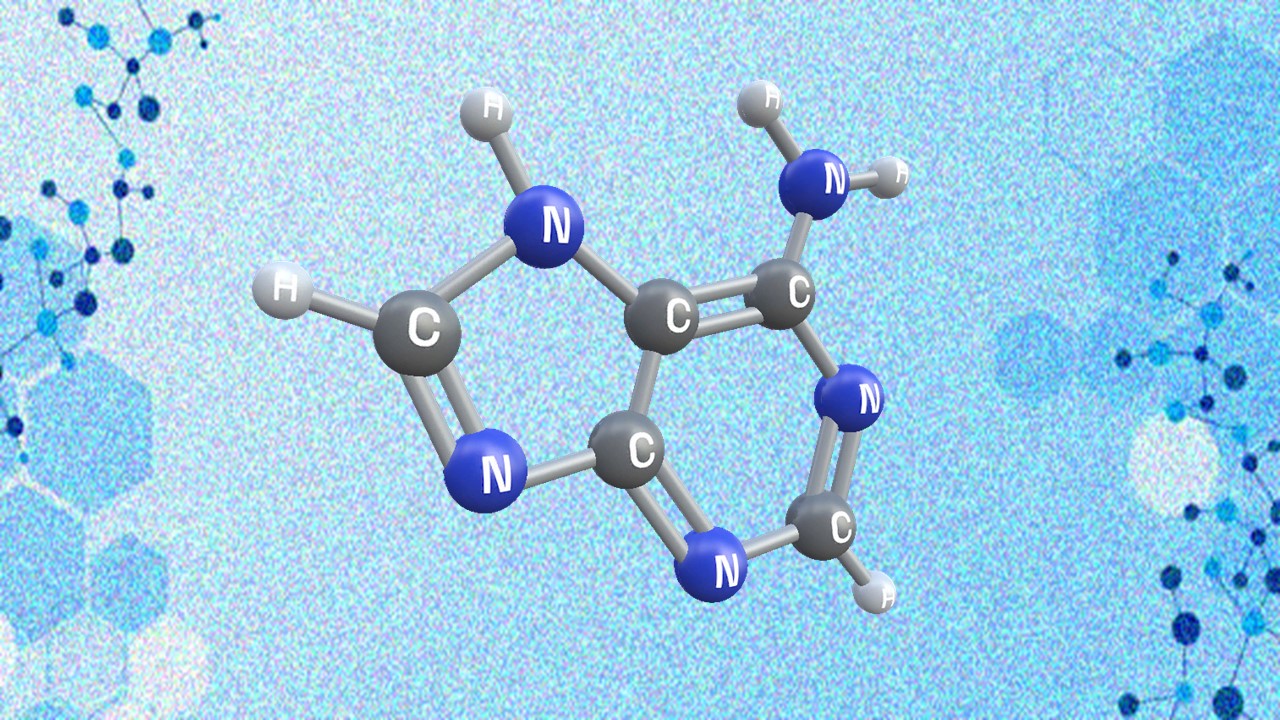

Appreciating the Therapeutic Versatility of the Adenine Scaffold: From Biological Signaling to Disease Treatment

Researchers are utilizing adenine analogs to create potent inhibitors and agonists, targeting vital cellular pathways from cancer to infectious diseases.