Cell and gene therapies have remained at the forefront of biomedical research for the last decade. While the mechanisms of these therapies differ, both approaches have shown potential across a range of conditions to alleviate symptoms or potentially cure the underlying disease. The latest research is focusing on the future for viral- and non-viral based vectors for cell and gene therapy.

Gene therapy is a broad term which covers methods that improve the genetic profile of an organism by “means of the correction of altered (mutated) genes or site-specific modifications that have therapeutic treatment as target”. Cancer gene therapy is an example of this therapeutic technique which continues to show potential in cancer research for treatment.

A number of innovations and findings came from CGT research in 2020, as highlighted in a recent Nature article. One interesting finding was that a new genetic signature was identified for acute myeloid leukemia. This genetic signature is important in detecting AML-specific stem cells that are responsible for tumor relapse and therapy resistance.

A recent study used machine learning algorithms to develop a method of identifying genes associated with stem cells. These genes were considered as specific biomarkers for leukemia stem cells. This could have a fundamental impact on future gene therapy design, in terms of optimising cancer stem cell identification and validation through biomarkers.

Stem cell therapy is also an example of a cellular therapeutic technique which has shown potential as a regenerative strategy for a multitude of diseases. Cell therapy is characterised as the “prevention or treatment of human disease by the administration of cells that have been selected, multiplied, and pharmacologically treated or altered outside the body (ex vivo)”. The cells may be derived from the patient known as autologous cells or from a donor (allogeneic cells).

In ophthalmology, stem cell therapy has seen a significant improvement in the vision of patients suffering from a condition known as macular degeneration. This was reported after patients of a particular study received a transplant “patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that were induced to differentiate into pigment epithelial cells of the retina”.

Viral vector-based therapy

Traditional viral vector-based gene therapy is achieved by in vivo delivery of the “therapeutic gene into the patient by vectors based on retroviruses, adenoviruses (ADs) or adeno-associated viruses (AAV)”.

ADs continue to be used as a vector for CGT due to a number of advantages. Firstly, they show high transduction efficiency for a broad range of cell types. Transduction refers to the entry of viral vectors into the target cells. In the case of AD this is a rapid, simple process which allows “sufficient expression of the encoded sensor to permit detection and analyses”. Secondly, they have the ability to infect a broad range of cell types and tissue, known as viral tropism.

Third-generation AD vectors, known as high-capacity AD viral vectors (HCAds), are the latest versions of developed viral vectors for gene therapy. HCAds are characterised as high capacity due to their ability to accommodate ~36 kb of space for cargo genes. In comparison with previous generations, HCAds offer a number of improvements.

One of the main improvements is that HCAds demonstrate a reduced immunogenicity. Immunogenicity refers to the ability of therapeutic products to trigger an immune response. While this may be desirable in the context of vaccines, it is an unwanted effect with viral vectors which are then cleared or neutralised by the immune system. In addition, immunogenicity of gene therapy products “can cause diverse immune related toxicities”.

The future for AD viral vectors is further refinement with elimination of the current limitations. While the immunogenicity has been reduced in third generations, AD viral vectors pose a concern over the safety in the long term. In 2019, a ten-year follow up study in dogs receiving gene therapy vectors, found that “the vector genomes were found to be stably integrated into the host genome”. This presents some obvious concerns with regards to the risk of oncogenic mutations. Lentiviruses, another type of viral vector, are emerging as a platform of choice for genetic vaccines. Recent advances in the development of non-integrating lentiviral vectors have greatly reduced insertional mutagenesis.

Non-viral approach

The main advantage of moving towards non-viral vectors in CGT is the biosafety. In comparison to viral vectors which pose a risk for immunogenicity and cytotoxicity, non-viral vectors offer a significant safety advantage.

In terms of manufacturing, they are also more cost-effective and easier to produce than viral vectors. The major approaches to non-viral gene delivery involve naked DNA, plasmids, conjugate complexes and cationic polymers.

Plasmids

A plasmid is a small, circular, double-stranded DNA molecule that is distinct from a cell’s chromosomal DNA. Researchers can insert genes into a plasmid vector creating a recombinant plasmid. The plasmid is transferred into a bacterium in a process called transformation, which then undergoes rapid division and can be used as factories to copy DNA fragments in large quantities.

One of the main problems with plasmid vectors is translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus. The cytosol is typically the desired location for transported cargo to induce a therapeutic effect, the nucleus is often avoided due to the risk of genetic alterations.

Cationic polymers

In the last decade, molecular biology has seen significant development in the engineering of non-viral vectors. Plasmid vectors, while originally popular, are decreasing in prevalence in CGT. Cationic polymers are now among the most utilised non-viral vectors for gene transfer.

This class of non-viral, lipid-based vectors includes polyethyleneimines (PEI). PEIs have demonstrated good gene delivery performance with regards to a high cation charge density. A high cation charge refers to a density of positively charged ions, which shows great attraction for DNA and RNA, which are both negatively charged.

Polysaccharides

In terms of future development, bioengineering appears to be moving towards polysaccharides as gene delivery systems. Polysaccharides are long chains of subunits called monosaccharides – glucose is a prime example of an important polysaccharide.

A number of natural polysaccharides such as chitosan and hyaluronic acids have been widely used as polymeric backbones for the formation of nanoparticles, which can be provided as valuable gene delivery carriers. They show substantial promise for cell therapy, “effectively transporting the drug molecules across the membrane“. In addition, their biodegradability ensures the release of the encapsulated drug molecules, which minimises the side effects caused by a burst release of the cargo therapeutics.

Despite the innovations improving viral-vectors for molecular medicine, non-viral vectors appear to offer significant advantages. In addition to minimising safety concerns, the manufacturing process of non-viral vectors is overall more simple and cost-effective. However, further research is required to refine non-viral vectors to meet the therapeutic efficacy of viral vectors should they become an alternative.

Charlotte Di Salvo, Lead Medical Writer

PharmaFeatures

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Cell & Gene Therapy

Eyeing the Future: Stem Cells and the Promise of Corneal Restoration

By reducing dependency on donor tissues and minimizing immunosuppressive demands, iCEPS has the potential to redefine LSCD treatment.

Cell & Gene Therapy

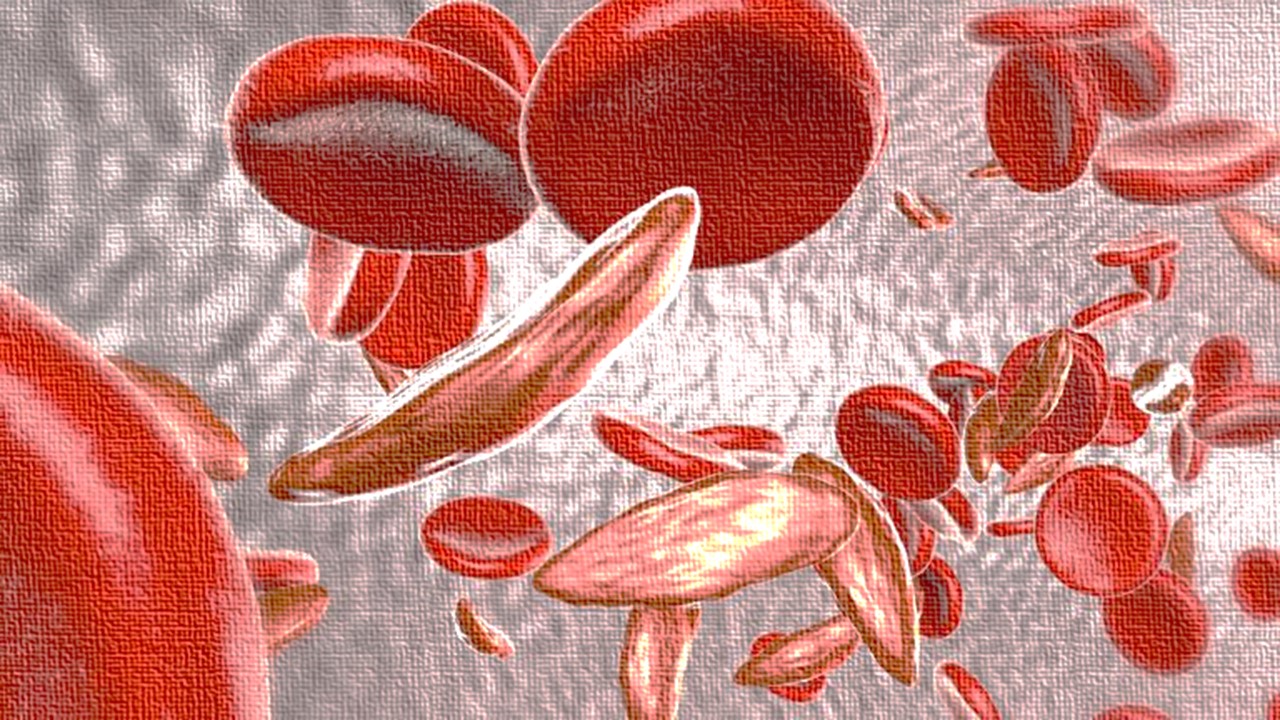

A Cure in the Code: How Gene Editing is Transforming the Fight Against Sickle Cell Disease

BIVV003’s success highlights gene editing’s potential to treat genetic disorders at their root, offering hope for other conditions.