The Proteome’s Hidden Architecture: Beyond Static Structures

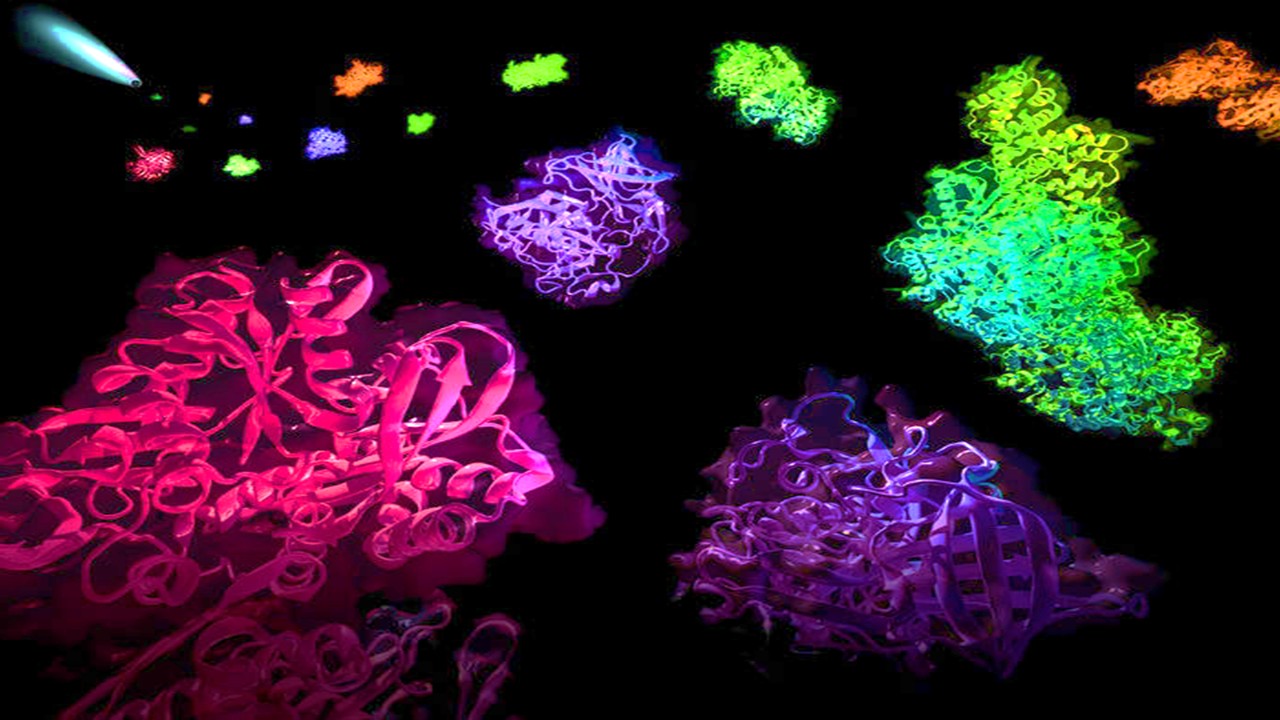

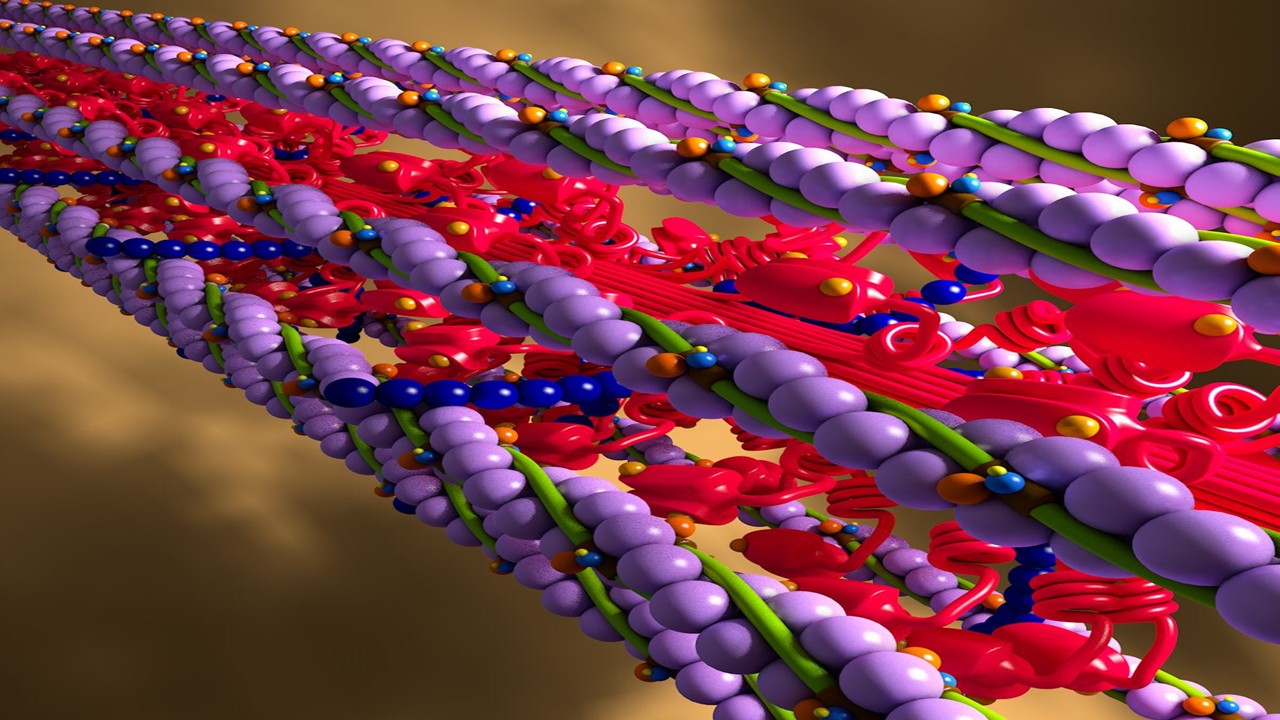

The human genome’s paradox—its modest 19,000 genes encoding a staggering biological complexity—hints at a deeper narrative woven into the proteome. Proteins, far from static entities, exhibit dynamic structural plasticity that underpins their functional versatility. This dynamism spans alternative sequences, conformations, interactions, and localizations, collectively forming a “proteoform” landscape. Proteoforms, generated through mechanisms like alternative splicing and post-translational modifications (PTMs), enable a single gene to yield multiple protein variants. For instance, phosphorylation or acetylation can alter a protein’s activity, localization, or interactions, effectively rewiring cellular pathways without genetic changes.

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) further challenge traditional structural paradigms. Lacking fixed three-dimensional folds, IDPs adopt transient conformations that facilitate interactions with diverse partners. These molecular chameleons are enriched in regulatory hubs, such as transcription factors and signaling proteins, where structural fluidity allows rapid response to cellular cues. The concept of “conformational proteoforms” has emerged to describe IDPs’ ability to toggle between functional states, underscoring their role in processes from synaptic plasticity to Wnt signaling.

Cellular complexity also arises from spatiotemporal regulation. Proteins shuttle between organelles, adopting context-dependent roles. The tumor suppressor APC, for example, navigates nuclear and membrane compartments, leveraging its disordered regions to assemble transient complexes. Such spatial dynamics, coupled with proteome-wide variation in protein half-lives—from minutes to decades—create a kinetic landscape where transient interactions and localized concentrations drive emergent biological order.

Dynamic Duos: Alternative Structures and Functional Plasticity

Protein interactions defy the rigid “lock-and-key” model, embracing conformational adaptability. Bacterial Lac repressor proteins, for instance, transition from disordered “fuzzy” complexes when scanning DNA to structured conformations upon target binding. Similarly, transcription factor LEF1 folds into a defined structure only when bound to DNA, illustrating how disorder enables precise molecular recognition. These dynamic transitions are not mere curiosities; pathological misfolding of α-synuclein into amyloid fibrils underlies Parkinson’s disease, highlighting the dual-edge of structural plasticity.

IDPs serve as linchpins in interaction networks. The adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein, with its extensive disordered regions, orchestrates Wnt signaling by assembling multi-protein complexes. Mutations truncating these regions disrupt signaling, linking disorder loss to cancer. Conversely, Axin1’s folded domains, when mutated, trigger aberrant interactions, demonstrating how subtle structural perturbations propagate dysfunction. This continuum from order to disorder—a spectrum rather than a binary—reveals how evolution exploits flexibility to balance specificity and promiscuity.

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) further diversify proteoforms. A single protein modified at different sites can switch roles, as seen in histones, where acetylation modulates chromatin accessibility. This regulatory layer, combined with alternative splicing, exponentially expands functional diversity. Yet, quantifying these dynamic states remains a challenge, necessitating methods that capture transient modifications and interactions in vivo.

Structural Biology Reimagined: From Crystals to Cryo-EM

X-ray crystallography, once the gold standard for static structures, now illuminates disorder. Regions lacking electron density in crystallized proteins—once dismissed as artifacts—are now recognized as disordered segments. Advances like time-resolved crystallography capture ultrafast dynamics, such as light-induced isomerization in photoactive proteins, offering glimpses into conformational transitions. Meanwhile, NMR spectroscopy and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) complement crystallography by resolving flexible regions in solution. Cryo-EM’s resolution inversely correlates with flexibility, enabling visualization of disordered domains in large complexes like ribosomes.

Cryo-EM’s renaissance, driven by detector advancements, has democratized structural insights for complexes exceeding 150 kDa. NMR, though limited to smaller proteins, uniquely probes dynamics across timescales, from picosecond side-chain motions to slow folding events. Together, these techniques reveal how IDPs like c-Myc adopt structured conformations upon binding partners, suggesting druggable interfaces. However, technical hurdles persist: sample preparation remains finicky, and integrating dynamic data into cohesive models demands computational innovation.

Biochemical methods like limited proteolysis (LiP) bridge structural and systems biology. By digesting exposed protein regions, LiP maps conformational changes proteome-wide. Recent studies combining LiP with mass spectrometry unveiled structural shifts in hundreds of yeast proteins under metabolic stress, proving that traditional assays, when scaled, can yield global insights. These approaches, though low-resolution, contextualize structural dynamics within cellular milieus.

Biochemical Sleuths: Probing Protein Conformations

Thermal and chemical stability assays offer windows into protein folding. The cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) monitors ligand-induced stabilization, revealing drug-target engagement in live cells. Thermal proteome profiling (TPP) scales this principle, profiling stability shifts across thousands of proteins, uncovering off-target effects and membrane protein behaviors. Surprisingly, membrane proteins exhibit greater stability in native bilayers than in detergent micelles, explaining their crystallization challenges.

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX) tracks structural fluctuations by measuring backbone amide exchange rates. Rigid regions retain deuterium longer, while disordered segments exchange rapidly. Reverse HDX has even mapped peptide-protein interactions proteome-wide, hinting at future applications in vivo. Innovations like acid-compatible proteases could minimize back-exchange artifacts, enabling HDX in living systems.

Pulse proteolysis and FASTpp exploit proteolytic susceptibility to assess folding. FASTpp’s thermal denaturation detects mutation-induced destabilization or ligand binding, offering a rapid screen for structural perturbations. These methods, though simplistic, provide high-throughput data complementary to high-resolution techniques, illustrating how classical biochemistry fuels modern proteomics.

Mapping the Invisible: Labeling and Solubility Techniques

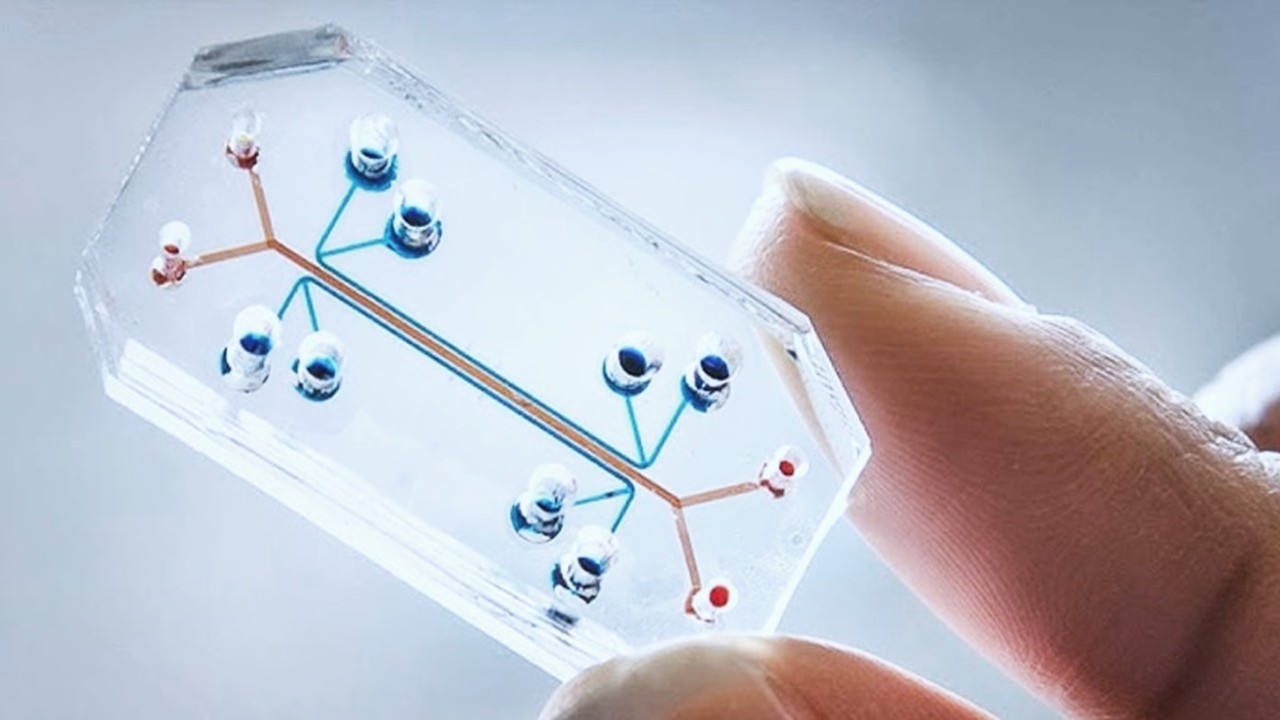

Proximity-labeling strategies like APEX2 and BioID tag interacting proteins in vivo, circumventing affinity purification’s limitations. APEX2-generated biotin radicals label nearby proteins, capturing transient interactors in organelles or membrane microdomains. SPPLAT, using horseradish peroxidase, achieves similar goals with reduced cellular stress. However, enzyme compatibility and labeling efficiency vary, necessitating method-tailoring to biological contexts.

Biotin ligase mutants (BioID) enable promiscuous biotinylation, identifying interactors over time. BioID2, optimized for human cells, enhances labeling efficiency, though thermostability issues persist. Peptide-level enrichment, bypassing protein-level biases, boosts detection sensitivity, promising deeper interactome maps. These techniques, paired with cryo-ET or super-resolution microscopy, could resolve subcellular interaction niches.

Solubility-based methods like hyperLOPIT map protein localization across organelles. By coupling density gradient fractionation with TMT labeling, hyperLOPIT assigns thousands of proteins to subcellular compartments, revealing multi-localized players like APC and BRCA1. Such maps contextualize protein function, linking PTMs or splice variants to organelle-specific roles, though challenges remain in capturing transient localization shifts.

Transient Interactions: The Subtle Language of Cellular Networks

Weak, transient interactions underpin cellular networks, enabling rapid signal transduction. The ACTR-NCBD complex exemplifies mutually induced folding, where two disordered proteins coalesce into a structured heterodimer. Such interactions, though low-affinity, drive transcriptional regulation, suggesting that cellular context—crowding, chaperones—modulates binding efficacy.

Crosslinking mass spectrometry (XL-MS) captures these fleeting interactions in vivo. MS-cleavable crosslinkers like DSSO stabilize complexes without disrupting MS analysis, enabling structural modeling of dynamic assemblies. Future in vivo XL-MS could map interaction topologies under physiological conditions, though current limitations in crosslinker permeability and peptide identification persist.

Single-molecule interaction sequencing (SMI-seq) quantifies binding affinities multiplexedly, addressing the validation bottleneck. By crosslinking proteins to DNA barcodes, SMI-seq profiles hundreds of interactions in parallel, revealing affinity landscapes for soluble and membrane proteins. Such platforms, integrated with CRISPR libraries, could systematically map interaction networks, bridging biophysics and systems biology.

Organelles and Beyond: Spatial Dynamics in Protein Function

Membrane-less organelles, like stress granules, emerge via liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), driven by IDPs with low-complexity domains. These compartments concentrate biomolecules, tuning reaction rates and sequestering components during stress. The prion-like domain of Xvelo, for instance, assembles Balbiani bodies in oocytes, illustrating how disorder generates cellular asymmetry.

Organelle proteomics, via hyperLOPIT or PCP, maps multi-localized proteins, linking splice variants or PTMs to compartment-specific functions. Wnt pathway components, enriched in IDRs, exemplify proteins shuttling between nuclei and membranes to regulate development. Such spatial dynamics, visualized by cryo-ET or mass spectrometry imaging, underscore the proteome’s topological adaptability.

Morphogen gradients, like Wnt, pattern tissues through non-diffusive mechanisms, requiring dynamic protein assemblies. APC’s disordered regions facilitate gradient sensing, enabling precise spatial signaling. Dysregulation of these processes, as in autism-linked APC mutations, highlights the functional imperative of proteome dynamics in tissue architecture.

Computational Frontiers: Modeling Proteome Complexity

Computational tools integrate multi-omics data, predicting structures, interactions, and dynamics. AlphaFold and Rosetta have advanced folded domain prediction, while force fields like CHARMM36m now model IDP ensembles. Machine learning algorithms analyze hyperLOPIT or TPP datasets, identifying patterns linking sequence features to localization or stability.

Principal component analysis (PCA) reduces proteomic data dimensionality, visualizing localization trends (Fig. 2). Yet, challenges persist: predicting in vivo interactions from sequence alone remains elusive, and integrating multi-omics layers demands novel algorithms. Community efforts like CASP benchmark progress, but a holistic proteome model—a “4D” map integrating time and space—remains aspirational.

Future directions include de novo organelle engineering guided by proteome dynamics. Early examples, like optimizing photosynthetic pathways, hint at synthetic biology applications. As proteomics transitions from descriptive to predictive, bridging experimental and computational realms will unlock therapeutic breakthroughs, transforming our grasp of life’s dynamic blueprint.

The Ordered Chaos of Life

The proteome’s complexity emerges from its intrinsic disorder—a paradox where fluidity begets precision. Advances in structural biology, biochemistry, and computation are unraveling this dynamism, revealing how conformational ensembles, transient interactions, and spatial gradients encode biological function. As methods evolve to capture these layers in vivo, the proteome’s hidden logic—a symphony of disorder and order—promises to reshape medicine, biotechnology, and our understanding of life itself.

Study DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201600399

Engr. Dex Marco Tiu Guibelondo, B.Sc. Pharm, R.Ph., B.Sc. CpE

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Molecular Biology & Biotechnology

Myosin’s Molecular Toggle: How Dimerization of the Globular Tail Domain Controls the Motor Function of Myo5a

Myo5a exists in either an inhibited, triangulated rest or an extended, motile activation, each conformation dictated by the interplay between the GTD and its surroundings.

Drug Discovery Biology

Unlocking GPCR Mysteries: How Surface Plasmon Resonance Fragment Screening Revolutionizes Drug Discovery for Membrane Proteins

Surface plasmon resonance has emerged as a cornerstone of fragment-based drug discovery, particularly for GPCRs.

Read More Articles

Designing Better Sugar Stoppers: Engineering Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors via Fragment-Based Dynamic Chemistry

One of the most pressing challenges in anti-diabetic therapy is reducing the unpleasant and often debilitating gastrointestinal side effects that accompany α-amylase inhibition.