Over the past few years, increasing evidence has supported the role of biomarkers in immunotherapy. Combination therapy – the use of a combination of products or modalities to treat cancer – is one way to use biomarkers to reveal the tumour microenvironment and identify targets for specific immunotherapy treatment. Recent advances in clinical research are beginning to show the potential of combination therapy as a more effective and tolerable treatment option.

Therapeutic targets in cancer genetics

Abnormal epigenetic modifications are a hallmark of malignant tumours. The role they play in cancer, however, continues to be disputed. While the direction of cancer research continues to decipher the role of these modifications in cancer cells, an increasing number of studies are specifically focusing on understanding the impact of epigenetic modifications within the tumour microenvironment (TME).

The evolution of cancer is greatly dependent on the complex tumour microenvironment from which it grows and metastasises. Immunosuppression plays a key role in the TME, and arises from epigenetic modifications in tumour-associated immune cells. One example is the epigenetic modification of Tregs in cancer (T-cell population which is essential for immune tolerance). As a result of these genetic alterations to Tregs, their functional role becomes maladaptive which results in maintaining an immunosuppressive TME.

Understanding the role of the immune system, as well as the complex molecular subtypes in different tumours, highlights a significant knowledge gap that could be used to improve immunotherapy combinations. The efficacy of immuno-monotherapy is inconsistent across patient cohorts, with increasing evidence for predictive biomarkers that foresee treatment response. The clinical evidence and necessity for effective therapeutic treatment supports the rationale for combining epigenetics with immunotherapy to target the dysfunctional immune response within the tumour microenvironment.

Identifying immune biomarkers in cancer

The initial stage in targeting genetically-modified immune cells is the identification of biomarkers. In order to target biomarkers, there must be a sufficient quantity of these biomarkers present in tumour cells, and all need to be expressed in the same way, known as homogeneous expression.

The traditional method of classifying biomarkers in cancer is immunohistochemistry (IHC). IHC is a staining technique which uses selective antibodies to quantify the distribution of molecular markers in cancerous tissue. The classical methods of IHC use chromogenic or fluorophore detection, which identifies and localises proteins in tissue sections. More advanced methods such as fluorescence in situ hybridisation and cDNA microarray are becoming more popular in clinical practice. In comparison to ICH however, these techniques have been argued to lack the practical properties of IHC.

In addition to forming a basis for therapeutic treatment, ‘immuno-biomarkers’ have been used as a prognostic tool. The “immunoscore” quantifies the density of lymphocyte populations at the tumour centre and at the invasive margin. The scoring system ranges from low immune cell densities (0) to high densities with an immunoscore of 4: the higher the score, the greater the prognosis for long-term patient survival.

Challenges and opportunities ahead

Despite immunotherapy representing one of the most effective anti-cancer treatments, there are obvious clinical flaws. The time required to trigger and establish immune-effector mechanisms results in a delayed clinical response . This can lead to tumour “flare ups” which compromises the efficacy of treatment. Furthermore, the efficacy of immunotherapy is not consistent across patient groups. Patients with weaker immune systems will struggle to generate a sufficient anti-tumour response with treatment.

In order to increase the clinical benefit of immunotherapy, one strategy has been to combine the method with inhibitor checkpoint mechanisms. Immune checkpoints are components within the immune system which prevent healthy cells from being destroyed by a strong immune response.

The inhibition of immune checkpoint molecules such as programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) have shown great efficacy across many cancer types. The blocking of these immune checkpoints prevents an “off” signal from being transmitted which would otherwise prevent T-cells from destroying cancer cells. A recent study in sarcoma patients demonstrated a positive response to immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy.

Tumour DNA methylation events are modifications to the DNA structure via enzymes, and are increasingly being used as biomarkers in oncology. The events which are considered “pathophysiological highly relevant in tumorigenesis” have been suggested to improve differential diagnosis of carcinomas. In the above study, a broad profiling of DNA methylation was performed in a series of adult patients with sarcoma in addition to treatment with anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitory (ICI) therapy.

The aim of the study was to determine whether “tumour DNA methylation profiling could serve as a predictive biomarker of response to specific therapies including … targeted and immunotherapy”. By adjusting the data, the study highlighted methylation differences between patients who responded and those who did not to anti-PD1 treatment. In addition to an objective response rate of 22.9% to treatment, the identification of methylation differences relative to treatment response is promising. The results suggest that these profiles could act as predictive biomarkers for response to anti-PD ICI.

Additional clinical evidence from a recent phase 2 study supports the rationale for biomarker combination immunotherapy. The standard first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is axitinib, a cancer growth blocker, but patient survival on the drug is inconsistent. In the study, adult patients were treated with a combination of axitinib and pembrolizumab, an anti-PD1 antibody which selectively inhibits the PD1 immune checkpoint. The overall response rate was 25.6%, with treatment tolerated well by patients with advanced RCC.

In addition, immunophenotype assays (which classify immune cells present) showed elevated immunity against tumours after combination treatment, especially in patients with “long-term survival benefit”. The results of this trial not only support combination treatment for tolerability and potential efficacy, but that immunophenotypic profiles could be utilised as prognostic biomarkers.

By understanding the overlap between the molecular changes of TMEs and biomarkers, researchers may be able to better identify cohorts who will respond well to combination immunotherapy in the future.

Charlotte Di Salvo, Lead Medical Writer

PharmaFeatures

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Immunology & Oncology

The Silent Guardian: How GAS1 Shapes the Landscape of Metastatic Melanoma

GAS1’s discovery represents a beacon of hope in the fight against metastatic disease.

Immunology & Oncology

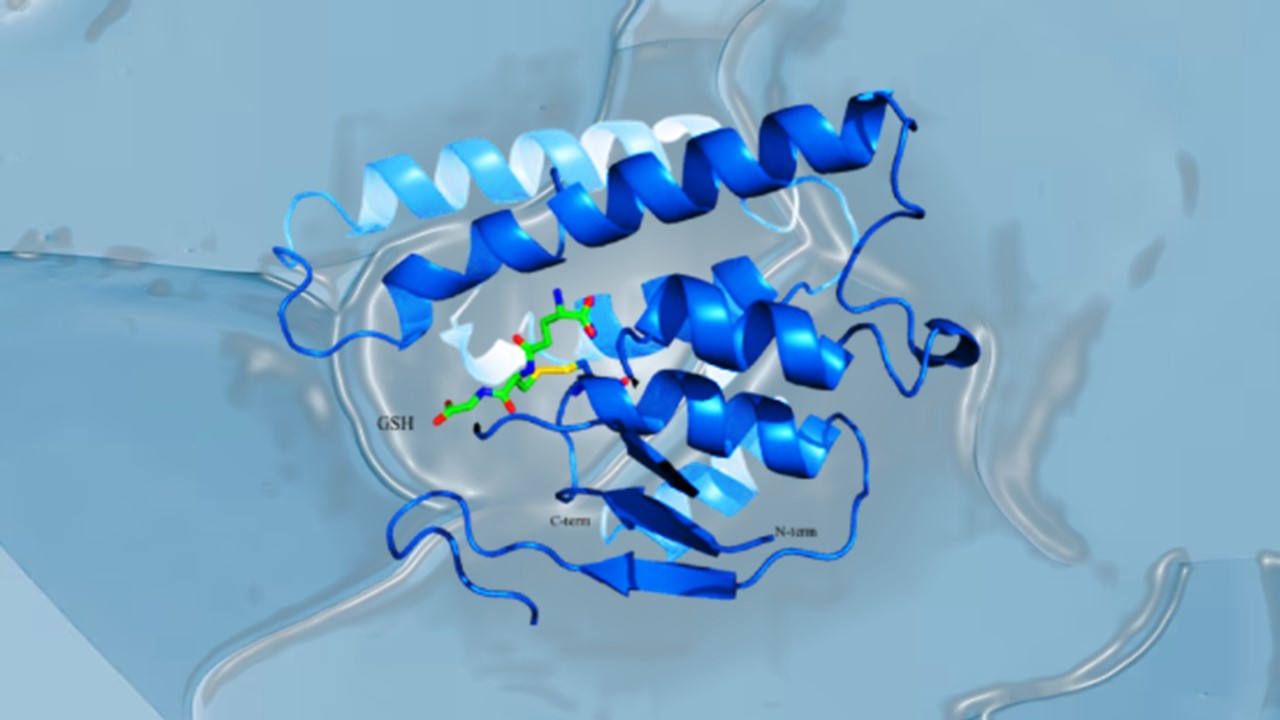

Resistance Mechanisms Unveiled: The Role of Glutathione S-Transferase in Cancer Therapy Failures

Understanding this dual role of GSTs as both protectors and accomplices to malignancies is central to tackling drug resistance.

Read More Articles

Myosin’s Molecular Toggle: How Dimerization of the Globular Tail Domain Controls the Motor Function of Myo5a

Myo5a exists in either an inhibited, triangulated rest or an extended, motile activation, each conformation dictated by the interplay between the GTD and its surroundings.

Designing Better Sugar Stoppers: Engineering Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors via Fragment-Based Dynamic Chemistry

One of the most pressing challenges in anti-diabetic therapy is reducing the unpleasant and often debilitating gastrointestinal side effects that accompany α-amylase inhibition.