Every hour, two more people are diagnosed with Parkinson’s in the UK and the global patient population continues to rise. To date, there are no disease-modifying therapies available on the market for Parkinson’s (PD) patients. Pharmaceutical company Bayer is simultaneously launching stem cell therapy and gene therapy trials for Parkinson’s patients. The aim of this is to reverse the decline in motor control caused by the disease.

Introduction

Parkinson’s is a progressive neurodegenerative disease in which depletion of the dopamine neurons in a region known as the substantia nigra causes a multitude of symptoms. The most notable of these symptoms include tremors, slowed movement, memory difficulties and behavioural changes.

Parkinson’s clinical trials are one of the most challenging areas of research with a lack of therapeutics achieving desired disease modification. One of the major causes for treatment failing to progress to market is the placebo effect.

The patients’ desire to retain independence and basic functions means that the placebo effect reduces symptoms even beyond experimental treatment. As a result, drugs fail to achieve the end-point as the observed improvements are primarily psychological and outweigh the efficacy of the drug.

Gene therapy

Over the last decade, Parkinson’s research has shifted towards cell and gene therapy (CGT). Current treatment is designed to replace the dopamine lost in the brain which, long-term, causes a multitude of side effects and does not modify the disease.

Gene therapy is a broad term which covers methods that improve the genetic profile of an organism by “means of the correction of altered (mutated) genes or site-specific modifications that have therapeutic treatment as target”.

The introduction of gene therapy for Parkinson’s has been split into possible targets classed as disease-modifying or non-disease modifying. Disease modifying strategies revolve around stopping PD-mediated cell death and/or regenerating lost neurons.

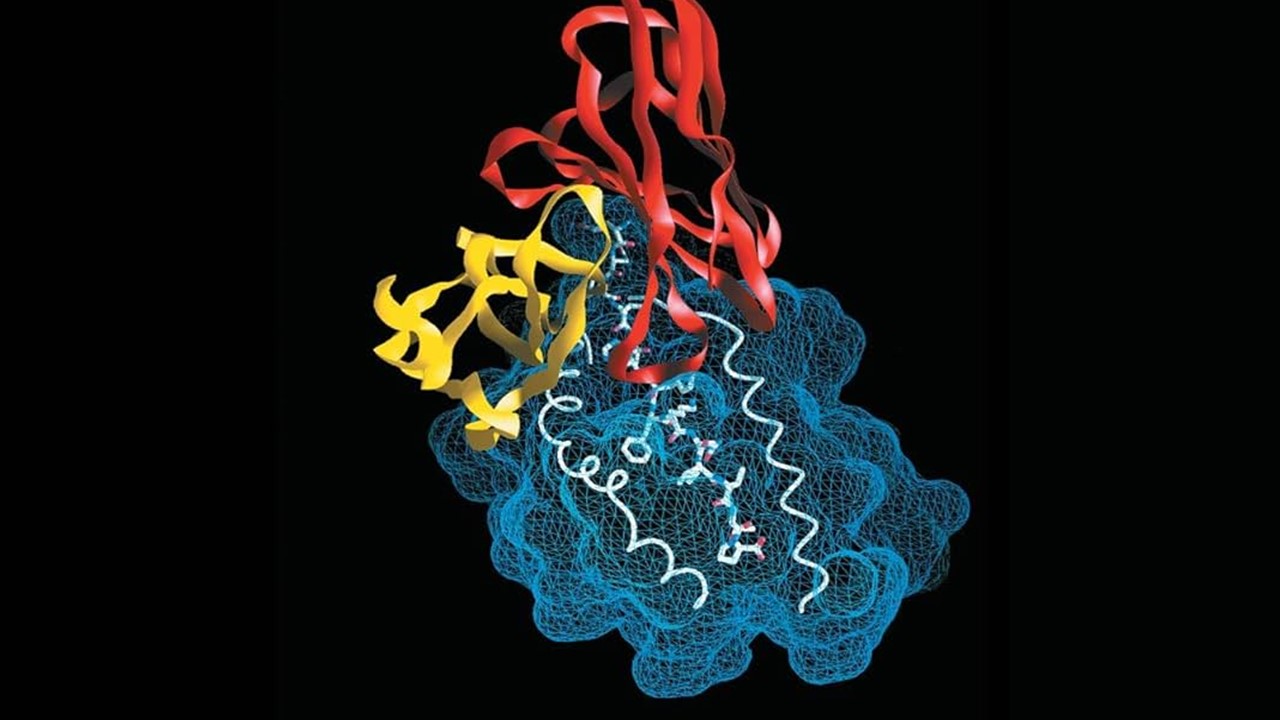

Previous Parkinson’s clinical trials of CGT have been based on viral vectors to deliver therapeutic transgenes to neurons within the basal ganglia. This delivery system remains a popular choice in the field and at the forefront of gene therapy.

Bayey has initiated a gene therapy unit through Asklepios Biopharmaceutical which is currently recruiting patients for a phase 1b trial of a gene therapy using an adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector. This delivery system is designed to “deliver a gene for human glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) into the neurons in the putamen”. GDNF is a naturally occurring protein in the body, previously shown to support the growth, survival, and maturation of dopaminergic neurons. This supports the rationale of delivering GDNF which could stimulate the growth of dopaminergic neurons and recover the loss of dopaminergic signalling which is essential for symptom recovery.

Stem cell therapy

BlueRock Therapeutics, a subsidiary of Bayer Pharmaceutical is utilising an alternative approach for Parkinson’s CGT. According to a recent industry article,” in the BlueRock trial the first patient has been administered the first dose of pluripotent stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons – MSK-DA01. The drug was delivered via surgical transplant procedures into the putamen area of the brain”.

Pluripotent stem cells are cells that have the capacity to self-renew and develop into any cell of the adult body. By dividing and developing into the three primary germ cell layers of the early embryo, pluripotent stem cells can differentiate into any tissue type.

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived dopaminergic (DA) neurons have remained at the forefront of Parkinson’s CGT research. Midbrain dopaminergic neurons can be efficiently induced from human embryonic stem cells and iPSCs and, when grafted into the target brain region, can improve the impaired behaviour of rodent and non-human primate (PD) models.

The success of preclinical studies supporting the efficacy of stem cell transplantation for dopaminergic restoration in PD models has played a huge part in accelerating clinical studies of CGT in humans.

Potential CGT challenges – delivery system

The delivery system of CGT varies across the pharmaceutical industry, but is usually divided into viral- and non-viral vectors. Traditional viral vector-based gene therapy is achieved by in vivo delivery of the “therapeutic gene into the patient by vectors based on retroviruses, adenoviruses (ADs) or adeno-associated viruses (AAV)”.

The ideal delivery system for gene therapy in the central nervous system (CNS) will aim to follow a specific criteria: (1) minimally invasive delivery (2) target specific tissue (3) achieve long-life treatment following a single, low dose. One of the main obstacles for gene therapy in the CNS is the blood brain barrier (BBB).

As a protective measure, the BBB prevents the diffusion of drugs (delivered intravenously) into the brain. This was a particular issue raised for AAV vectors, highlighted in a journal review. However, direct delivery into the CNS is one method of bypassing the BBB. This appears to be the direction for Bayer’s gene therapy, which will be administered directly into the putamen region.

This is known as an intraparenchymal injection, and a number of preclinical studies have demonstrated successful circumvention of the BBB. There are, of course, a number of challenges with this method of viral vector gene delivery highlighted in the aforementioned review:

- This method is highly invasive which may not be an appropriate method for clinically vulnerable patients who may find this distressing

- Previous studies have demonstrated the distribution of AAV particles within the brain (of higher order animals) is restricted

- Intracranial delivery is correlated with a lower probability of therapeutic efficacy in larger mammals

For CGT, one of the greatest barriers is the immune system, which could attack the stem cells/genes delivered into the brain. For AskBio’s gene therapy, this is a potential risk. Humoral immune responses, derived from antibody-producing B cells, can develop against AAV. Humoral immunity refers to antibody-mediated immune responses. This is also a challenge for BlueRock Therapeutics stem cell therapy, in which the transplanted cells will be destroyed by the immune system as a protective mechanism against foreign bodies.

However, the transition from preclinical to Bayer’s clinical trials infers that there is potential for success and safety for both cell and gene therapy. The phase one trial for Bayer’s stem cell therapy “primarily examines the safety and tolerability of cell transplantation a year after the procedure. Secondary goals include assessing evidence of cell survival following transplant and motor effects one and two years after surgery”. In other words, this will determine the efficacy of the delivery system with regards to symptom improvement and highlight any potential safety issues.

These clinical trials represent a huge milestone in Parkinson’s research. For the first time, there is potential to develop therapies which could overcome the short-lived efficacy and extensive side effects of current Parkinson’s treatment. For a significantly unmet clinical need, this could offer a hope for a growing patient population. Furthermore, successful disease modification within these CGT trials could potentially lead to the development of CGT for other diseases of the CNS.

- thus specific gene expression silencing is obtained

siRNAs have been described as the most promising type of RNA-based therapeutic oligonucleotide drug. The ability to inactivate RNA molecules in a sequence-specific reinforces potential for precision medicine in specific RNAi therapies.

One of the main advantages of siRNAs over small molecules and monoclonal antibody drugs is the simpler execution of function. siRNAs work by complete Watson-Crick base pairing with mRNA, whereas small molecule and monoclonal antibody drugs need to recognise the complicated spatial conformation of certain proteins.

As a result, there are many diseases, especially rare forms, that are not treatable by small molecule and monoclonal antibody drugs due to the complexity of the pathology in which a target molecule with high activity, affinity and specificity cannot be identified.

Despite this significant advantage, there remain a number of barriers for siRNA to their targets. Firstly, siRNAs are unable to directly penetrate the cell membrane and can enter the cell only by endocytosis or pinocytosis. However, in order to implement the silencing effect, siRNA must penetrate the membrane and exit into the cytoplasm.

When siRNA enters the cytoplasmic space via endo/pinocytosis, there is also a risk it will be cleaved by cytoplasmic ribonucleases or its concentration can decrease due to the division of target cells. This is an obvious issue when it comes to optimising the bioavailability of the drug for two reasons: (1) concentration is affected by internal cellular mechanisms, and 2) is susceptible to degradation by enzymes.

The high specificity of action which makes siRNA so desirable can also cause off-target effects. As a result this limits its use in high concentrations due to the induced toxicity. The most significant non-targeted effect of siRNA is unwanted activation of the system of innate immunity under the action of certain motifs in the siRNA sequence.

Fortunately, research in this area has led to chemical modifications that may affect the properties of siRNA.

One of the most saturated areas of interest is the use of bioconjugates, like with ASOs, which enables a more direct delivery system to target cells. A stable linker binding siRNA and biomolecules together prevents a decrease in the efficiency of RNAi associated with the inhibition of RISC assembly. Lipids and cholesterol were some of the first ligands suggested for conjugation with siRNAs as they can overcome the issue of the hydrophobic cell membrane barrier.

On-going research is determined to address some of the challenges with siRNAs and ASOs through chemical modifications to improve bioavailability and reduce toxicity. Despite these challenges, the efficacy of these drugs remains evident with an increasing number reaching the market. The end goal is optimise the delivery of these drugs to the point where they can be potentially developed for effective precision therapeutics.

Charlotte Di Salvo, Lead Medical Writer

PharmaFeatures

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Cell & Gene Therapy

Eyeing the Future: Stem Cells and the Promise of Corneal Restoration

By reducing dependency on donor tissues and minimizing immunosuppressive demands, iCEPS has the potential to redefine LSCD treatment.

Cell & Gene Therapy

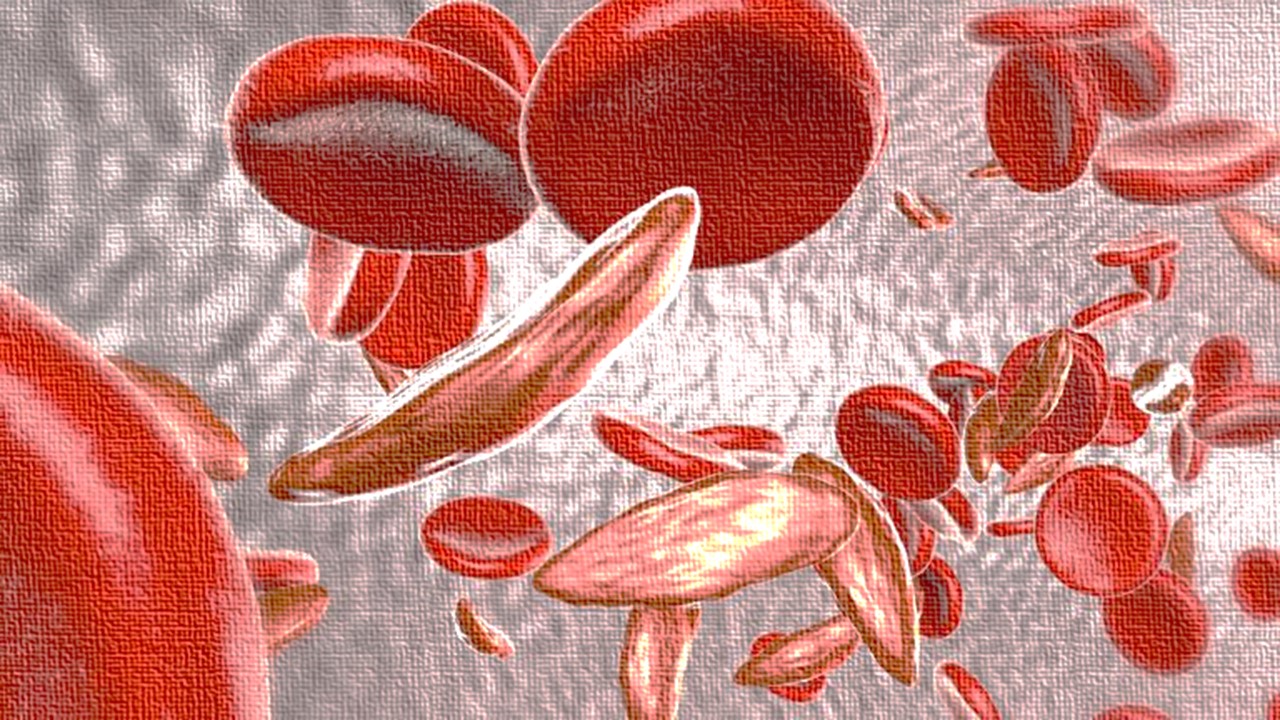

A Cure in the Code: How Gene Editing is Transforming the Fight Against Sickle Cell Disease

BIVV003’s success highlights gene editing’s potential to treat genetic disorders at their root, offering hope for other conditions.

Read More Articles

Aerogel Pharmaceutics Reimagined: How Chitosan-Based Aerogels and Hybrid Computational Models Are Reshaping Nasal Drug Delivery Systems

Simulating with precision and formulating with insight, the future of pharmacology becomes not just predictive but programmable, one cell at a time.

Coprocessed for Compression: Reengineering Metformin Hydrochloride with Hydroxypropyl Cellulose via Coprecipitation for Direct Compression Enhancement

In manufacturing, minimizing granulation lines, drying tunnels, and multiple milling stages reduces equipment costs, process footprint, and energy consumption.

Decoding Molecular Libraries: Error-Resilient Sequencing Analysis and Multidimensional Pattern Recognition

tagFinder exemplifies the convergence of computational innovation and chemical biology, offering a robust framework to navigate the complexities of DNA-encoded science