Decoding Disease Mechanisms with Microphysiological Systems

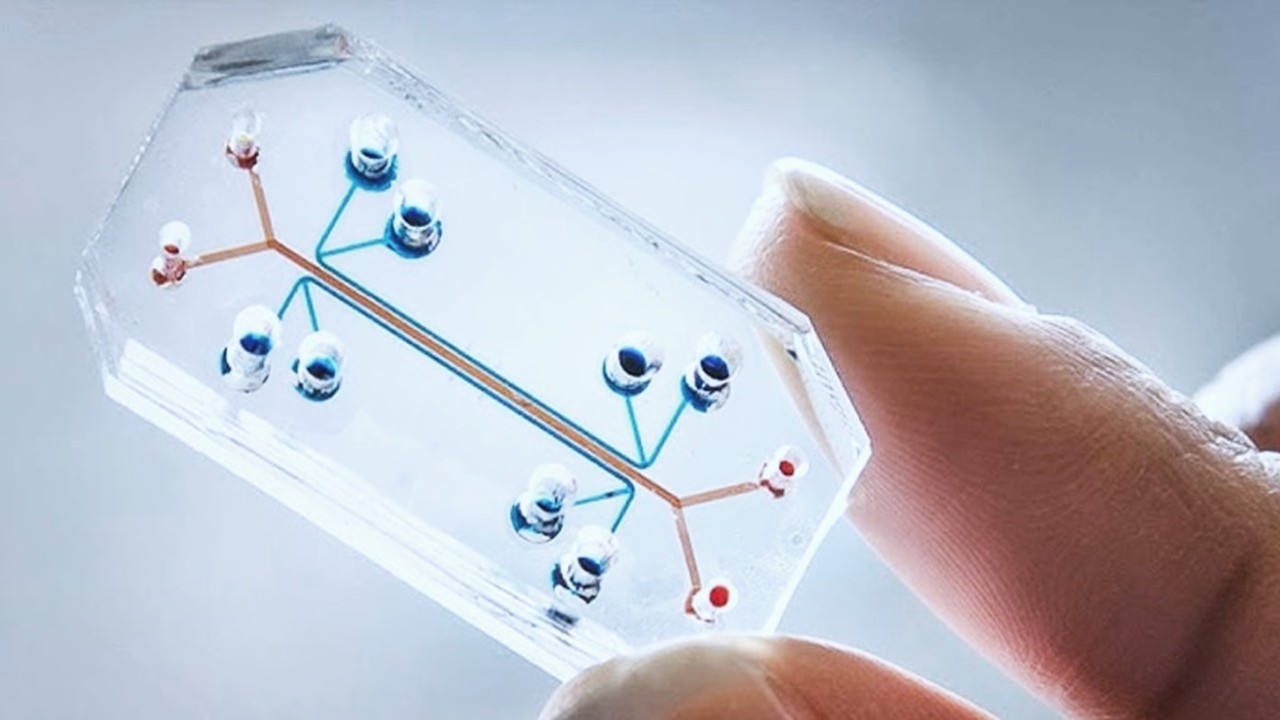

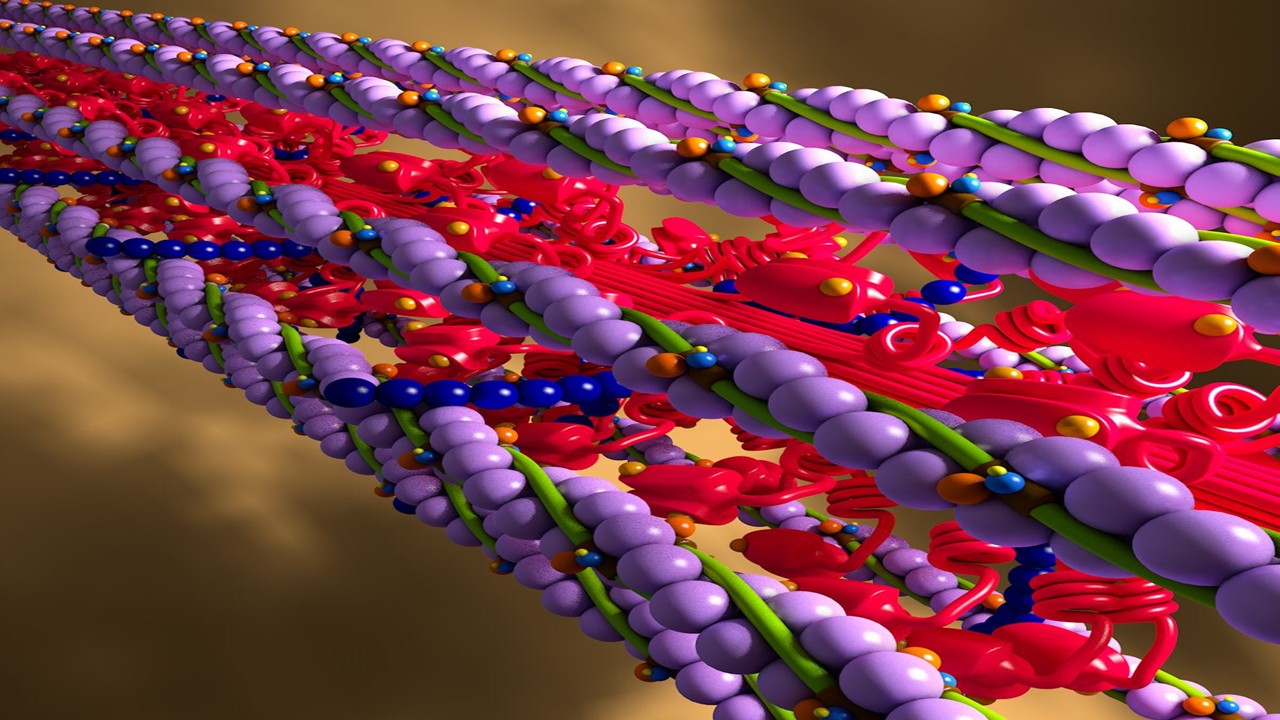

The advent of organ-on-a-chip platforms has transformed the study of human physiology and pathology by replicating dynamic tissue microenvironments. Unlike static 2D cell cultures, these systems incorporate microfluidic channels, mechanical forces, and multicellular architectures to emulate organ-level functions. For example, a neurovascular unit chip modeling the blood-brain barrier demonstrated time-dependent recovery of barrier integrity after inflammatory stimulation, alongside cytokine activation and metabolomic pathway alterations. Such platforms enable researchers to dissect disease-specific molecular signatures, such as smoke-induced ciliary dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) models, where bronchiolar epithelium from COPD patients revealed unique transcriptional responses. These insights are critical for identifying translatable biomarkers that inform clinical trial endpoints, such as hemodynamic changes in pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) further enhance the translational relevance of these models. In Barth syndrome, iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes harboring tafazzin mutations exhibited metabolic and structural defects, which CRISPR-Cas9 editing confirmed as causative. This approach enables personalized disease modeling, capturing interindividual variability in drug responses and disease progression. By integrating genetic, metabolic, and functional data, microphysiological systems bridge the gap between in vitro experimentation and clinical pathophysiology, offering a platform to study longitudinal disease trajectories.

Multi-organ chips extend this utility by simulating systemic interactions. A liver-lung interface, for instance, can elucidate how hepatic metabolites influence distal tissue function—a paradigm shift from isolated organ analyses. Such systems are particularly transformative for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases, where microenvironmental cross-talk dictates therapeutic outcomes. Researchers emphasize that these platforms are not merely incremental improvements but foundational tools for mechanism-driven drug development, enabling hypothesis testing in human-relevant contexts.

The Coalition Against Major Diseases (CAMD) has leveraged similar models to qualify drug development tools for Alzheimer’s, incorporating disease progression and dropout patterns into clinical trial simulations. By aligning preclinical findings with clinical endpoints, microphysiological systems reduce reliance on animal models, which often fail to predict human responses. This alignment is critical for rare diseases, where patient populations are small, and trial design must maximize efficiency.

Regulatory agencies now recognize these systems as vital for advancing model-informed drug development (MIDD). The FDA’s Office of Clinical Pharmacology (OCP) prioritizes quantitative clinical pharmacology models that integrate microphysiological data to optimize dosing regimens and predict subpopulation variability. Such models are increasingly used to design delayed-start trials in Parkinson’s disease, where distinguishing disease-modifying effects from symptomatic relief requires precise biomarker validation.

Pharmacology Reimagined: Target Validation and Lead Optimization

Microphysiological systems are redefining early-stage drug discovery by enabling functional validation of therapeutic targets in human-relevant environments. A brain slice-on-a-chip platform demonstrated target engagement for glutamate receptor antagonists, suppressing spontaneous electrical activity in neural networks—a feat unachievable in conventional cultures. These systems are indispensable for rare diseases, where animal models are scarce; for example, a microfluidic model of pediatric pulmonary arterial hypertension identified hemodynamic biomarkers that informed phase 3 trial endpoints.

Lead optimization benefits from organ chips’ ability to replicate pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) relationships. Liver-on-a-chip platforms maintain cytochrome P450 activity for weeks, allowing chronic toxicity studies and metabolite profiling. In one study, troglitazone’s delayed hepatotoxicity and immune-mediated liver injury from trovafloxacin were replicated, highlighting their utility in predicting idiosyncratic reactions. These platforms also evaluate drug efficacy in genetic contexts, such as iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from arrhythmia-prone patients, which screen for compound-specific cardiotoxicity.

The integration of multi-organ systems enables systemic PK-PD modeling. A liver-kidney chip revealed nephrotoxicity from ifosfamide metabolites generated hepatically, illustrating how inter-organ crosstalk informs toxicity mechanisms. Such models are vital for biologics and biosimilars, where batch-to-batch variability necessitates rigorous functional testing. By correlating in vitro efficacy with clinical outcomes, organ chips reduce attrition in late-stage trials.

Patient stratification is another frontier. Chips using cells from diverse genetic backgrounds can predict population-specific responses, guiding inclusion criteria for clinical trials. For example, a gut-on-a-chip with Crohn’s disease-derived epithelial cells identified mucosal repair mechanisms, informing targeted therapies. This precision aligns with the FDA’s emphasis on individualized dosing, particularly in oncology, where tumor-on-a-chip models test combination therapies in genomically defined contexts.

Despite their promise, challenges remain in standardizing protocols across labs. Variability in cell sources, scaffold materials, and fluidic parameters complicates data reproducibility. Initiatives like the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) are addressing these gaps through consortium-driven validation studies, ensuring organ chips meet regulatory standards for preclinical data submission.

Toxicology Redefined: Mechanistic Insights and Off-Target Prediction

Organ-on-a-chip technologies are advancing toxicology by elucidating mechanisms of on- and off-target toxicity. A four-cell liver model recapitulated troglitazone’s biphasic toxicity—acute injury at high doses and delayed mitochondrial dysfunction at therapeutic concentrations. This system also modeled immune-mediated hepatotoxicity from trovafloxacin, implicating cytokine release in Kupffer cells. Such granularity surpasses traditional hepatocyte assays, which lack non-parenchymal cell interactions.

Multi-organ platforms reveal secondary toxicities from metabolite exposure. A liver-kidney chip demonstrated aristolochic acid’s nephrotoxicity via hepatic nitroreduction and tubular uptake via organic anion transporters. Similarly, a lung-liver interface modeled inhaled drug metabolism, identifying reactive metabolites that induce pulmonary fibrosis. These systems are particularly valuable for oncology, where chemotherapeutics often damage off-target organs; a cardiac chip with iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes predicts anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, guiding dose optimization.

Microphysiological systems also address reproductive and developmental toxicity. A placenta-on-a-chip models nutrient and drug transport across the placental barrier, predicting fetal exposure to teratogens. This is critical for drugs like valproate, where animal models poorly predict human risk. Similarly, a blood-testis barrier chip assesses chemotherapeutic penetration into gonadal sanctuaries, informing fertility preservation strategies.

Regulatory acceptance of these models is growing. The FDA’s PBPK guidance now encourages in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) using organ chip data, particularly for DDI risk assessment. A kidney tubule chip, for instance, quantified cisplatin uptake via OCT2 transporters, informing clinical management of nephrotoxicity. Such applications align with PDUFA VI goals to enhance predictive toxicology tools, reducing post-market safety withdrawals.

Challenges persist in modeling chronic toxicity and immune responses. While liver chips sustain function for 28 days, longer-term studies are needed for drugs with cumulative effects. Incorporating immune cells into chips, such as a lymph node-on-a-chip with T-cell activation, could improve immunotoxicity prediction. These innovations will solidify organ chips as cornerstones of preclinical safety assessment.

PBPK Modeling Enhanced: ADME Parameters from Organ Chips

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models require accurate absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) parameters, which organ chips are uniquely positioned to provide. Gut-on-a-chip systems mimic intestinal peristalsis and epithelial polarization, yielding permeability data that better predict human absorption. A microfluidic Caco-2 model showed higher apparent permeability for caffeine and atenolol than static transwells, attributed to microvilli formation under flow. These findings underscore the need to recalibrate in vitro-in vivo correlations using dynamic models.

Liver chips refine metabolic clearance predictions. Primary hepatocyte-based platforms maintain CYP3A4 and UGT activity for weeks, enabling chronic DDI studies. In one case, lidocaine clearance data from a liver chip populated a PBPK model that accurately predicted human PK. This approach is superior to suspended hepatocytes, which lose metabolic competence within hours. Co-culture with Kupffer cells further captures cytokine-mediated enzyme modulation, relevant for inflammatory conditions.

Distribution kinetics, historically extrapolated from animal data, are now explorable via multi-organ chips. A liver-brain model predicted trimethylamine N-oxide’s BBB penetration, later confirmed in vivo. Such systems address perfusion-limited distribution, a major gap in traditional PBPK models. Future kidney chips may quantify tubular secretion and reabsorption under physiological flow, refining renal clearance predictions.

Excretion studies benefit from advances in kidney-on-a-chip technology. A proximal tubule model with primary cells expressed OCT2 and MATE transporters, enabling cisplatin uptake and toxicity studies. While current systems only model nephron segments, integrating glomerular and tubular compartments could replicate full renal physiology. This would aid drugs like metformin, whose renal clearance involves complex transporter interplay.

The future lies in linked organ systems. A “physiome-on-a-chip” with liver, kidney, and gut compartments characterized diclofenac’s PK, including enterohepatic recycling. Such platforms could replace animal PK studies, aligning with the 3Rs (replacement, reduction, refinement) principles. Standardizing these systems for regulatory use requires collaborative validation, as seen in the IQ Consortium’s microphysiological systems working group.

Overcoming Technical Hurdles: Standardization and Scalability

The translational potential of organ chips hinges on overcoming technical variability. Differences in cell sources (primary vs. iPSC-derived), scaffold materials (PDMS vs. hydrogels), and fluid shear stress complicate cross-study comparisons. A lung-on-a-chip using primary alveolar cells may yield different cytokine profiles than one with iPSC-derived epithelium, affecting toxicity predictions. Standardized protocols, such as those developed by the Tissue Chip Testing Centers, are addressing these inconsistencies.

Scalability is another barrier. High-throughput screening requires miniaturized arrays of organ chips, yet maintaining sterility and cell viability in 96-well formats is challenging. Recent advances in automated liquid handling and sensor integration (e.g., transepithelial electrical resistance monitoring) are improving throughput. For example, a liver-chip array screened 100 compounds for steatosis potential in a week, a task impossible with traditional models.

Long-term culture stability remains elusive for some systems. While liver chips sustain function for a month, neuronal networks degrade within weeks. Incorporating vasculature-like endothelial networks improves nutrient/waste exchange, extending viability. A cardiac chip with perfusable microvessels maintained contractility for 30 days, enabling chronic cardiotoxicity studies.

Regulatory validation is progressing slowly. The FDA’s Emerging Technology Program collaborates with developers to qualify organ chips for specific contexts, such as nephrotoxicity screening. However, achieving broad acceptance requires demonstrating superiority over existing models. A multi-center study showed liver chips predicted clinical hepatotoxicity with 87% accuracy versus 50% for rodent models, a compelling case for regulatory adoption.

Economic factors also influence adoption. Organ chips are cost-prohibitive for many academic labs, though consortium-based sharing (e.g., EU-ToxRisk) mitigates this. As commercialization accelerates (e.g., Emulate’s commercial platforms), costs are expected to drop, democratizing access. Partnerships with CROs will further integrate organ chips into routine preclinical workflows.

Regulatory and Clinical Integration: Toward Precision Medicine

The FDA’s Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) initiative prioritizes organ chips for addressing clinical pharmacology questions. These platforms inform dosing regimens by simulating drug exposure in subpopulations—e.g., hepatic impairment models predicting PK shifts for renally cleared drugs. A rheumatoid arthritis synovium-on-a-chip tested JAK inhibitors across cytokine gradients, guiding dose titration for genetically stratified patients.

Pediatric drug development benefits uniquely. A lung-on-a-chip with immature alveolar cells modeled surfactant deficiency, optimizing dosing for preterm neonates. Similarly, a blood-brain barrier chip with pediatric-derived cells assessed morphine penetration, informing neonatal analgesia protocols. These applications align with the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA), emphasizing non-animal models for pediatric studies.

In oncology, tumor-microenvironment chips test immunotherapies’ efficacy. A melanoma-on-a-chip with autologous T-cells and stromal cells revealed PD-1 inhibitor resistance mechanisms, guiding combination therapy design. Such models are invaluable for biosimilars, where functional comparability must be demonstrated without large clinical trials.

Global regulatory harmonization is critical. The ICH M7 guideline now accepts organ chip data for genotoxicity risk assessment, reducing redundant testing. Similarly, the EMA’s qualification opinion on a kidney tubule chip for DDI studies signals growing international acceptance. These strides underscore organ chips’ role in fulfilling PDUFA VI goals to expedite drug development.

Looking ahead, organ chips will enable “clinical trials on a chip,” where patient-derived cells predict individual responses. A colorectal cancer chip using biopsy-derived organoids tested cetuximab efficacy, correlating with patient outcomes. This approach could revolutionize personalized medicine, minimizing trial-and-error prescribing. As regulatory frameworks evolve to embrace these innovations, organ chips will become indispensable in achieving safer, more effective therapies.

Study DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12627

Engr. Dex Marco Tiu Guibelondo, B.Sc. Pharm, R.Ph., B.Sc. CpE

Editor-in-Chief, PharmaFEATURES