David Cook is the Chief Scientific Officer at Blueberry Therapeutics, a UK pharmaceutical company specializing in the treatment of dermatological disorders. Dr. Cook has an extensive background throughout the pharma industry – with a particular focus on safety and data science across a plethora of therapeutic areas. We caught up with him to discuss his current work on skin disease and drug discovery.

PF: It’s such a pleasure to have you with us today, Dr. Cook. You have an incredibly well-rounded background across a wide breadth of the life sciences – from biochemistry, to work on viruses, oncology, clinical safety, systems biology – to mention just a few. What would you say was the common denominator that motivated you throughout these fields? Are there any particular highlights you would like to share with us?

DC: I would say the core value for me – the value that motivated me towards a career as an industrial scientist – is the idea of providing a direct benefit to patients, and society at large. It may sound like a cliche, and that the pharma industry may yet have progress to make in salvaging its reputation and image. But, in my experience, we are all motivated by the idea that we are helping someone, and that we are leaving the world a better place than we found it – whether it be tackling a severe chronic disease such as cancer, or something less severe but that still affects so many, such as athlete’s foot. Ensuring my work has a positive impact is the main driver for all the jobs and positions I have held throughout the industry. My desire is to ensure we perform better for our patients and answer the hard questions of how to bring new medicines to market. As for highlights, there have been numerous – some of which I am not at liberty to mention at present, sadly. One of the more recent ones, within the context of Blueberry, would be getting our first drug into the clinic, and currently to Phase II, and the biotech experience in general. Perhaps the reason it feels like such a highlight is because of how profound the experience has been in allowing me to tap into the full breadth of my background and knowledge – and putting that to use.

PF: You currently work with Blueberry Therapeutics, a UK company specializing in drug discovery and early development for dermatological treatments. What makes skin disease a unique therapeutic area to focus on?

DC: A really good question – and personally, I believe there are a few characteristics unique to skin disease. The skin is an organ, and one we have direct access to – which makes bioavailability simpler, especially when considering topical applications. This opens up opportunities and avenues for research that may not be available for other diseases where drug delivery to specific, less accessible tissues will be a challenge. This change in thinking was something I had to personally adjust to myself – particularly considering how I had come from a small-molecule oral treatment background; there were many learning experiences to be had as I transitioned. One of the other unique features of dermatological disease is often their visibility and exposure – we may think of acne and eczema as clinically mild. But if such conditions are readily apparent because they are on someone’s face, or a body part that is closely associated with our personal expression, the disease must be considered significant. Although dermatology rarely deals with life-threatening disease, the importance of the field is not to be discounted in improving our mental well-being and overall quality of life. I think that is also part of why I enjoy working in the field – the impact you have in making someone feel more confident and comfortable with themselves is immediately clear and satisfying.

PF: Blueberry works with a variety of product candidates – including biologics, peptides and small molecules; one could say it is far more united by its focus on its specialist therapeutic area than modality. Are there other modalities you would like to expand to, or do you think there is better value in honing in on the administration of these therapeutics – such as with your nanoparticle technology to optimize delivery mechanisms?

DC: You are right, we are primarily a dermatology company using innovative technology to improve treatments. We are relatively agnostic to the active ingredient and its class. We will follow whatever we think the most reliable and proven technologies are, to provide the best treatments for skin disease. Currently, this is taking us in the direction of new nanoformulation and complex nanoparticles to improve the delivery and efficacy of existing active ingredients. Our current portfolio does contain more small molecules than anything else, but it also includes peptides and larger molecules. The success of antibody therapies from other areas of the life sciences is only just spilling over into dermatology, and there is growing interest around them. We expect successful antibody therapies for conditions such as atopic dermatitis, and we see developments throughout the possible drug modalities for skin disease. So, I would not say that we feel there are any drug modalities we are particularly missing from our portfolio – but we also remain open to experimenting and investigating any possible treatment route; if it works, we will definitely look to see if improvements in formulations and delivery can be made. That is perhaps what best describes our modus operandi as a business.

PF: Do you think your unique Nanocin technology, or similar techniques, could be expanded to other therapeutic modalities – particularly ones that struggle with bioavailability?

DC: Well, I would confidently say yes, although our current focus is dermatologic conditions – the whole field of nanomedicines and complex medicines is rapidly expanding. We can see this with current health emergencies – for example, the COVID vaccines are all built on complex formulation forms, particularly the mRNA vaccines. They only work because they have the appropriate vehicle formulations to enable the delivery of molecules as complex, but also as fragile, as mRNA into the cell. While these are not specifically nanotechnologies, they do highlight the idea and significance of therapeutic ingredient vehicles – e.g. through the delivery of mRNA within lipid nanoparticles. But in expanding our Nanocin technologies, we need to remain mindful of the potential routes for delivery – while intravenous or topical, e.g. inhaled or gastrointestinal, delivery is possible, oral administration will be challenging for systemic exposure of our technology. Other nanomedicines could provide alternative ways to target treatments to specific tissue types and parts. As much of the innovation in nanomedicines is being driven through oncology, which is very focused on precision, targeted therapies, I expect advancements in specificity to continue improving as a matter of course.

PF: Are there any challenges you foresee having to overcome as you work to innovate novel treatments for skin diseases? How do you think these can be overcome?

DC: It is drug discovery and development – there will always be countless challenges, many of which will be unique to specific programs or broader drug classes. Of the major challenges, I would say the first one is safety: nanomedicines inherently raise safety profile concerns. Most safety concerns are driven by active ingredients in the majority of drug modalities – certainly so in the oncology space where safety profiles tend to vary. But for nanoparticles, the size of the delivery vehicle itself could have impacts throughout the body: the immune system may perhaps see entities of a certain size as viruses, for example. Some concerns may only be relevant to systemic, rather than topical, delivery and they may prove to be unfounded, but it is an area that needs to be addressed. The other challenge I would say needs to be overcome is the regulatory environment – and the perception of nanoparticles by regulators. This is particularly with respect to the manufacturing process of a nanomedicine – how to ensure quality and production standards, and how to communicate that to regulatory frameworks. Many innovations tend to end up having to wait for regulators to catch up with them, but the COVID-19 pandemic has definitely done a lot to accelerate this process with complex formulations.

PF: You have an involved understanding of Artificial Intelligence, and Machine Learning in particular. What impacts do you expect these technologies to have in the drug discovery and early preclinical or clinical development stages?

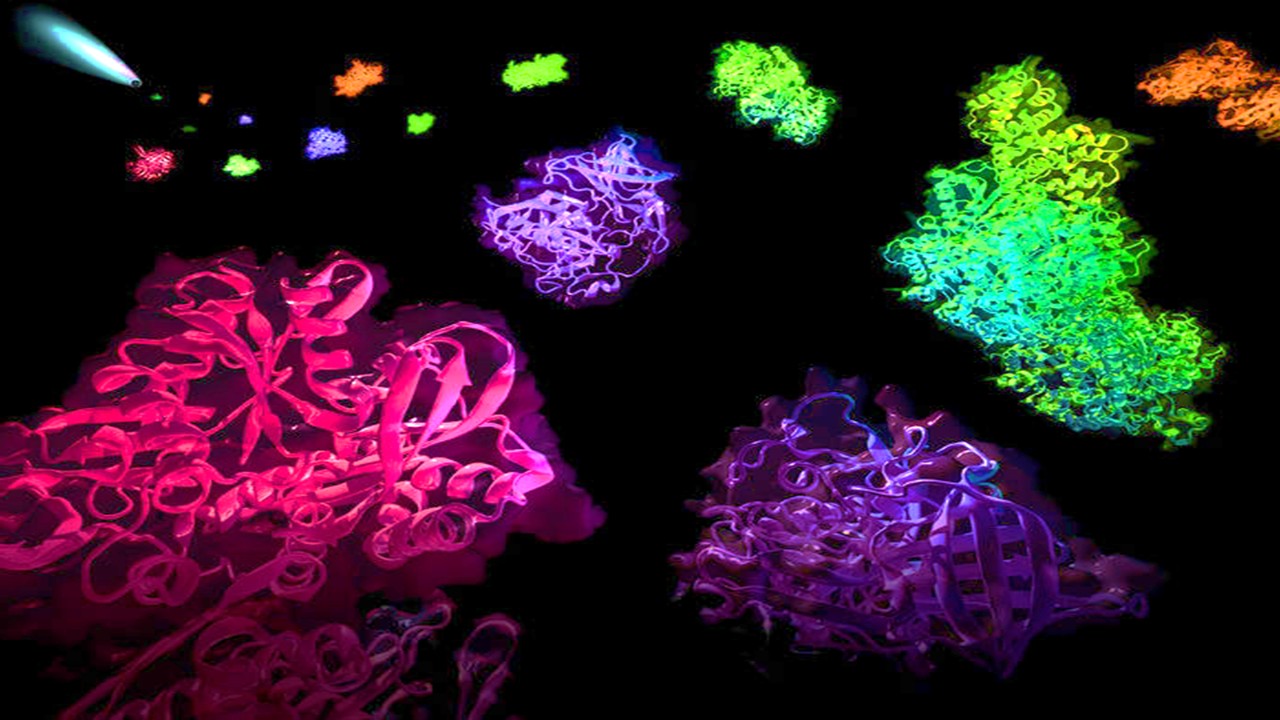

DC: A pretty challenging question there. I think AI technology holds potential for both progress and disruption, and the requirements for massive datasets to develop the algorithms to begin with present large obstacles for many companies. The same is true for the datasets we apply these algorithms too – we have a lot of standardization, harmonization and data vetting that needs to occur. We end up developing very sophisticated models, and then we apply them to such low-grade or sparse datasets – but this is often because there is still so much we do not know about biological systems and disease pathology. I do foresee AI making its first transformative impacts in drug discovery in areas with rich, high-quality data – and that is where we see the technology being deployed right now. This includes areas such as structure-activity relationships, understanding large chemical libraries, pharmacokinetics, drug metabolism. These areas involve few dimensions with excellent data, or enable machine learning to truly show their potential for training-based decision-making. When it comes to clinical development, there is an entire world to be discovered – improving patient selection, predicting treatment responses, etc. AI can truly revolutionize this area, but we require much better datasets with fewer heterogeneities before we can truly apply pioneering models to the space.

PF: Particularly for modalities with small datasets, such as the treatments Blueberry is investigating, do you foresee any unique challenges with regards to AI adoption and utilization? Are there other AI implementations – such as neural networks – that you think may work better in the long term?

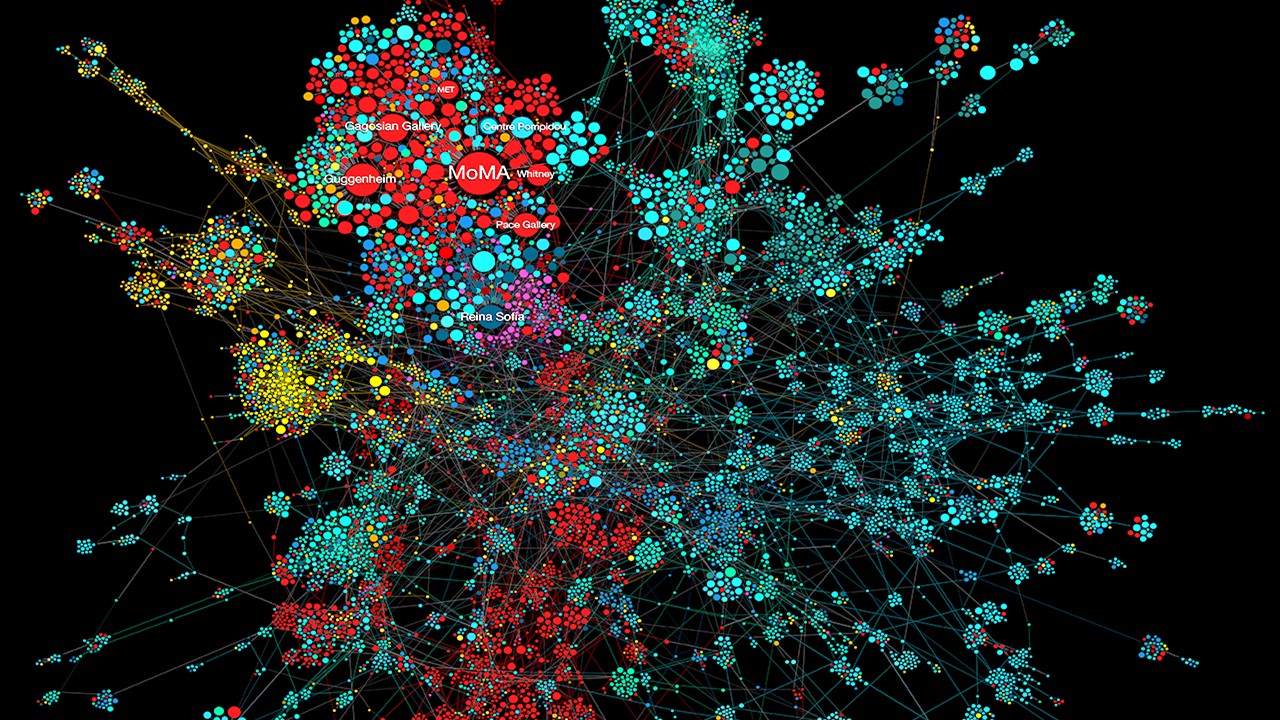

DC: Another excellent question – but it does come back to the limited datasets, which is one of the challenges we face with clinical development endeavors. This is true even for Phase III developments. I think one of the best steps ahead would be to contextualize the datasets we do have, no matter how small, with the broader real-world population. While this may be a challenge, AI does hold the potential to draw much better conclusions through these comparisons – especially in its ability to place data in context. One could say we often do not know we are measuring “the important thing” unless we already know it is “the important thing” – AI could ameliorate that challenge. However, I would not consider myself enough of an expert to be able to tell you whether one AI methodology may outperform the other and for which task – whether that be machine learning or neural networks. This does bring us to another challenge moving forward however – that we have to get very dissimilar types of people, from different backgrounds, to work together: computer scientists and disease experts. Forming multidisciplinary teams to traverse uncharted waters may be exciting, but it also requires a lot of work, time and resources before we can get it right. And, naturally, to solve these deficiencies, we must also add computer scientists and bioinformaticians to the core of our drug discovery and development teams – they bring invaluable viewpoints that will be critical for the integration of these disruptive technologies in our pipelines.

PF: You will be facilitating a similar conversation in Proventa International’s Bioinformatics Strategy Meeting in London 2022. Are there any other insights you would like to share with us prior to the event? Do you look forward to the resumption of face-to-face scientific discussions?

DC: We have mostly covered the entire breadth of topics I would like to expand upon – the data, the importance of how that data is generated, and the new technologies. We recognize the importance of AI, and all its implementations, and its potential to offer strong contextualizing analyses. Seeing how the technology is implemented and deployed properly remains one of the most important subjects in our field – and one that is worth further discussion. I think one of the best things to come from these conferences is how they often bring scientists together from disciplines that do not often interact – which allows them to truly communicate about what they need from each other. I am absolutely looking forward to the return of face-to-face events and the ability to exchange ideas up close – while virtual conferences do provide a good replacement, they cannot substitute the physical experience. The physical experience provides so much more opportunity for discourse and the possibility for new partnerships and projects to emerge through dialogue. Naturally, I am also simply anticipating hearing about the new developments in the field, particularly the computational side of things; I feel the pandemic has taken a toll on how well-connected each of us really is anymore.

Tuğçe Freeborough-Gerrard, Producer, Proventa International

Nick Zoukas, Former Editor, PharmaFEATURES

Join Proventa International’s Bioinformatics Strategy Meeting in London to hear more about the growing tech revolutions within the life sciences – from multi-omics, AI, quantum computing, and others – the pace of innovation is unabating. Meet key stakeholders and participate in closed door roundtable discussions for topics on the bleeding edge of Bioinformatics, facilitated by world-renowned experts

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Interviews

Setting the Benchmark: Shaping Analytical Standards to Accelerate Global Convergence in Biologics Quality Systems with Stephan Krause, Bristol Myers Squibb

About the Interviewee Stephan O. Krause is the Executive Director of Cell Therapy Global Quality of Bristol Myers Squibb. Stephan O. Krause, Ph.D., serves as Executive Director for Analytical Science and Technology in Cell Therapy Quality at Bristol Myers Squibb, where he leads global analytical and quality functions supporting the development, manufacture, and regulatory advancement […]

Interviews

Harmonizing Biologics Transfer: Global Regulatory Strategy, Compliance Best Practices, and Operational Alignment with Gopi Vudathala, Incyte Corporation

About the Interviewee Gopi Vudathala is the Global Head of Regulatory Affairs and Chemistry, Manufacturing and Controls at Incyte Corporation. Gopi Vudathala, Ph.D., serves as the Global Head of Regulatory Affairs and Chemistry, Manufacturing and Controls (CMC) at Incyte Corporation, a biopharmaceutical company dedicated to the discovery, development, and commercialization of proprietary therapeutics across oncology […]

Interviews

Redefining the Analytical Frontiers of Peptide Science: Innovations Shaping the Next Generation of Therapeutics with Johan Evenäs, RG Discovery

About the Interviewee Johan Evenäs is the Chief Executive Officer at RG Discovery. Johan Evenäs, Ph.D., serves as the Chief Executive Officer of RG Discovery, a life sciences company based in Lund, Sweden, specializing in drug discovery solutions including medicinal chemistry, fragment-based lead discovery, and advanced analytical services. Dr. Evenäs holds an M.Sc. in Chemical […]

Interviews

Toward Industrial Impact: Scaling the Strategic Vision for Bioprocessing Excellence with Greg Papastoitsis, Ankyra Therapeutics

About the Interviewee Gregory Zarbis-Papastoitsis is the Chief Process and Manufacturing Officer at Ankyra Therapeutics. Gregory Zarbis-Papastoitsis, Ph.D., serves as the Chief Process and Manufacturing Officer at Ankyra Therapeutics, an immuno-oncology company advancing novel intratumoral anchored cytokines currently in Phase 1 clinical trials. Dr. Zarbis-Papastoitsis holds a B.S. and Ph.D. in Biochemistry from Binghamton University, […]

Read More Articles

Myosin’s Molecular Toggle: How Dimerization of the Globular Tail Domain Controls the Motor Function of Myo5a

Myo5a exists in either an inhibited, triangulated rest or an extended, motile activation, each conformation dictated by the interplay between the GTD and its surroundings.

Designing Better Sugar Stoppers: Engineering Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors via Fragment-Based Dynamic Chemistry

One of the most pressing challenges in anti-diabetic therapy is reducing the unpleasant and often debilitating gastrointestinal side effects that accompany α-amylase inhibition.