Screening methods in oncology are critical to enable doctors to detect cancer in at-risk populations. Early detection of the disease is essential to choose appropriate treatment to increase the chance of survival. The latest research identifies flaws in clinical screening methods and the pharmaceutical challenges in rolling out new methods of early detection.

The importance of screening and early detection in disease management

Across the globe, cancer screening programmes play a large part in detecting and treating asymptomatic cancer in at-risk populations. This hypothetically improves patient outcome with early detection before the prognosis becomes poor with symptomatic development in later stages. Screening is also important in the prevention of certain cancer types and treating risk factors. According to Cancer Research UK, “79% of cancers detected among women aged 50-70 through breast screening in the UK are invasive breast cancers”. This statistic supports the value of cancer screening in diagnoses which would otherwise be significantly lower without screening to detect breast cancer, a disease which can present differently across the population.

Screening is critical in early detection of pre-symptomatic cancer, when it is typically easier to treat successfully. Survival rates for some cancer types remain the same regardless of early detection. In a 2019 article, the survival rate drop for liver cancer drops from 69.1% at stage 2 to only 39.3% at stage 3. This significantly impacts the prognosis of patients with cancer types like this, in which survival rates plummet with disease progression. Early detection enables the introduction of treatment which can either slow or treat the disease, resulting in a greater chance of survival and better quality of life.

Cancer screening: A clinical challenge

Despite breast cancer representing one of the most common forms of the disease, clinical criteria for screening appears to be neglecting some patient groups. In a recent review, it was highlighted that regular breast cancer screening is typically only recommended for women in the at-risk age group, the over 50s. However, breast cancer in younger women is often more aggressive and as a result harder to treat, especially in the later stages. It has been suggested that this presents a serious disadvantage for the age group which would otherwise benefit from routine screening, a topic under debate.

Lead-time bias is also a problem across cancer screening. According to the National Cancer Institute, lead-time bias occurs when “screening finds a cancer earlier than that cancer would have been diagnosed because of symptoms, but the earlier diagnosis does nothing to change the course of the disease.” Lead time bias can lead to an overdiagnosis bias. This can occur when a non-fatal cancer is detected during screening that otherwise would have not surfaced clinically during the patient’s remaining lifetime.

A 2020 study conducted “an exploration for quantification of overdiagnosis and its effect for breast cancer screening”. After an analysis of 756,636 female breast cancer patients, they found that “23.3% of breast cancer patients diagnosed at 50−74 years old were estimated to be overdiagnosed cancers associated with regular screening”. This data emphasises the need to continue to investigate the number of overdiagnosed cancer cases vs increased survival rate as a result of screening, in order to identify whether regular screening is beneficial for a patient population relative to survival. In addition, it questions whether the screening protocols are appropriate in the case of cancers with high numbers of overdiagnosis.

Early detection: A pharmaceutical challenge

Evidence supports the need for more accurate methods of early detection, to ensure greater survival rates. However, the pharmaceutical industry often struggles to reach demand. The drug development process from lab discoveries through to implementation and clinical tests is a difficult one with a multitude of hurdles. For a new cancer test to be designed, there needs to be substantial evidence of the potential impact on cancer survival. These studies can be long and expensive, which are not always a priority in comparison to cancer treatment research.

Another problem is the poor standardisation of biological assays. Assays are an important method of defining a positive biomarker within a clinical trial that signals a cancer type. Unfortunately, the assays which define what constitutes a biomarker are not standardised across different pharmaceutical companies. This creates a significant problem when different assays are being used to quantify the presence of biomarkers. A recently published article highlighted some of the problems that arise with using multiple assays for the same biomarker, emphasising that assays “have different positive prevalence rates”. It further explains that the cause of inconsistencies is multifactorial, and include “reproducibility issues, variable antibody and assay sensitivity, even when different assays use the same antibody “. This level of inconsistency questions whether the current assay approval policies require attention to standardise assays for the same biomarker across different pharmaceutical companies.

The PanSeer assay is a prime example of an early detection method. This assay provides a preliminary early detection of various cancers up to four years prior to a conventional diagnosis. According to a 2020 Nature review, the assay “lays the foundation for a non-invasive blood test for early detection of cancer in a high-risk (or average-risk in the future) population.” With reference to another source, the article emphasises how the majority of cancer research focuses on developing therapeutic treatment, despite the fact that there are many studies which support early detection in reducing treatment cost and mortality rates. The value of early detection methods continues to be emphasised across the industry, calling for more support to develop current techniques. The Nature review echoes this and states that “to fully establish the clinical utility of PanSeer and fully validate the results of pre-diagnostic detection of cancer, we hope to proceed with a large prospective study of healthy individuals to determine if non-invasive cancer screening can reduce cancer deaths in a cost-effective manner.”

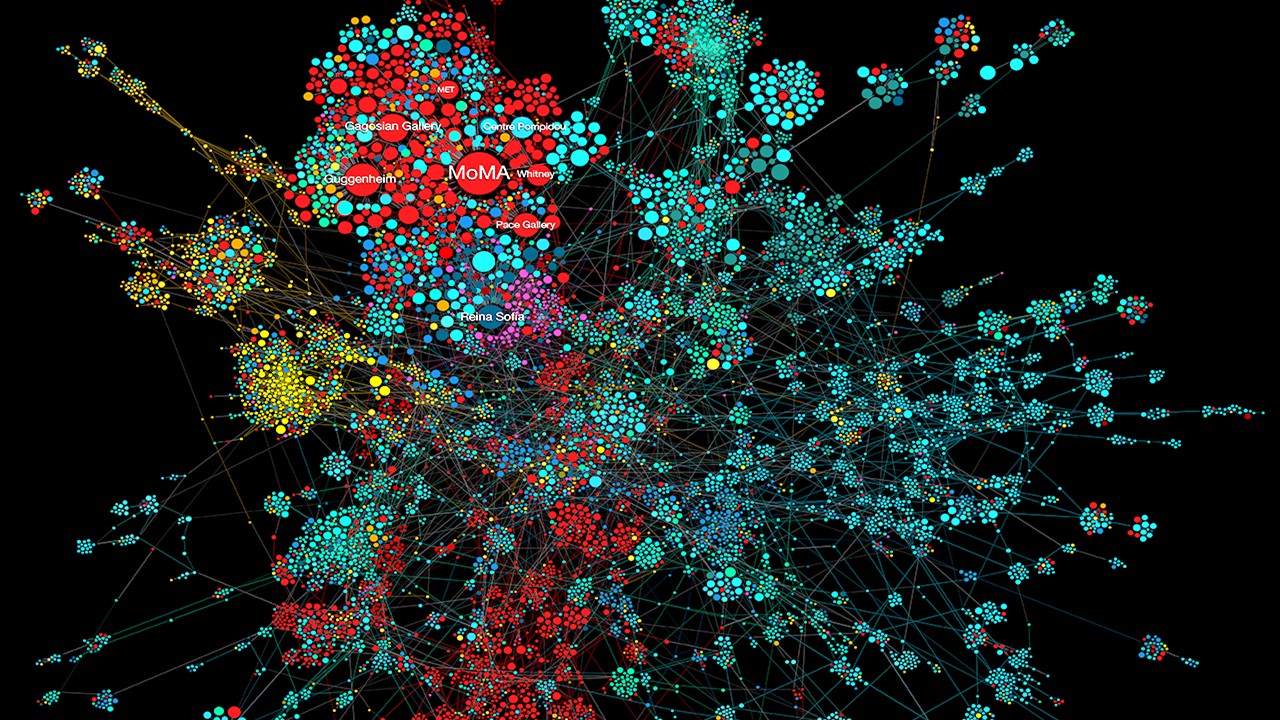

However, in 2019, the International Alliance for Cancer Early Detection (ACED) was formed to address the need for better early detection methods. The partnership is formed of Cancer Research UK, Canary Center at Stanford University, the University of Cambridge, the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute, UCL and the University of Manchester. The partnership has invested up to £55 million, which will be prioritised for the ACED to translate scientific research into (likely pharmaceutical) improvements in early cancer diagnosis.

In terms of accelerating the drug development process, the ACED hopes to improve “access to critical resources such as early disease tissue samples and longitudinal patient data”. Furthermore, the “development and use of appropriate preclinical model systems” is one of 11 key areas designated for funding. Preclinical models play a significant part in testing the safety and efficacy of drugs before humans; hence this investment represents a potential acceleration of the drug development for early cancer detection.

Charlotte Di Salvo, Lead Medical Writer

PharmaFeatures

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Clinical Operations

Beyond the Intervention: Deconstructing the Science of Healthcare Improvement

Improvement science is not a discipline in search of purity. It is a field forged in the crucible of complexity.

Clinical Operations

Cracking the Code of Clinical Change: Theories as Tools in Transforming Patient Care

Improving patient care requires more than good intentions; it demands a disciplined, theory-driven approach that connects innovation to implementation and evidence to action.

Read More Articles

Myosin’s Molecular Toggle: How Dimerization of the Globular Tail Domain Controls the Motor Function of Myo5a

Myo5a exists in either an inhibited, triangulated rest or an extended, motile activation, each conformation dictated by the interplay between the GTD and its surroundings.

Designing Better Sugar Stoppers: Engineering Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors via Fragment-Based Dynamic Chemistry

One of the most pressing challenges in anti-diabetic therapy is reducing the unpleasant and often debilitating gastrointestinal side effects that accompany α-amylase inhibition.