While significant progression has been made in cancer therapeutics, the disease remains a serious health risk. The lack of commercially available diagnostic biomarkers hinders accurate early cancer diagnosis which could otherwise save many lives. Protein-based biomarkers have demonstrated the potential to introduce non-invasive diagnostics for cancer patients.

Biomarkers are an important tool in precision medicine across a number of therapeutic areas. In oncology, genetic profiling technology and targeted cell therapies have seen biomarkers play an important role in disease management for cancer patients.

A cancer biomarker refers to a “tumor characteristic or a response of the body in the presence of cancer that can be objectively measured and evaluated”. Circulating tumour markers found in bodily fluids like blood and urine are currently implemented in clinical investigations. These biomarkers are often used to measure the risk of developing the disease, response to therapy, and estimate prognosis.

The prominent issue however is that “although an elevated level of a circulating tumor marker may suggest the presence of cancer… this alone is not enough to diagnose cancer”. This represents an unmet clinical need to identify and validate a diagnostic biomarker that can be used alone (i.e. not in conjunction with other methods) to diagnose cancer types.

Cancer diagnostics based on protein biomarker detection have shown obvious potential for a number of years. For example, serum protein expression is often significantly raised in patients’ samples which are affected by colon and other cancers.

In the last decade, protein-based diagnostic biomarkers are receiving increasing clinical attention due to their implication in cancer pathology and potential for non-invasive detection.

Protein-based diagnostic biomarkers

In order to utilise protein-based biomarkers, there must be significant proteomic changes that occur specific to cancer. Mutations in cancer-associated genes, for example, can be manifested in defective protein structure. These defects can impact protein stability and cause the protein to become more susceptible for degradation.

Proteomic studies into colon cancer have identified a number of protein biomarkers for potential diagnostic and therapeutic applications. “The over-expressed glycoprotein is responsible for tumor growth and spread into distinct parts.” The secreted protein has also been associated with a number of malignancies including the stomach, prostate and liver.

As of today, there are no protein-based biomarkers that have surpassed clinical studies for application in clinical practice. However, in the last decade, researchers have been focused on continuing to develop assays to more accurately detect potential biomarker candidates in comparison to traditional techniques.

One example is the proximity extension assay (PEA) which was used in a 2019 study identifying plasma protein biomarker signatures for ovarian cancer.

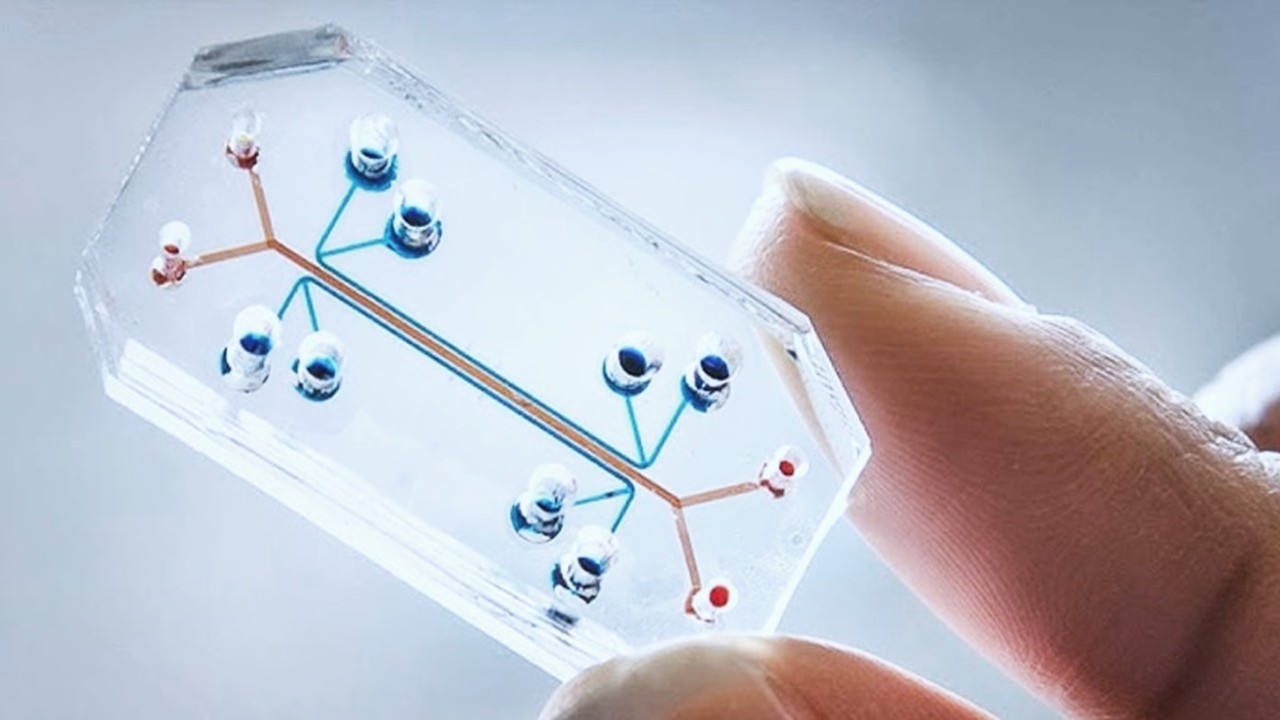

PEA technology is high-throughput fluid protein biomarker detection immunoassay. The system is based upon a “unique antibody-oligonucleotide protein binding for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based measurement”. The amplification by PCR and hybridisation of a labelled probe to its DNA target generates a highly sensitive detection of proteins, protein modifications or protein-protein interactions.

Hybridisation, in the context of assays, involves the labelling of nucleic acid which aims to identify related DNA/RNA within a complex mixture of unlabelled nucleic acids.

In this aforementioned 2019 study, it was emphasised that a non-invasive diagnostic test with higher sensitivity and greater specificity could be used to distinguish between women with malignant and benign masses. The benefit of this could prevent over-diagnostic surgery which can be unnecessary and introduce health complications.

A 2020 study chose to use mass spectrometry-based high throughput screening in order to identify protein biomarker candidates detected in the human blood. The aim of the study was to develop a panel of proteins which can distinguish patients with lung cancer from health donors via plasma samples.

The results from the assay identified six blood-based proteins which could be used as a potential diagnostic tool in lung cancer. This is an important step forward in identifying biomarker candidates which could be validated and potentially be used for clinical practice. Furthermore, “the 6-protein panel non-invasively detected lung cancer at different stages of the disease (including stage I), suggesting its high potential as a screening tool”.

Challenges

The analytical challenges of screening the vast number of proteins is one of the major stumbling blocks for protein-based biomarker screening. Heterogeneity refers to the level of diversity within individuals. In the context of proteomics, it refers to the magnitude of proteomic variations between normal individuals and different disease states.

The implication of heterogeneity makes it difficult to standardise protein-based biomarkers for an entire patient population due to proteomic diversity.

A recent approach in the last few years has been developed to try and circumvent the challenge of tumor heterogeneity. The combination of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation with imaging mass spectroscopy allows “proteomics-based studies to provide both patient-specific and cancer-specific information as a means for biomarker discovery and cancer tissue classification. It also provides morphology-based proteomics analysis for cancer tissue”.

Unfortunately, several technical challenges still exist including low signal-to-noise ratio and low mass accuracy.

Validation of cancer biomarkers has proven to be a challenge that has hindered progress in reaching the clinic. To meet statistical requirements for a potential protein biomarker, patient samples will be required to expand further accompanied by excellent clinical data. This is not always feasible as patients are not always comfortable with samples being used in clinical studies nor do they appreciate the biopsy procedure.

One suggested solution to find and validate new biomarkers is to develop biobanks with numerous consecutive samples collected over time from each of large numbers of individuals. A biobank is a “collection of human biological samples and associated information organized in a systematic way for research purposes”.

In addition to supporting validation, biobanks could also help define the normal protein biomarker concentration ranges. These ranges frequently differ across the population due to genetic and environmental factors, which could provide more information about the level of proteomic diversity with regards to specific cancer types.

While research needs to overcome the challenges of biomarker validation and heterogeneity, protein-based diagnostic biomarkers show promise. The development of accurate, non-invasive diagnostic tools would allow patients to receive rapid and accurate diagnosis to support clinical decisions for personalised therapies. Furthermore, it could prevent patients receiving unnecessary surgery which could impact their mental and physical health.

Charlotte Di Salvo, Lead Medical Writer

PharmaFeatures

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Immunology & Oncology

The Silent Guardian: How GAS1 Shapes the Landscape of Metastatic Melanoma

GAS1’s discovery represents a beacon of hope in the fight against metastatic disease.

Immunology & Oncology

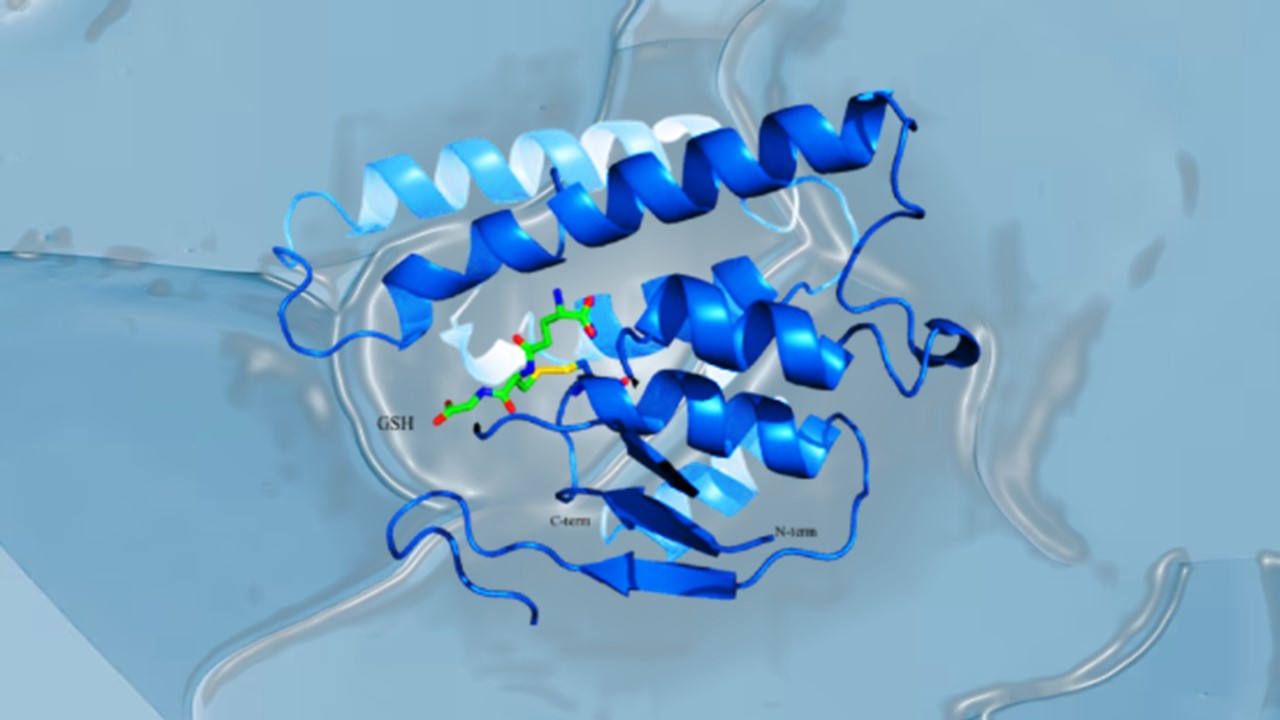

Resistance Mechanisms Unveiled: The Role of Glutathione S-Transferase in Cancer Therapy Failures

Understanding this dual role of GSTs as both protectors and accomplices to malignancies is central to tackling drug resistance.

Read More Articles

Myosin’s Molecular Toggle: How Dimerization of the Globular Tail Domain Controls the Motor Function of Myo5a

Myo5a exists in either an inhibited, triangulated rest or an extended, motile activation, each conformation dictated by the interplay between the GTD and its surroundings.

Designing Better Sugar Stoppers: Engineering Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors via Fragment-Based Dynamic Chemistry

One of the most pressing challenges in anti-diabetic therapy is reducing the unpleasant and often debilitating gastrointestinal side effects that accompany α-amylase inhibition.