RNA has proven in the last decade to be a valid therapeutic target for a multitude of diseases. The ability to manipulate the genetic code to produce almost any protein is one of the many advantages that has also led to the development of RNA-based vaccines. We look at many positive outcomes continued research into this molecule can bring, including successful mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and a new class of drug targets for triple-negative breast cancer.

Introduction to RNA

RNA is a molecule made up of small building blocks called nucleotides. RNA is primarily single-stranded, however special RNA viruses exist as double-stranded. RNA is synthesised from DNA by an enzyme known as RNA polymerase in a process called transcription. The primary function of RNA is protein synthesis which occurs in a process called translation. Other critical functions include the modification of other RNAs and regulation of gene expression during growth and development. The three main forms of RNA involved in protein synthesis are mRNA (messenger RNA), rRNA, and tRNA.

In terms of their association with disease, genetic mutations that occur in RNA are a problem. Errors in the sequence of nucleotides can result in defects in the RNA complex impacting the cellular processes that RNA maintains. As a result, disruption to cellular processes can lead to disease development.

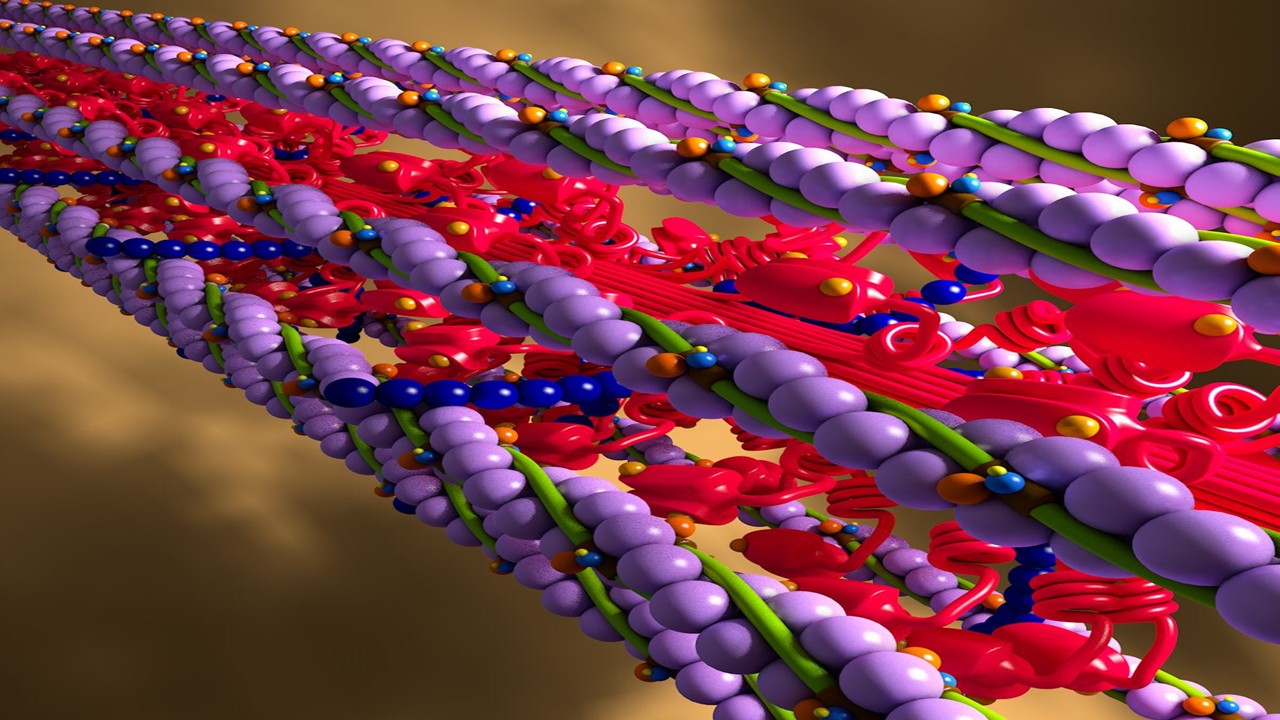

A 2018 review highlighted the specific mutations in the gene coding for RNA exosome subunits that cause human disease. The RNA exosome is a multi-unit protein complex that catalyses the processing or degradation of many types of RNA. According to another review of RNA, mutations in the exosome subunit genes EXOSC3 and EXOSC8 have been associated with pontocerebellar hypoplasia, a group of rare conditions characterised by an abnormal prenatal development of the cerebellum and brainstem. The abnormally small cerebellum and brain stem result in defined psychomotor retardation. Manifestations of psychomotor retardation include “slowed speech, decreased movement, and impaired cognitive function”.

Principles for targeting RNA with drug-like small molecules

With diseases like pontocerebellar hypoplasia which support the implication of RNA mutation, it opens the door for targeting RNA with drug-like small molecules. The great diversity in the structure and function of RNAs increases the number of options for druggable targets.

Several studies establish that RNA is a valid target of small molecules, and that ligands can bind to isolated binding pockets in RNA. One such discovery was “the development of small molecule screens against functionally defined viral RNA motifs, such as human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1)”.

There are three main components necessary to enable optimal RNA-targeted drug discovery as highlighted in a Nature article: (1) valid therapeutic RNA target, (2) suitable screening approach to identify ‘drug-like lead molecules’ with the desired pharmacological properties, and (3) establishing RNA motifs with high specificity and potency binding to a high quality pocket. It was also emphasised that ensuring the ligand-binding properties of the RNA target was equally as important as the validated target RNA itself.

Why are pharmaceutical companies so eager to exploit RNA for therapeutic purposes?

Previously RNA therapeutic research was conducted in academia by labs who employed scientists with expertise in cellular biology and assay development. In the last few years however, the increasing collaboration between pharma and academia has seen many pharmaceutical companies expand their pipelines in RNA research.

There are a number of reasons as to why pharma companies and biotechs are drawn to developing RNA therapeutics. Advantages of RNA-based drugs that are driving development include:

(1) Their ability to act on targets that are otherwise “undruggable” for a small molecule or a protein

(2) Their rapid and cost-effective development, in comparison to small molecules or recombinant proteins

(3) The ability to rapidly alter the sequence of the mRNA construct for personalised treatments or to adapt to an evolving pathogen.

Continuous advancements in stability, chemical modification and delivery systems will no doubt continue to see increased commercialisation of RNA therapeutics. In the last few years, the industry has seen a number of significant collaborations and partnerships to further RNA research and development. Independent pharma group Servier recently entered a strategic collaboration with Nymirum, described as a “pioneer in RNA-targeted small molecules”.

According to a recent news article, the collaboration hopes to “identify and develop RNA-modulatory drugs for the treatment of neurological diseases”. Neurodegenerative disorders especially are difficult to treat with small molecules due to complex pathology, and the potential to target undruggable makes RNA-based therapeutics a desirable approach.

Therapeutic applications

RNA-based vaccines

Vaccines take advantage of the highly-evolved human immune system, and essentially trick it into thinking it has become infected in order to promote the production of antibodies by B cells.

Live attenuated, inactivated pathogens and subunit vaccines are conventional vaccines which have proven successful against many diseases including polio and smallpox. However there have been flaws, with some able to evade the adaptive immune response.

mRNA vaccines are a promising alternative to conventional approaches to vaccination. These vaccines initiate an immune response by introducing mRNA into the cells which have been engineered to carry the genetic instructions to produce the pathogen antigen. Through protein synthesis, the antigens are created which stimulate an immune response in the host and antigen copies are stored by memory cells for future immunity.

The many advantages to using RNA-based vaccines have been acknowledged for a number of years and are highlighted in a 2018 Nature article:

• mRNA-based vaccines are non-infectious

• mRNA is degraded by normal cellular processes, so there is no naked genetic code remaining in the host’s cells

• mRNAs possess an ‘inherent immunogenicity’. Immunogenicity refers to the ability of a foreign substance to induce an immune response. This “can be down-modulated to further increase the safety profile”.

• Production of mRNA vaccines shows potential for rapid, inexpensive, and scalable manufacturing

Potential new class of drug target for breast cancer: RNA-binding protein

RNA-binding proteins have been under the spotlight over the last couple years as a potential therapeutic target for breast cancer. A study recently published in July this year discovered a number of RNA-binding proteins within human cells and mouse models of cancer, specifically YTHDF2.

Mice models were developed from the transplant of human cells from triple-negative breast tumours into the rodent. It was found that with the removal of YTHDF2 from the tumours shrank “approximately 10-fold in volume”.

This represents an exciting era for cancer treatment, with the potential to develop precision medicine that is more effective, with fewer side effects and offers hope for patient populations with treatment resistance and rare cancer types.

Charlotte Di Salvo, Former Editor & Chief Medical Writer

PharmaFEATURES

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Molecular Biology & Biotechnology

Myosin’s Molecular Toggle: How Dimerization of the Globular Tail Domain Controls the Motor Function of Myo5a

Myo5a exists in either an inhibited, triangulated rest or an extended, motile activation, each conformation dictated by the interplay between the GTD and its surroundings.

Drug Discovery Biology

Unlocking GPCR Mysteries: How Surface Plasmon Resonance Fragment Screening Revolutionizes Drug Discovery for Membrane Proteins

Surface plasmon resonance has emerged as a cornerstone of fragment-based drug discovery, particularly for GPCRs.