Off-label drugs have provided a lifeline for patients for whom standard treatment either fails to improve their condition or doesn’t exist. Unfortunately, there remains a level of controversy surrounding off-label information with some for and against its distribution. Understanding the regulatory process for off-label use remains misunderstood and raises concerns including the reliability information like safety and efficacy data.

Introduction

Drug repurposing has continued to become prevalent in the clinical setting, whereby healthcare professionals recommend a drug for a disease other than what it was marketed for. These are known as off-label drugs, in which regulatory bodies such as the FDA do not support the safety or efficacy of a drug for unapproved use. The decision to offer an off-label drug is typically made by the clinician or physician taking care of the patient.

An example of drug repurposing would be rituximab, which is used as an off-label therapy for the treatment of myasthenia gravis, compared to eculizumab, which is approved for this indication.

In addition to off-label drugs being used for unapproved use, off-label use can also refer to a treatment being delivered in a different way. For example, a drug which has been approved as a capsule, may be offered as an oral solution. Another form of off-label use is changing the approved dosing, whether it be increasing or decreasing the daily dose.

There are a number of reasons as to why an off-label drug will be recommended for use. One of the most common reasons is when a patient is refractory to the standard-of-care therapies. In other words, they have demonstrated a poor clinical response to current therapies available.

This is a frequent occurrence for patients with neurological disorders – the vast number and complexity of neural connections in the human brain often means that many neurological diseases share pathological origins from the same region. Hence, treatment for the symptoms of one neurological disorder may be applicable for another. A number of anticonvulsants such as lamotrigine, which is typically prescribed for epilepsy, has been used as off-label drugs to treat symptoms for psychiatric disorders like PTSD and bipolar disorder.

Another reason why a patient may be offered off-label treatment, is that there may not be any available therapies for their condition. This can be the case for a number of patient populations including paediatric patients and those with rare diseases.

The repurposing of ‘on-label’ drugs has been utilised across many therapeutic areas including cardiology and infectious diseases, but is especially popular in the field of oncology. One example is all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA), a vitamin A derivative used to treat acne that was authorised in Europe to treat adult patients with newly diagnosed low-to-intermediate risk acute promyelocytic leukemia in combination with Trisenox.

It is important to clarify the difference between drug repurposing and off-label drugs – in the case of ATRA, the drug received approval for use in cancer patients, though originally used for acne treatment. Off-label drugs are again, drugs used for an alternative purpose, but have not been approved for that use by regulatory bodies.

From a pharmaceutical perspective, utilising off-label therapy can cut R&D time and potentially lower development costs for drugs of new indications rather than de novo medicine.

FDA off-label regulations

Although FDA regulations do not directly prohibit the promotion of off-label uses, it has been observed that two provisions achieve this indirectly:

• Pharmaceutical manufacturers are prohibited from introducing a drug into ‘interstate commerce’ unless the FDA has approved the drug and its label

• A second provision barres manufacturers from introducing misbranded drugs into interstate commerce.

Misbranding can be described as drug labeling that contains information detailing unapproved uses or is insufficient to support safe use for even approved indications. Pharma companies are bound by FDA regulations to submit safety and efficacy data as well as FDA approval, prior to marketing a new drug indication.

While the FDA prohibits the promotion of off-label use by pharma companies, there are many permitted sources which are available for publishing off-label information. Examples include journal articles, medical liaisons, and sales representatives. While medical sales reps may appear biased, they are allowed to “provide copies of peer-reviewed journal articles to health care professionals but are not permitted to use them to promote company products”.

Controversies Regarding the Distribution Of Off-Label Information

There remains a controversy around the distribution of off-label information which varies across the pharmaceutical industry and clinical setting. A number of arguments have been made for the distribution of off-label information:

One of the main advantages is that physicians can easily access available data in order to make more informed treatment decisions. This is particularly useful, as it can be difficult for physicians to independently keep current with the latest information, hence readily available off-label data can summarise this sufficiently.

Another important argument made is that “because the FDA approval process is so complex, costly, and time-consuming, the distribution of off-label drug information provides physicians and patients with early notification about novel treatments”.

In terms of those against off-label information distribution, one of the concerns is that physicians may not have the time to carefully dissect the information and may solely rely on industry-distributed journal articles. This can be a particular issue for a number of reasons including:

• Quashing data on safety risks

• Ghostwriting of journal articles sponsored by companies

• Misleading portrayal and interpretations of data in low-quality studies

All of these possibilities can have a detrimental effect on patients in terms of their safety, with potential risks of toxicity/side effects, as well as misleading the therapeutic efficacy.

In addition, many insurers and government plans do not cover the cost of off-label medications, describing the treatment as experimental, despite evidence supporting the efficacy. As a result, a problem with physicians utilising this off-label information, is that it can be difficult to support reimbursement.

Hence, the prescribing of off-label treatment to patients can be a costly endeavor which can put a significant strain on their daily life, as well as potential mental distress if they cannot afford it.

It could be suggested that one of the main reasons for arguments against off-label distribution is that the information is not well regulated i.e. stringent regulatory guidelines to prevent misbranding and misleading information that could impact patients. This is something acknowledged by the FDA as described in a recent article, stating that “it is difficult, if not impossible, for the monitoring and surveillance efforts it conducts to identify all off-label promotion that takes place”.

A number of alternative approaches have been emerging to better regulate off-label promotion including industry self-regulation and the requirement for clinical trials to be run for off-label uses. The hope is that off-label information and treatment will become better regulated in order to support their use for patients who will benefit and need it the most.

Charlotte Di Salvo, Lead Medical Writer

PharmaFeatures

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

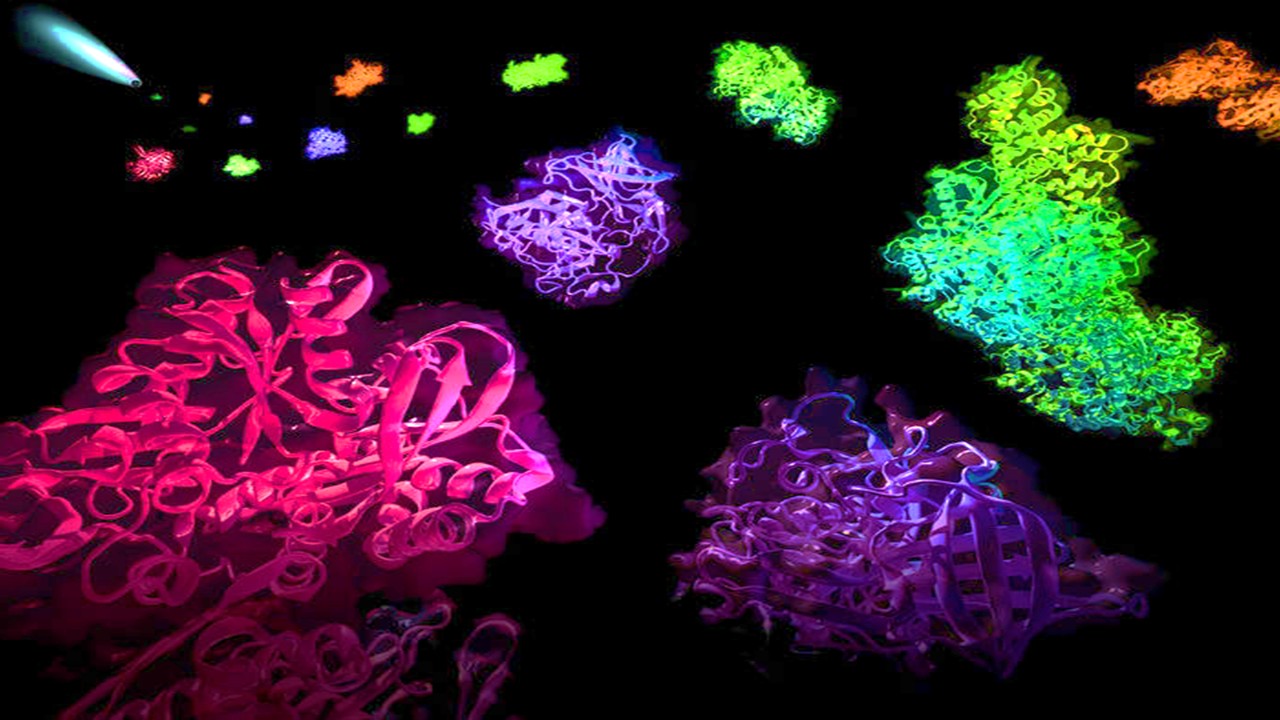

Molecular Biology & Biotechnology

Myosin’s Molecular Toggle: How Dimerization of the Globular Tail Domain Controls the Motor Function of Myo5a

Myo5a exists in either an inhibited, triangulated rest or an extended, motile activation, each conformation dictated by the interplay between the GTD and its surroundings.

Drug Discovery Biology

Unlocking GPCR Mysteries: How Surface Plasmon Resonance Fragment Screening Revolutionizes Drug Discovery for Membrane Proteins

Surface plasmon resonance has emerged as a cornerstone of fragment-based drug discovery, particularly for GPCRs.

Read More Articles

Designing Better Sugar Stoppers: Engineering Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors via Fragment-Based Dynamic Chemistry

One of the most pressing challenges in anti-diabetic therapy is reducing the unpleasant and often debilitating gastrointestinal side effects that accompany α-amylase inhibition.