For years, scientists have been searching for ways to cure HIV, a virus that affects millions of people globally. Despite advances in antiretroviral therapy, which can suppress the virus to nearly undetectable levels, complete eradication of the virus has yet to be achieved. A recent study published in Nature Microbiology suggests that monocytes, a type of circulating white blood cell, could be another stable reservoir for HIV genomes.

What are Monocytes and Macrophages?

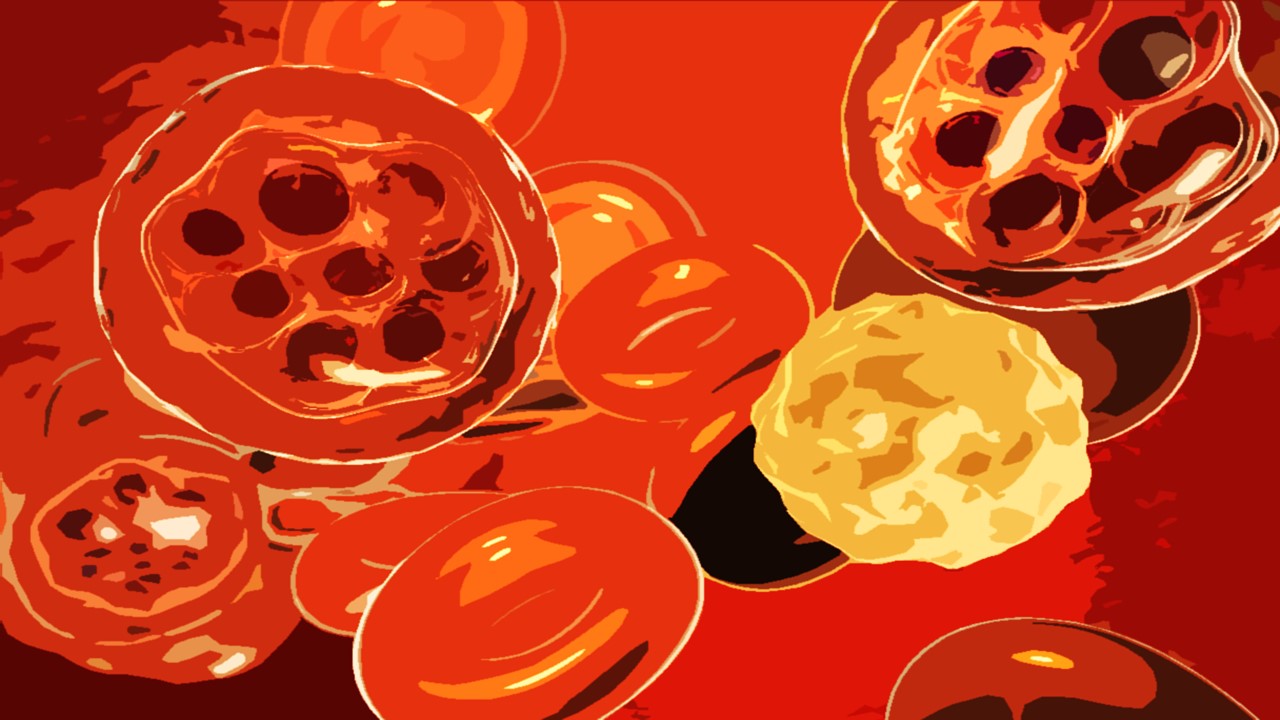

Monocytes are a type of white blood cell, specifically a type of leukocyte, that play a key role in the immune system. They are produced in the bone marrow and circulate in the bloodstream, where they help to identify and destroy pathogens and foreign particles. Monocytes are also involved in the process of inflammation and tissue repair. In addition, they can differentiate into specialized cells called macrophages or dendritic cells, which have distinct functions in the immune system.

Macrophages are large phagocytic cells that engulf and digest invading microorganisms, foreign particles, and dead cells. They play a key role in innate immunity and inflammation, and are also involved in tissue repair and remodeling. Macrophages are found in various tissues throughout the body, such as the liver, spleen, lungs, and brain.

In brief, monocytes are short-lived circulating immune cells that differentiate into macrophages, which are immune cells that engulf and destroy viruses, bacteria, and other foreign cells. Macrophages are crucial in fighting off HIV infection, as they can ingest and break down virus particles.

The Study

The study was conducted by a team of scientists led by Johns Hopkins Medicine, who analyzed blood samples from people with HIV on long-term suppressive therapy. The researchers found that monocytes contained stable HIV DNA capable of infecting neighboring cells. Although the levels of HIV DNA in monocytes were 10 times lower than those in CD4+ T cells, the well-established HIV reservoir, the results suggest that monocytes could still be a stable reservoir of HIV.

The Findings

Using an experimental assay, the researchers were able to detect intact HIV genomes in monocytes prior to macrophage differentiation. Furthermore, the virus extracted from infected monocytes was able to infect CD4+ T cells, indicating that HIV can hide in monocytes and produce infectious virus. Three participants had their blood examined several times over the four-year study period, and each time, the scientists found HIV DNA and infectious virus produced by their monocyte-derived macrophages.

Implications for Future Research

The findings of this study open new directions for future research into HIV eradication. The researchers plan to pinpoint the subset of monocytes found to harbor HIV DNA and the source of these infected cells. They hope to gain a better understanding of the role of monocytes and macrophages in HIV infection and the potential of targeting these cells to eradicate HIV.

With continued research and advances in treatment, a cure for HIV may one day be within reach.

Study Funding

The study was funded by multiple sources, including the National Institutes of Health grants P01AI131306, R01AI127142, R01DA050529, R01MH127981, and R01MH113512-03S1. Additional funding was provided by the Johns Hopkins University National Institute of Mental Health Center for Novel Therapeutics for HIV-associated Cognitive Disorders (P30MH075673) and the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research, which is an NIH-funded program (P30AI094189).

Study DOI: 10.1038/s41564-023-01349-3

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Infectious Diseases & Vaccinology

Harnessing IgA: A Breakthrough in HIV Vaccine Innovation

A vaccine eliciting strong IgA responses could revolutionize HIV prevention by protecting the virus’s primary entry points.

Infectious Diseases & Vaccinology

Prostate Cancer Precision-Targeting: The Promise and Challenges of Vaccine Therapies

The future of prostate cancer vaccines lies in combination therapies that harness the strengths of multiple modalities.