Rewriting the DNA of Public Health Through Clinical Innovation

Public health is no longer a practice confined to the dusty corridors of community clinics or reactive health campaigns. It is now increasingly embedded in the very architecture of clinical care, transforming how health systems perceive risk, manage disease, and deploy innovation at scale. At the heart of this evolution lies a tension between the velocity of scientific discovery and the inertia of health care practice. Innovations that could dramatically alter patient outcomes often remain in limbo—tested, validated, and yet unincorporated into the daily routines of clinical care.

This chronic delay in adoption reflects a deeper issue within the ecosystem: the disconnection between empirical breakthroughs and the systems that govern, fund, and standardize care. What begins in clinical trials too often remains there, isolated from the waiting rooms where it matters most. There is now a growing recognition that transforming individual health care decisions requires not just evidence, but infrastructure—legal, institutional, and operational. Legal mandates, reimbursement strategies, quality metrics, and digital technologies have become the levers that enable population-scale transformation.

Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the field of fall prevention for older adults, a burgeoning crisis largely ignored despite the wealth of evidence-based interventions available. The slow uptake of fall prevention services reveals how deeply structural and policy-driven barriers can suppress even the most compelling scientific advancements. In contrast, successful national-level implementation, as seen in hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening, demonstrates what is possible when innovation is aligned with legal mandates, insurance coverage, and clinical decision support.

As public health converges with clinical quality reform, a new model emerges—one in which legal frameworks act not as afterthoughts to medical progress but as engines that determine whether and how that progress reaches the public.

Legal Catalysts: The Invisible Hand Guiding Medical Standards

Medical practice does not evolve in a vacuum. It is shaped by a confluence of regulatory frameworks, malpractice litigation, and institutional mandates. While individual lawsuits like Helling v Carey have highlighted the legal liability associated with ignoring low-cost, effective screening technologies, they are rare and often yield inconsistent results. Legal action alone cannot provide the consistency or scalability needed for systemic reform, but it can serve as a cautionary tale—an incentive for clinicians and institutions to reevaluate the standards that govern routine care.

More potent than litigation, however, are statutory and regulatory mechanisms that compel the integration of evidence-based practices into health care delivery. In the United States, these mechanisms have evolved significantly in recent years, as public health policymakers recognize the necessity of embedding preventive care within reimbursable service structures. In particular, legislative tools such as the Affordable Care Act have been instrumental in codifying quality improvement strategies—redefining what counts as reimbursable care and aligning incentives with outcomes rather than procedures.

This legal recalibration signals a departure from the historically reactive nature of health care delivery toward a proactive, systematized approach. Innovations that were once siloed in academic journals are increasingly finding their way into standardized care through policy enforcement, certification requirements, and reimbursement protocols. In this paradigm, innovation diffusion is no longer left to organic uptake; it is orchestrated through legal scaffolding.

The system’s responsiveness to legal imperatives is both its strength and its weakness. While regulation can catalyze adoption, its absence can equally serve as a barrier. Falls-risk screening, for instance, remains underutilized in part because it lacks the regulatory weight carried by USPSTF A or B-rated interventions. This absence translates into limited reimbursement, diminished provider motivation, and ultimately, missed opportunities for early intervention.

The Six Pillars of Adoption: Anatomy of a Scalable Innovation

Adoption of clinical innovations does not occur by chance; it hinges on a constellation of characteristics that determine how easily a new intervention fits into the existing health care environment. These six attributes—credibility, relative advantage, simplicity, testability, observability, and compatibility—act as the sinews connecting research to real-world application.

Credibility is the foundational attribute. Without robust evidence, no amount of regulatory backing or financial incentive can legitimize an intervention. Relative advantage speaks to the pragmatic calculus performed by clinicians and administrators: does the innovation outperform current practice in terms of outcomes, cost, or efficiency? If the answer is yes, adoption becomes conceivable. Simplicity, meanwhile, is more than aesthetic—it defines operational feasibility. Complex innovations, regardless of their efficacy, are often abandoned in environments strained by time and resource constraints.

Testability allows for a cautious engagement with new practices. Pilot programs and modular deployment permit institutions to explore utility without full commitment. Observability enhances the contagious nature of innovation. When clinicians witness tangible outcomes—either through patient feedback or internal metrics—the perceived value becomes harder to ignore. Finally, compatibility speaks to the underlying ethos and infrastructure of the institution. If an innovation disrupts existing workflows or defies reimbursement norms, it is likely to face resistance.

In the context of falls prevention, these pillars are inconsistently met. The interventions are credible and clinically validated, but they lack the financial testability and regulatory compatibility found in more widely adopted programs like HCV screening. Without coding infrastructure or bundled payment incentives, falls prevention remains an outlier in a system optimized for billable events.

Institutional Gatekeeping: The Role of Leadership and Infrastructure

Health care organizations are not monolithic; they are ecosystems characterized by inertia, competing priorities, and siloed operational domains. In such an environment, the decision to adopt a new practice rests heavily on leadership’s willingness to invest in long-term change. This investment is not only financial but strategic. Leaders must decide whether an innovation aligns with institutional goals, regulatory requirements, and quality benchmarks.

For an innovation to become routine, it must be championed from both the top and the middle—executive leadership and clinical influencers must act in concert. Clinical champions are especially pivotal; their endorsement translates scientific rationale into operational feasibility. However, even the most enthusiastic champions are hamstrung without supportive infrastructure. Electronic health record systems must be updated, clinical staff must be retrained, and workflows must be redesigned to accommodate new tasks.

These internal adjustments are particularly burdensome for resource-limited settings such as community health centers. In these contexts, the burden of unmet needs, limited staffing, and financial precarity makes innovation adoption a secondary concern. Prevention-oriented innovations like falls-risk screening are particularly vulnerable to de-prioritization because they often require extended patient engagement without immediate payoff.

Nonetheless, when leadership aligns with infrastructure and financial incentive, innovation can be rapidly absorbed. The hepatitis C example illustrates this alignment in action: a validated intervention, bolstered by insurance mandates, quality reporting, and clinical decision support tools, created a self-reinforcing feedback loop that normalized HCV screening in clinical workflows.

Passive Dissemination Versus Strategic Scaling

Simply publishing evidence or issuing clinical guidelines does not guarantee behavior change. Knowledge alone does not translate into adoption. Passive dissemination methods—scientific publications, continuing medical education, or clinical symposia—have proven largely ineffective in altering clinical practice. They elevate awareness but fall short in motivating operational transformation.

Strategic scaling requires a coordinated suite of mechanisms that reinforce adoption at every stage of the health care continuum. These include regulatory mandates, financial incentives, technological enablers, and workforce alignment. The shift from knowledge diffusion to behavioral change is made possible when interventions are not only visible and validated but also economically and operationally irresistible.

Payment structures that reward quality rather than volume, benefit designs that reduce patient cost-sharing, and surveillance tools that monitor performance all contribute to this ecosystem. Without these scaffolds, even the most promising innovations remain aspirational rather than actionable.

The consequence of relying on passive diffusion is evident in the case of fall prevention. Despite strong clinical backing and demonstrated outcomes, uptake remains abysmal due to the absence of reinforcing policies, reimbursement mechanisms, and workflow integration. This inertia not only stymies public health gains but also perpetuates disparities in access to preventive care.

Leveraging Structural Tools: From Reimbursement to Decision Support

A suite of structural tools has emerged to facilitate the institutionalization of innovation. These include benefit design laws, payment reforms, quality reporting metrics, disease registries, and clinical decision support systems. Each tool addresses a different layer of the health care matrix, collectively forming a framework for systemic adoption.

Benefit design mandates ensure that insurance coverage aligns with clinical innovation. By requiring coverage of specific interventions, they eliminate financial barriers for patients and institutional hesitancy due to reimbursement uncertainties. Payment reforms such as bundled payments and value-based care models further reinforce this alignment by tying reimbursement to outcomes rather than services rendered.

Quality reporting transforms compliance into a measurable asset. Through systems like the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), providers are rewarded for adherence to evidence-based practices, making innovation a performance metric rather than a discretionary choice. Meanwhile, disease registries offer real-time surveillance data, enabling institutions to identify gaps in care and benchmark performance.

Clinical decision support systems, perhaps the most agile of these tools, operate at the point of care. Embedded within electronic health records, they guide clinicians toward best practices by integrating patient-specific data with clinical guidelines. These tools not only enhance decision-making but normalize innovation within daily workflows, particularly when configured to issue real-time prompts or reminders.

Hepatitis C: A Blueprint for Coordinated Diffusion

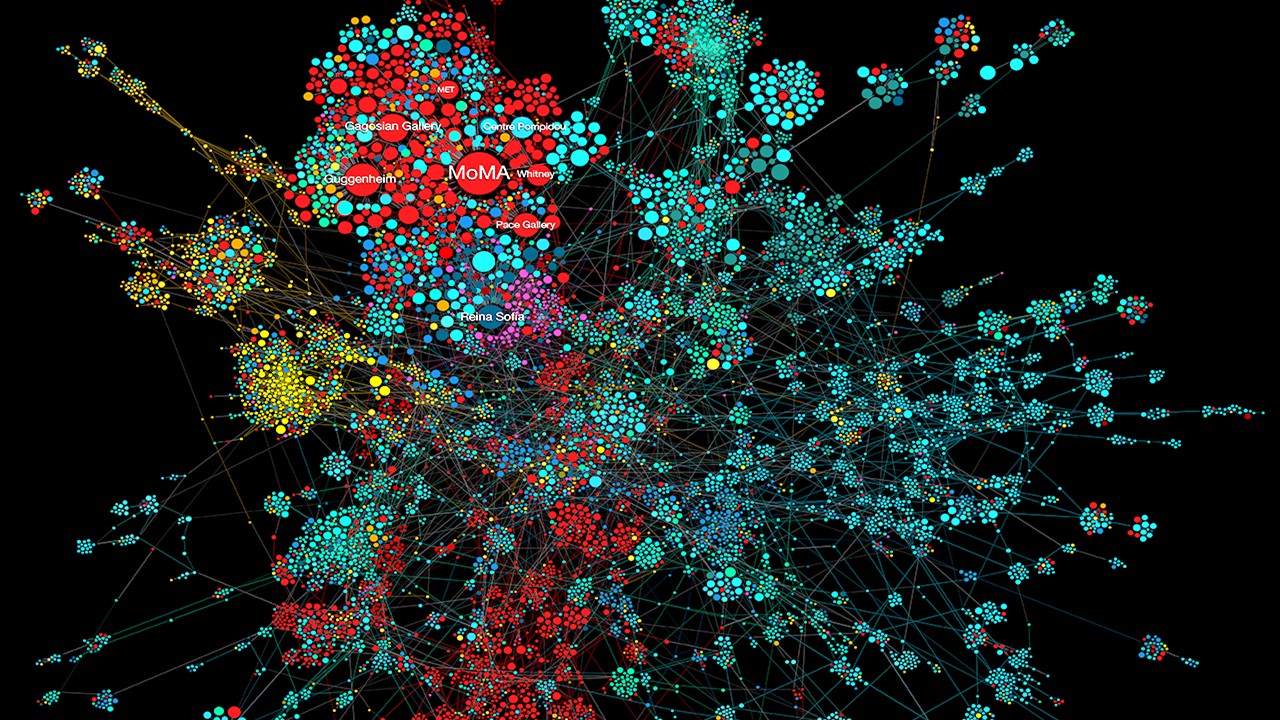

The systemic response to hepatitis C illustrates what is possible when innovation is scaled through strategic alignment. Beginning with a strong evidence base and a USPSTF recommendation, HCV screening was rapidly integrated into the health care infrastructure through multiple channels. Insurance mandates eliminated cost barriers, Medicare incorporated it into quality reporting systems, and clinical decision tools facilitated provider adherence.

The result was a dramatic increase in screening uptake, particularly among patients born between 1945 and 1965. The alignment of legal, technological, and clinical tools created an environment in which screening became not only possible but inevitable. Even within individual practices, the impact was measurable. Clinics that embedded electronic reminders into their health records saw exponential increases in screening rates compared to those that relied on provider discretion.

This example highlights the multiplicative effect of concurrent scaling tools. It also underscores the role of public health policy in orchestrating adoption. The lesson is clear: innovation cannot be left to chance. It must be cultivated through deliberate, multi-tiered strategies that address not just clinical feasibility, but legal, financial, and operational compatibility.

The Case of Falls: An Innovation Without Infrastructure

In stark contrast to the hepatitis C story is the ongoing struggle to implement falls prevention programs. Despite the availability of evidence-based interventions—ranging from medication reviews to vitamin D supplementation—adoption remains dismal. The absence of USPSTF recommendations, lack of unique procedural codes, and insufficient reimbursement mechanisms collectively stall the diffusion process.

Clinicians face numerous barriers: time constraints, limited reimbursement, workflow incompatibility, and competing priorities during wellness visits. Without systemic incentives, preventive conversations about fall risk are often omitted, even when risk is high. The consequence is a missed opportunity to intervene before injury, hospitalization, or long-term disability occurs.

Attempts are under way to rectify this imbalance. USPSTF reviews are in progress, and new quality measures are being designed. Yet, until the structural supports are in place—particularly those related to reimbursement and quality metrics—falls prevention will remain an orphaned innovation. Lessons from the HCV model suggest that success will require coordinated engagement across legal, technological, and institutional domains.

Toward a New Public Health Strategy: Coordinated, Codified, Scalable

Clinical innovation is no longer merely a matter of scientific advancement. It is a function of systems design. As public health increasingly intersects with clinical care, the ability to scale proven interventions becomes a core competency. This requires a departure from fragmented, reactive strategies toward an integrated model in which legal mandates, economic incentives, and operational tools converge.

Scaling tools should not be viewed in isolation. Their true power lies in synergy. Payment reform, benefit design, surveillance infrastructure, and decision support systems—when aligned—can reshape the landscape of preventive care. They do not just facilitate adoption; they redefine it as an institutional default.

In this context, the role of policy becomes clear: to transform potential into practice, to ensure that the tools of innovation are not merely available but inescapable. In doing so, public health can finally fulfill its mandate—not just to respond to illness, but to preempt it.

Study DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354917709982

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Clinical Operations

Beyond the Intervention: Deconstructing the Science of Healthcare Improvement

Improvement science is not a discipline in search of purity. It is a field forged in the crucible of complexity.

Clinical Operations

Cracking the Code of Clinical Change: Theories as Tools in Transforming Patient Care

Improving patient care requires more than good intentions; it demands a disciplined, theory-driven approach that connects innovation to implementation and evidence to action.

Read More Articles

Myosin’s Molecular Toggle: How Dimerization of the Globular Tail Domain Controls the Motor Function of Myo5a

Myo5a exists in either an inhibited, triangulated rest or an extended, motile activation, each conformation dictated by the interplay between the GTD and its surroundings.

Designing Better Sugar Stoppers: Engineering Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors via Fragment-Based Dynamic Chemistry

One of the most pressing challenges in anti-diabetic therapy is reducing the unpleasant and often debilitating gastrointestinal side effects that accompany α-amylase inhibition.