Fragment-Based Drug Discovery: A Paradigm Shift

The emergence of fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) has redefined the pursuit of novel therapeutics by leveraging low molecular weight compounds to explore vast chemical spaces. Unlike traditional high-throughput screening (HTS), which relies on large libraries of drug-sized molecules, FBDD employs fragments—small molecules with 8–23 non-hydrogen atoms—to maximize chemical diversity while minimizing structural complexity. These fragments, though weak in binding affinity, serve as efficient starting points for optimization into high-affinity ligands through systematic structural elaboration. The foundational principles of FBDD rest on three pillars: the expansive coverage of chemical space by fragments, the reduced risk of unfavorable interactions due to their simplicity, and the feasibility of affinity enhancement via structure-guided design. This approach contrasts sharply with HTS, where the sheer size of compound libraries often obscures meaningful hits, and the emphasis shifts from quantity to quality.

Biophysical validation is indispensable in FBDD, as fragments’ low affinities necessitate highly sensitive techniques to distinguish genuine interactions from false positives. Technologies like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), X-ray crystallography, and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) have historically dominated this space, but surface plasmon resonance (SPR) has risen as a versatile alternative. The ability of SPR to measure real-time binding kinetics and thermodynamics without labels aligns perfectly with FBDD’s demand for precision. Moreover, fragment libraries, typically comprising 500–2000 compounds, align with SPR’s throughput capabilities, enabling rapid screening cycles. This synergy between FBDD and biophysical methods underscores a broader shift toward rational, structure-informed drug design.

The optimization journey from fragment to drug candidate exemplifies the delicate balance between molecular complexity and binding efficiency. Fragments often bind with millimolar to micromolar affinities, necessitating strategic addition of functional groups to enhance potency without compromising ligand efficiency—a metric quantifying binding energy per atom. Structural insights from X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy are critical here, guiding chemists to regions of the target protein where chemical modifications yield maximal affinity gains. This iterative process, though resource-intensive, has produced clinical candidates with remarkable specificity, demonstrating FBDD’s potential to address targets deemed intractable by conventional methods.

Membrane proteins, particularly G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), have long posed challenges for structural and biophysical studies due to their instability in solution. FBDD’s minimal protein consumption and reliance on weak interactions make it uniquely suited for these targets. SPR’s compatibility with membrane proteins, achieved through advanced immobilization strategies, has further cemented its role in GPCR drug discovery. By circumventing the need for crystallization, SPR enables direct observation of fragment binding to GPCRs in near-native states, bridging the gap between biochemical assays and cellular pharmacology.

The convergence of FBDD and SPR represents a broader trend toward integrating biophysical techniques early in drug discovery pipelines. This paradigm not only accelerates hit identification but also enriches the understanding of molecular interactions, paving the way for allosteric modulators and biased agonists. As the pharmaceutical industry grapples with increasingly complex targets, the marriage of fragment-based approaches and label-free biosensors offers a path to innovation, particularly for GPCRs—a family central to human physiology and disease.

The Biophysical Power of Surface Plasmon Resonance

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) operates on the principle of measuring refractive index changes at a sensor surface, enabling real-time, label-free detection of molecular interactions. When a ligand binds to an immobilized target protein, the resulting mass shift alters the plasmon resonance angle, which is quantified as a response signal. This optical phenomenon eliminates the need for fluorescent or radioactive labels, preserving the native binding kinetics and thermodynamics of the interaction. SPR’s ability to simultaneously determine association rates (kₐ), dissociation rates (kd), and equilibrium dissociation constants (K_D) distinguishes it from endpoint assays, providing a dynamic view of molecular engagement. Such kinetic profiling is invaluable for prioritizing fragments with slow off-rates, a trait often correlated with prolonged target occupancy and clinical efficacy.

The versatility of SPR extends beyond mere binding confirmation; it offers insights into stoichiometry and thermodynamic parameters through van’t Hoff analysis. By measuring K_D across temperatures, researchers can derive enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) changes, elucidating the driving forces behind fragment binding. This thermodynamic profiling, while underutilized in current workflows, holds promise for identifying enthalpically driven interactions, which are considered advantageous for optimization. The correlation between SPR-derived thermodynamic data and ITC measurements further validates its robustness, despite requiring orders of magnitude less protein. Such efficiency is critical for membrane proteins like GPCRs, where protein yield remains a bottleneck.

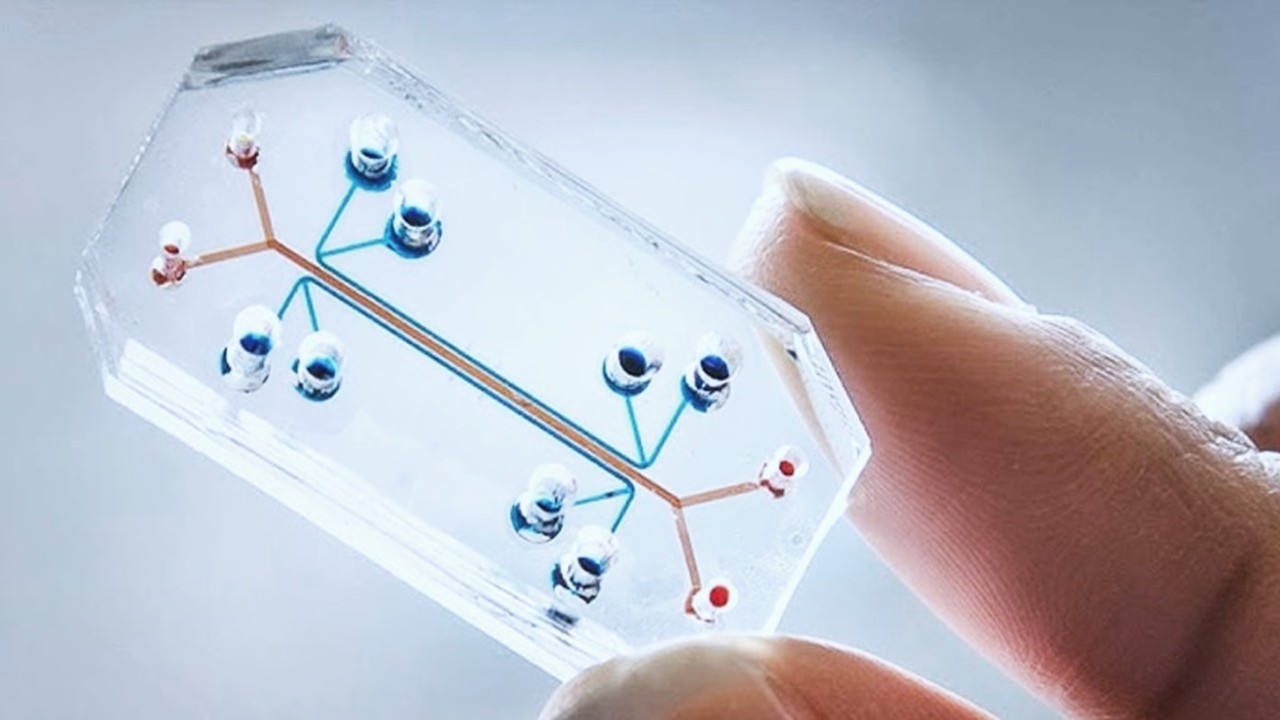

SPR’s experimental flexibility is exemplified by its diverse immobilization strategies, ranging from covalent coupling to affinity-based capture. For GPCRs, immobilization often involves affinity tags such as polyhistidine (His-tag) or antibody-antigen pairs, enabling direct capture from crude lysates. This approach minimizes purification steps, preserving the receptor’s functional conformation and reducing experimental artifacts. The development of stabilized GPCRs (StaRs) with enhanced thermostability has further streamlined SPR workflows, allowing prolonged screening campaigns without protein degradation. These advancements underscore SPR’s adaptability to challenging targets.

Instrumentation advancements, such as the GE Biacore T200 and Sierra Sensors MASS-1, have pushed SPR’s sensitivity to detect fragments as small as 50 Da. Modern systems achieve signal-to-noise ratios capable of discerning sub-1 RU (response unit) shifts, critical for identifying weak binders. High-throughput configurations, including multi-channel flow cells and automated liquid handling, now enable screening of 500–2000 fragments in days, rivaling traditional HTS timelines. This throughput, combined with low protein consumption (25–100 µg per campaign), positions SPR as a frontline tool for FBDD.

Despite its strengths, SPR is not without challenges. Nonspecific binding, solvent effects from dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), and mass transport limitations necessitate meticulous assay design. Referencing strategies—such as parallel immobilization of target and control proteins—mitigate false positives, while dose-response experiments distinguish specific binders from aggregates. The integration of orthogonal assays, like radioligand displacement or functional cellular readouts, remains essential for validating SPR hits, ensuring pharmacological relevance. As these technical hurdles are systematically addressed, SPR’s role in fragment screening continues to expand, particularly for membrane protein targets.

SPR in Fragment Screening: Precision Meets Efficiency

SPR’s ascendancy in fragment screening stems from its dual role as a primary screening tool and a hit-validation platform, consolidating multiple workflow stages into a single methodology. Traditional fragment screens relied on biochemical assays prone to false positives at high compound concentrations, necessitating downstream biophysical confirmation. SPR circumvents this by directly measuring binding events, eliminating the need for secondary assays and accelerating decision-making. Its capacity to operate at low fragment concentrations (≤150 µM) reduces aggregation artifacts, a common pitfall in high-concentration screens. This precision is particularly advantageous for GPCRs, where nonspecific binding complicates conventional approaches.

The efficiency of SPR-based screens is amplified by their minimal protein requirements, a boon for targets like GPCRs that are difficult to express and purify. Unlike NMR or X-ray crystallography, which demand milligram quantities of protein, SPR campaigns can be executed with microgram-level inputs, enabling studies on receptors previously deemed intractable. This economy of scale facilitates iterative screening—testing multiple constructs or solubilization conditions—to identify optimal assay configurations. For instance, detergent screens using SPR can rapidly pinpoint conditions that preserve GPCR stability and ligand-binding competence, informing downstream purification strategies.

Kinetic profiling during primary screening enriches the hit selection process by prioritizing fragments with desirable dissociation rates. Slow off-rates, indicative of prolonged target engagement, are often predictive of in vivo efficacy, making them valuable starting points for optimization. Additionally, SPR’s ability to detect allosteric binders—compounds interacting outside orthosteric sites—broadens the scope of discoverable pharmacophores. This is critical for GPCRs, where allosteric modulators offer subtype selectivity and novel mechanisms of action compared to orthosteric ligands.

The integration of SPR with structure-based drug design (SBDD) creates a virtuous cycle, where fragment-bound structures guide chemical elaboration. For example, SPR-identified hits for the β1-adrenergic receptor were docked into homology models derived from turkey β1AR crystallography, enabling rational scaffold optimization. Subsequent co-crystallization of optimized fragments validated predicted binding modes, demonstrating SPR’s compatibility with iterative SBDD. Such synergy accelerates lead generation, reducing the empirical trial-and-error typical of traditional medicinal chemistry.

Despite these advantages, SPR’s reliance on immobilized proteins introduces potential artifacts, such as conformation-specific trapping or avidity effects. Stabilized GPCRs, locked in agonist or antagonist states, may bias screening outcomes toward certain pharmacologies. Conversely, wild-type receptors captured via affinity tags retain full conformational flexibility but demand rigorous solubilization protocols to maintain activity. Balancing these considerations requires a deep understanding of the target’s biology and the desired therapeutic profile, underscoring the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in FBDD.

Designing Robust SPR Assays for Weak Interactions

Effective SPR assay design hinges on distinguishing specific fragment binding from nonspecific interactions, a task complicated by the weak affinities (µM–mM) inherent to FBDD. Key to this is the implementation of reference surfaces—immobilized control proteins or ligand-blocked targets—to subtract background signals. Multi-channel SPR instruments facilitate simultaneous measurement of test and reference interactions, enhancing data fidelity. For GPCRs, reference surfaces might include inactive mutants, unrelated receptors, or targets saturated with high-affinity ligands, though the latter risks masking allosteric binders.

The concept of R_max—the maximum binding response at saturation—is central to assay sensitivity. Maximizing R_max through high-density protein immobilization improves detection of low-affinity fragments but risks mass transport limitations, where ligand diffusion to the surface becomes rate-limiting. Optimizing flow rates and surface densities mitigates this, ensuring kinetic parameters accurately reflect binding events. Modern instruments like the Biacore T200 achieve sub-1 RU noise levels, enabling reliable detection of fragments with K_D values exceeding screening concentrations—a critical advantage for weak binders.

DMSO, a ubiquitous solvent for fragment libraries, presents a dual challenge: maintaining compound solubility while minimizing refractive index mismatches. Even minor discrepancies in DMSO concentration between samples and running buffer can generate false positives, necessitating precise formulation. “Clean screens” pre-testing fragments for solvent effects or aggregation tendencies reduce noise, enhancing hit confidence. Additionally, dose-response experiments across multiple concentrations help identify nonstoichiometric binders, flagging aggregates or promiscuous compounds for exclusion.

Thermodynamic profiling via van’t Hoff analysis, though underutilized, offers a deeper mechanistic understanding of fragment binding. By correlating temperature-dependent K_D values with enthalpy and entropy changes, researchers can prioritize fragments with enthalpically driven interactions, which are often more amenable to optimization. This approach, validated against ITC data, requires minimal additional protein, making it feasible for GPCRs. However, temperature stability of membrane proteins during prolonged experiments remains a technical hurdle.

The future of SPR assay design lies in automation and data analytics. Machine learning algorithms can parse complex sensorgrams, identifying subtle binding signatures missed by manual analysis. Automated liquid handlers and multiplexed sensors further enhance throughput, enabling large-scale fragment screens against multiple targets in parallel. As these technologies mature, SPR will solidify its position as the gold standard for biophysical screening, particularly for challenging targets like GPCRs.

GPCRs: A Frontier for Fragment-Based Approaches

GPCRs represent one of the most therapeutically relevant protein families, modulating processes from neurotransmission to immune response. Despite their prominence, traditional HTS campaigns have yielded limited success, particularly for peptide-binding receptors and orphan GPCRs. Fragment-based approaches, with their emphasis on ligand efficiency and chemical diversity, offer a promising alternative. SPR’s ability to detect weak, noncompetitive binders is especially valuable here, uncovering allosteric sites and novel chemotypes inaccessible to HTS.

The inherent flexibility of GPCRs—adopting multiple conformations linked to signaling pathways—complicates drug discovery. Biophysical methods like SPR capture these dynamics, revealing ligands that stabilize specific states. For example, SPR screens on β2-adrenergic receptors identified fragments with agonist-like binding profiles, despite their antagonist activity in functional assays. Such discrepancies highlight the nuanced pharmacology accessible through label-free methods, informing the design of biased ligands with tailored signaling outcomes.

Challenges in GPCR fragment screening extend beyond target flexibility to practical issues of protein supply and stability. Wild-type GPCRs, when solubilized in detergents, often lose activity, necessitating stabilization strategies like lipid nanodiscs or thermostabilizing mutations. The latter, exemplified by StaR® technology, locks receptors in defined conformations, simplifying crystallization and screening. However, this stabilization can alter pharmacology, as seen with adenosine A2A StaRs that exhibit reduced agonist affinity. Balancing stability with native function remains a key consideration.

SPR’s compatibility with crude protein extracts streamlines GPCR screening by bypassing lengthy purification. Capturing receptors directly from solubilized membranes onto sensor chips preserves activity and accelerates assay development. For instance, CCR5 receptors captured via C-terminal tags retained ligand-binding competence, enabling SPR screens that identified novel antagonists. This approach, combined with detergent optimization, democratizes GPCR FBDD, extending it to less characterized receptors.

The success of GPCR-FBDD hinges on orthogonal validation. Radioligand displacement assays, functional readouts, and structural studies corroborate SPR hits, ensuring pharmacological relevance. For β1AR fragments, radioligand competition confirmed orthosteric binding, while crystallography validated predicted poses. This multi-modal validation is critical, as SPR alone cannot distinguish orthosteric from allosteric mechanisms. As GPCR structural databases expand, computational docking and molecular dynamics will further augment hit optimization, bridging biophysical data and therapeutic design.

Stabilized Receptors and SPR: Engineering Success

Thermostabilized GPCRs (StaRs) have revolutionized biophysical screening by enabling robust, high-yield production of conformationally homogeneous receptors. Introduced through iterative mutagenesis, StaRs like the adenosine A2A and β1-adrenergic receptors retain ligand-binding competence while resisting denaturation in detergents. SPR screens on these StaRs have identified fragments with nanomolar affinities, underscoring the method’s precision. For example, a 650-fragment screen against β1AR StaR yielded arylpiperazine hits with K_D values of 5.6–16 µM, later optimized into sub-µM leads.

Immobilization strategies for StaRs often leverage histidine tags (His-tag) and nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) sensor chips, enabling reversible capture and surface regeneration. This flexibility facilitates repeated screening cycles, conserving precious protein. The A2A StaR, immobilized via His-tag, demonstrated binding of xanthine derivatives with millimolar affinities—undetectable by traditional assays—highlighting SPR’s sensitivity. Regeneration with weak ligands, like theophylline, further preserved surface activity, a critical factor for large-scale screens.

StaRs’ conformational homogeneity simplifies structural studies, as evidenced by co-crystallization of β1AR fragments. These structures revealed binding poses inaccessible through homology modeling, guiding structure-activity relationship (SAR) campaigns. However, StaRs’ locked conformations limit detection of state-dependent ligands. Antagonist-stabilized StaRs, for instance, may miss agonists or allosteric modulators, necessitating complementary screens on wild-type receptors.

Despite these limitations, StaRs have proven invaluable for probing orthosteric sites. The β1AR StaR screen identified fragments that, when optimized, matched the affinity of clinical β-blockers, validating the approach. Docking these fragments into turkey β1AR structures—despite sequence differences—demonstrated the predictive power of hybrid methods. Such successes underscore StaRs’ role in de-orphaning GPCRs and repurposing existing targets.

The future of StaR technology lies in expanding the repertoire of stabilized conformations. Agonist-stabilized StaRs, though challenging to engineer, could unlock new chemotypes for diseases requiring activation, such as metabolic disorders. Coupled with SPR’s throughput, this expansion promises to illuminate GPCR signaling in unprecedented detail, bridging the gap between structural biology and therapeutic discovery.

Wild-Type GPCRs: Capturing Native Pharmacology with SPR

Screening wild-type GPCRs by SPR preserves native pharmacology, capturing ligands that modulate allosteric sites or stabilize transient conformations. The CCR5 chemokine receptor, immobilized via a C-terminal C9 tag, demonstrated binding of maraviroc—a clinically approved antagonist—with affinities matching cellular assays. This fidelity enabled identification of novel fragments that competed with maraviroc, validating SPR’s relevance to in vivo pharmacology.

Immobilization strategies for wild-type receptors prioritize minimal perturbation. Capturing solubilized receptors from crude lysates via antibody tags (e.g., 1D4 antibody for CCR5) avoids denaturation during purification. Co-immobilization of lipids or cholesterol analogs further stabilizes receptors, mimicking the native membrane environment. Such innovations were pivotal in the β2AR screen, where purified receptors retained agonist and antagonist binding, confirming functional integrity.

Wild-type screens excel in detecting allosteric modulators, as demonstrated by pyrazinyl sulfonamides binding intracellular CCR5 sites. These fragments, undetectable in orthosteric displacement assays, highlight SPR’s capacity to explore noncanonical binding pockets. Reference surfaces blocked with orthosteric ligands help distinguish allosteric binders, though care is needed to avoid discarding novel mechanisms. The β2AR screen, using BI-167107-blocked surfaces, successfully filtered orthosteric hits while preserving allosteric potential.

Challenges persist in achieving sufficient sensitivity for low-molecular-weight fragments. The CCR5 screen, focusing on 260–350 Da compounds, required high receptor density to detect weak binders. Advances in solubilization—such as maltose-neopentyl glycol (MNG) amphiphiles—enhance receptor stability, enabling screens on smaller fragments. The β2AR campaign, testing 94–341 Da compounds, identified hits with nanomolar affinities, proving that wild-type screens can rival StaR-based approaches.

The integration of wild-type SPR data with cellular assays ensures pharmacological relevance. For β2AR fragments, radioligand displacement and functional inhibition confirmed target engagement, while selectivity profiling against β1AR and 27 off-targets validated specificity. This multi-step validation, though resource-intensive, is essential for advancing fragments into leads. As wild-type SPR methodologies mature, they promise to democratize GPCR drug discovery, extending FBDD’s benefits to underexplored receptors.

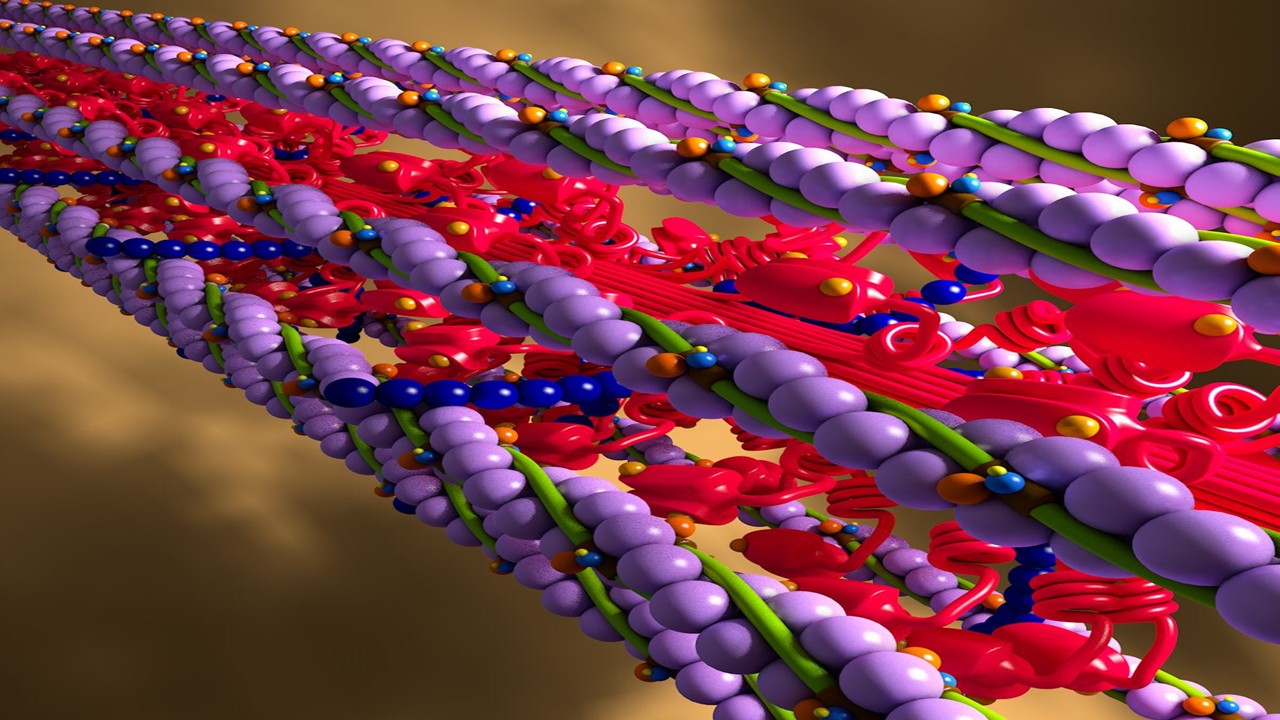

The Perfect Mix for Powerful Computational Biology

Surface plasmon resonance has emerged as a cornerstone of fragment-based drug discovery, particularly for GPCRs—a target class long hindered by technical barriers. By combining label-free kinetics, low protein consumption, and compatibility with membrane proteins, SPR bridges the gap between biophysical screening and cellular pharmacology. Stabilized receptors offer robustness and crystallographic compatibility, while wild-type screens capture native dynamics and allosteric potential.

The integration of SPR with structural biology, computational modeling, and functional assays creates a holistic framework for GPCR drug discovery. As immobilization strategies evolve and instrumentation sensitivity improves, SPR’s application will expand to orphan receptors and complex signaling complexes. The recent successes in identifying high-affinity, selective fragments against β1AR and β2AR herald a new era of rational GPCR targeting, driven by biophysical insights.

Challenges remain—particularly in protein production and assay design—but interdisciplinary collaborations and technological advancements are steadily overcoming these hurdles. As the pharmaceutical industry embraces FBDD for membrane proteins, SPR stands poised to unlock GPCR mysteries, transforming fragment screening from a niche technique into a mainstream pillar of drug discovery.

Study DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2014.09.008

Engr. Dex Marco Tiu Guibelondo, B.Sc. Pharm, R.Ph., B.Sc. CpE

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Molecular Biology & Biotechnology

Myosin’s Molecular Toggle: How Dimerization of the Globular Tail Domain Controls the Motor Function of Myo5a

Myo5a exists in either an inhibited, triangulated rest or an extended, motile activation, each conformation dictated by the interplay between the GTD and its surroundings.

Drug Discovery Biology

Machine Learning Drug Design: Syntactic Mastery in Fragment Linking Through Deep Neural Networks

By treating molecules as languages and linkers as grammatical constructs, SyntaLinker transcends traditional heuristic approaches.

Read More Articles

Designing Better Sugar Stoppers: Engineering Selective α-Glucosidase Inhibitors via Fragment-Based Dynamic Chemistry

One of the most pressing challenges in anti-diabetic therapy is reducing the unpleasant and often debilitating gastrointestinal side effects that accompany α-amylase inhibition.