As of 23 June 2021, there are 14 variants of COVID-19 which are of concern or under investigation in the UK, according to the UK government. The unique profile of COVID-19 enables rapid mutation, producing variants which are more transmissible and deadly. Fortunately, the current vaccines against the virus remain effective, and on-going clinical trials investigate the efficacy of winter booster shots.

As a result of natural selection, viruses naturally mutate through errors in the viral genome. RNA viruses have much higher mutation rates in comparison with DNA viruses – mutations which do not interfere with the essential virus functions will persist in the viral population.

The rapid spread and transmission of COVID-19 globally has provided the virus with the opportunity for the natural selection of rare but favourable mutations which have enabled its survival. Although most viral mutations are benign, many mutations, such as D614G on the spike (S) protein, strengthen viral survival capability.

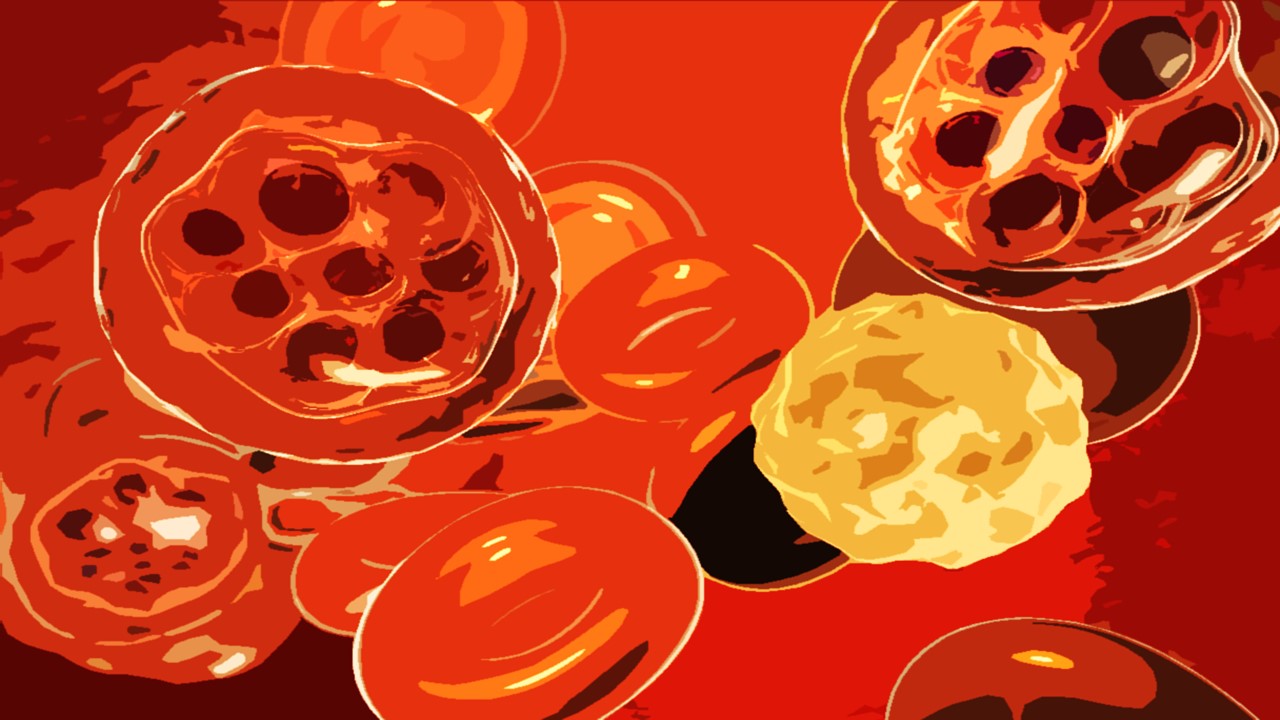

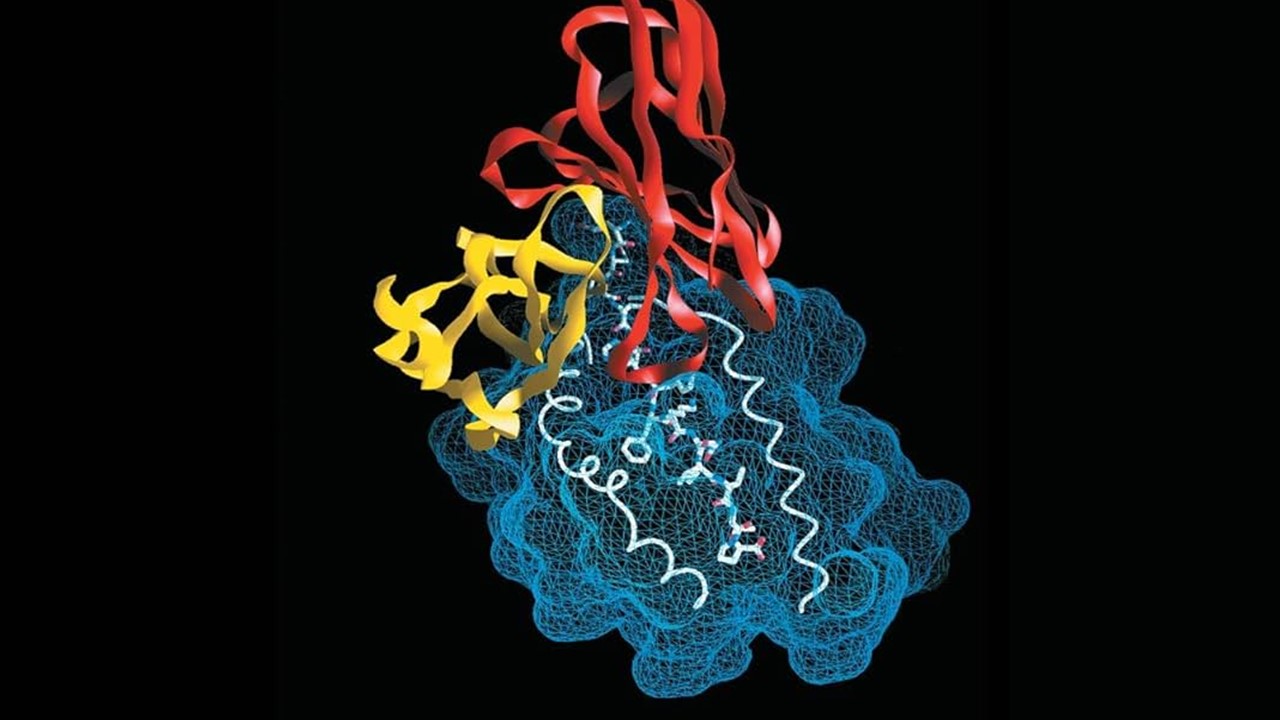

Coronavirus is a single-stranded RNA virus and contains one of the largest genomes for RNA viruses. Variants of COVID-19, a novel form of coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2, arise from genetic mutations which alter the spike (S) protein on the virus.

Since early January 2020, hundreds of new mutations were found on different residue positions of SARS-CoV-2 S protein. The S-protein is the key to infection within humans, as it mediates the binding of the virus to host cells which promotes entry and the later release of viral particles. The S protein is the main antigen component in all structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2. Antigens lie on the surface of viruses which trigger an immune response.

Mechanism of vaccines

Vaccines take advantage of the highly evolved human immune system, and essentially trick it into thinking it has detected a virus in order to promote the production of antibodies by B cells, specific to the antigen of interest.

The antibody level remains high in the body for up to two weeks after infection, which allows memory B cells to store copies of these antigens specific to the virus.

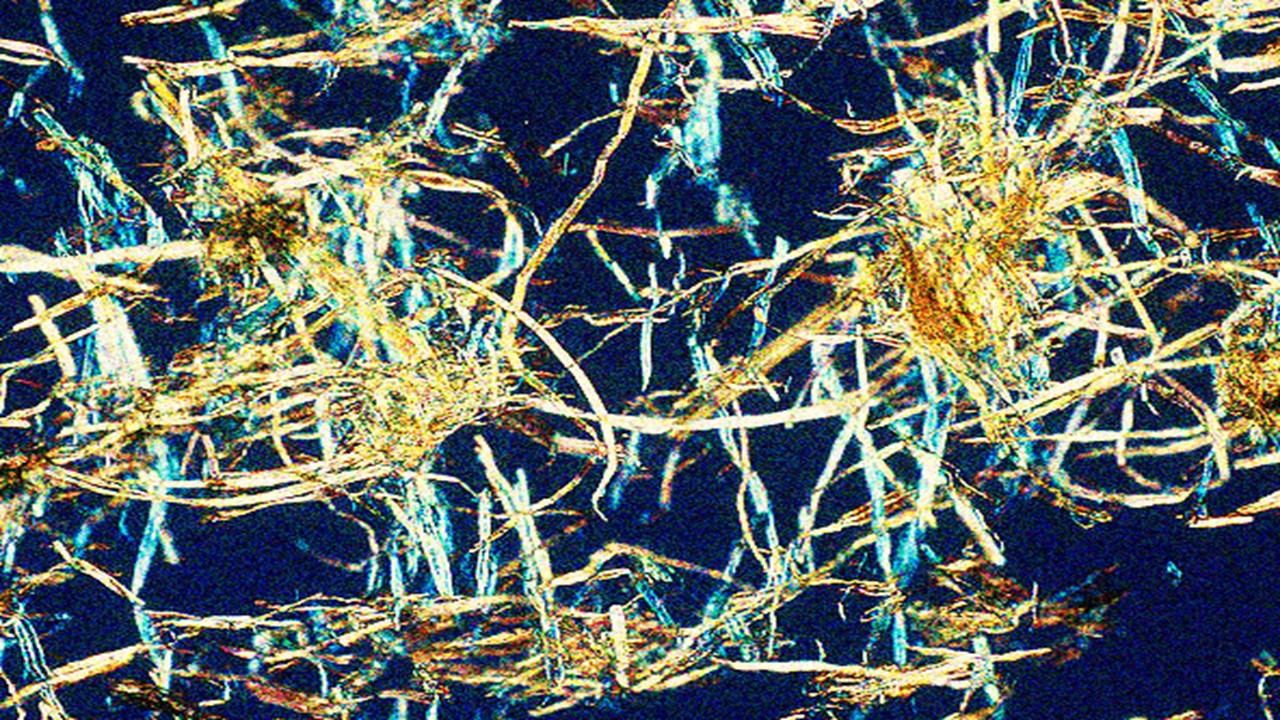

There are a number of COVID-19 vaccines that have been developed in the last year and include DNA- and RNA-based. RNA-based vaccines are derived from a molecule known as mRNA, which is the “intermediate step between the translation of protein-encoding DNA and the production of proteins”.

RNA vaccines initiate an immune response by introducing mRNA into the cells which have been engineered to carry the genetic instructions to produce the S protein. Through protein synthesis, the S protein is created which stimulates an immune response in the host and copies are stored by memory cells for future immunity should the body encounter the virus.

The many advantages to using RNA-based vaccines have been acknowledged for a number of years and are highlighted in a 2018 Nature article:

• mRNA-based vaccines are non-infectious

• mRNA is degraded by normal cellular processes, so there is no naked genetic code remaining in the host’s cells

• mRNAs possess an ‘inherent immunogenicity’. Immunogenicity refers to the ability of a foreign substance to induce an immune response. This “can be down-modulated to further increase the safety profile”

• Production of mRNA vaccines shows potential for rapid, inexpensive, and scalable manufacturing

This is a simplification of the mechanism for the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine.

In the development of the COVID-19 vaccine, it was important that the mRNA of the virus was modified. Unmodified viral mRNA is highly immunogenic and as a result can activate many pathogenic sensors which is a safety risk. In a 2021 study, it was emphasised that modified mRNA of the virus didn’t activate these sensors which was crucial to avoid excessive inflammation resulting in undesired side effects.

Vaccines against variants – the latest updates

As of today 16 June 2021, the current vaccines available, including AstraZeneca and Pfizer, continue to show protection from the Delta variant (B.1.617.2; formerly the ‘Indian’ variant).

Real world data from AstraZeneca shows a 92% effectiveness against hospitalisations due to the Delta variant (after a second dose). The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine has shown to be 88% effective against symptomatic disease from the B.1.617.2 variant two weeks after the second dose.

According to the government, however, both vaccines were only 33% effective against symptomatic disease from the Delta variant three weeks after the first dose, compared to around 50% effectiveness against the Alpha variant. With increasing numbers of people fully vaccinated, there is still a level of protection against the Delta variant for those with one dose thanks to herd immunity and the restrictions in place.

Boosters

The world-first COVID-19 vaccine booster study has recently launched in the UK, investigating the safety and efficacy of booster shots for COVID-19 protection in winter. According to the government, “the trial will look at seven different COVID-19 vaccines as potential boosters, given at least 10 to 12 weeks after a second dose as part of the ongoing vaccination programme. One booster will be provided to each volunteer and could be a different brand to the one they were originally vaccinated with.

Vaccines being trialled include Oxford/AstraZeneca, Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, Novavax, Valneva, Janssen and Curevac, as well as a control group”.

The COVID-19 booster shot will work in a similar fashion to the seasonal flu booster. Like COVID-19, the influenza virus has a tendency to mutate rapidly. Seasonal flu shots protect against the “three or four influenza viruses that research suggests may be most common during the upcoming season”.

The shots, which will be developed from the current vaccines, will ‘boost’ the immune system of those clinically vulnerable who naturally possess a weaker immune system.

A virus requires a host in order to survive and mutate, therefore, booster shots against COVID-19 in the winter will hopefully, and theoretically, reduce the prevalence of the virus in the population, minimising its chance to mutate further.

Charlotte Di Salvo, Lead Medical Writer

PharmaFeatures

Subscribe

to get our

LATEST NEWS

Related Posts

Infectious Diseases & Vaccinology

Harnessing IgA: A Breakthrough in HIV Vaccine Innovation

A vaccine eliciting strong IgA responses could revolutionize HIV prevention by protecting the virus’s primary entry points.

Infectious Diseases & Vaccinology

Prostate Cancer Precision-Targeting: The Promise and Challenges of Vaccine Therapies

The future of prostate cancer vaccines lies in combination therapies that harness the strengths of multiple modalities.

Read More Articles

Coprocessed for Compression: Reengineering Metformin Hydrochloride with Hydroxypropyl Cellulose via Coprecipitation for Direct Compression Enhancement

In manufacturing, minimizing granulation lines, drying tunnels, and multiple milling stages reduces equipment costs, process footprint, and energy consumption.

Aerogel Pharmaceutics Reimagined: How Chitosan-Based Aerogels and Hybrid Computational Models Are Reshaping Nasal Drug Delivery Systems

Simulating with precision and formulating with insight, the future of pharmacology becomes not just predictive but programmable, one cell at a time.

Decoding Molecular Libraries: Error-Resilient Sequencing Analysis and Multidimensional Pattern Recognition

tagFinder exemplifies the convergence of computational innovation and chemical biology, offering a robust framework to navigate the complexities of DNA-encoded science